This is one of the simplest things there is, once you’ve got the hang of it. ‘A child can do the laundry,’ they literally say in the Dutch language — which has nothing to do with current practices of child labour, by the way. Understanding the logic of Frisian personal names is essential if you want to have a seamless and non-violent hiking experience along the Frisia Coast Trail. Once you get it, a Frisian — or a Dutchman with Frisian roots for that matter — is also easily recognizable by both his or her first and last name.

Below, we will demonstrate that for example Sake Saakstra, from the hamlet of Saaksum, is a perfectly ordinary and respectable name in the northern coastal region of the Netherlands and, to a lesser extent, in the region of Ostfriesland in the far northwest of Germany — and, most importantly, not one to be ridiculed.

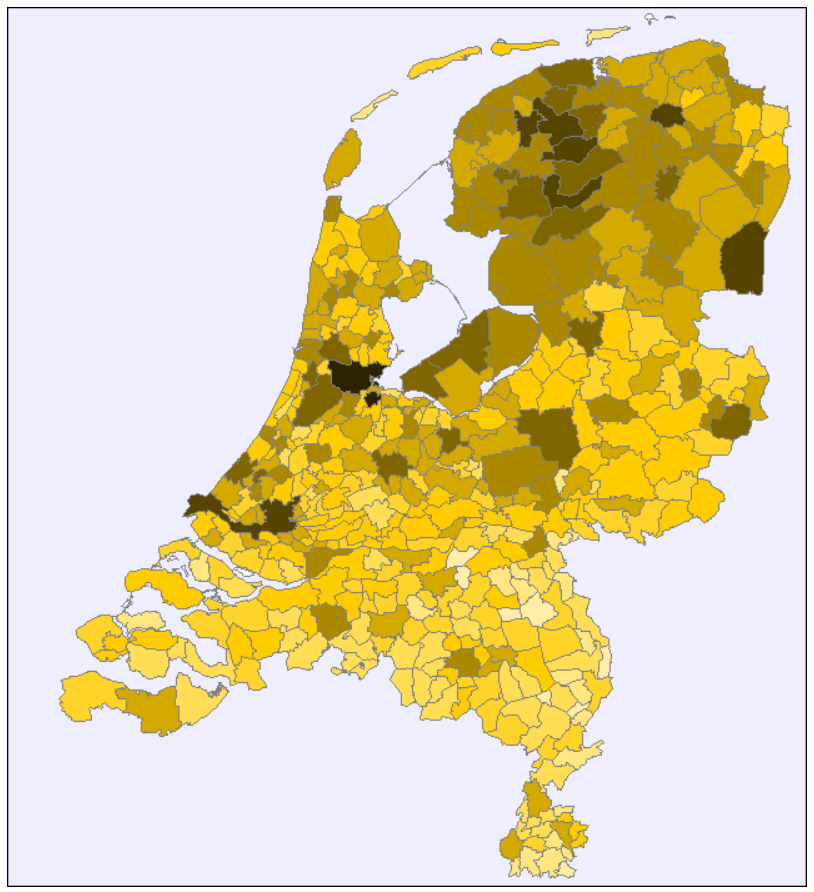

Do not shout it from the rooftops, but everything in this blog post applies just as well to the people of the province of Groningen — more precisely, to the region of Ommelanden (excluding the town of Groningen) east of the River Lauwers in the far northeast of the Netherlands.

Firstly, the first names

The variation and pliability of Frisian names is truly endless. Moreover, they are unpronounceable as well. Yes, the Frisian name-giving culture is actually very rich. You only need to think of the famous fashion model Doutzen Kroes, sounds like cow with the c replaced by d; dow-chún. Her name is the feminine version of Douwe, sounds like dow-wúh, which means ‘dove’. But also think of bizarre names like Djûke, sounds like ju-kúh. Say it quickly four times in a row and you think an express train is rushing by. Or Tsjitske, sounds like t-shit-skúh. Do not say it too loudly outside the province of Friesland, please. And Jitske, sounds like yeat-skúh. Or Sjoukje. Do not even bother to pronounce it.

The extension –ke normally indicates that it’s a feminine name. Not to enrage feminists, but –ke means ‘little’ or ‘small.’ Similar as in the Dutch language with the extension –je. This way, you can bend nearly every masculine name into a feminine name, and vice versa. For example, the author’s first name is Hans. He is actually named after his grandmother Hanske, thus ‘little-Hans’. For the name Hans, the author has always been extremely grateful to his parents. Besides its horrendous beauty, he is especially thankful for not having been named after his grandfather. The author’s younger brother has, however, and the poor man has to spell each syllable of his name to non-Frisians every day of his life, already for more than 45 years. His name is one of a kind, and giving it away here would mean we violate his privacy already.

But the –ke rule is not always applicable. Take, for example, the Frisian name of the well-known international Dutch actress Famke Janssen. If you leave out the –ke, you have not created a valid masculine first name with Fam. Quite the contrary. Famke means ‘girl’ in the Mid Frisian language, while faam is Mid Frisian for an unmarried young woman. Another example is the feminine name Nynke, sounds like neen-kúh. Like Faam, you will regret to have named your new-born son Nyn. Moreover, it sounds almost like The Nights Who Say “Ni!”.

Unless you follow the same dubious lazy strategy for raising your son as Johnny Cash described in A Boy Named Sue, it’s wiser to name him Popke instead of Poppe. Despite the diminutive -ke ending, this is a perfectly respectable and even cool masculine first name. In Mid Frisian, poppe namely means ‘infant.’ Even though Popke literally translates as ‘little infant’ — yet to the Frisian ear, it somehow still sounds strong and masculine. Alternatively, you might choose Fokke, pronounced a bit like fuck-kúh. Again, despite the -ke extension, it’s clearly a male name, with Fokje (fuck-yúh) as its feminine counterpart, suddenly using the Dutch –je extension. So, if you ever hear a Frisian shouting behind you, he might not be angry at you at all — just calling out to his wife, Fokje. Still with us? To add to the confusion, Joeke (you-kúh) can serve as both a male and female name.

One last twist: the same trick with –ke can also be done with –tsje, pronounced like chuh in church (just drop the -rch). For example: Wietze becomes Wietsje, or Sietze becomes Sietsje.

Anyway. The simple advice would be to consult a native of the north first before giving your new-born a name, if you are going to get creative and malleable with Frisian first names.

To get a little more feeling with the bizarre and exotic first names, some more examples for you to practice, selected from the three different sub-dialects of the Frisian language, that is Mid Frisian (Netherlands), North Frisian (Germany), and Saterland Frisian (Germany):

- Djurre (júr-rúh) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Durk (dúrk) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Ekke (ack-kúh) — North Frisian (m)

- Fardou (fart-dow) — Mid Frisian (f)

- Fiebe (fea-búh) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Fiebke (feab-kúh) — Mid Frisian (f)

- Fiede (fee-dúh) — North Frisian (m)

- Gatske (ghat-skúh) — Mid Frisian (f)

- Gosse (gozz-súh) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Iep (eap) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Jaldert (yall-dúrt) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Jaldertsje (yall-dúrt-chúh) — Mid Frisian (f)

- Jetske (yet-skúh) — Mid Frisian (f)

- Lian (lee-y-ne) — North Frisian (m & f)

- Lus (luzz) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Luske (luzz-kúh) — Mid Frisian (f)

- Oebele (oo-búh-lúh) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Oebeltsje (oo-bul-chúh) — Mid Frisian (f)

- Oedske (ood-skúh) — Mid Frisian (f)

- Riuch (r-yooch) — Saterland Frisian (m)

- Schoatse (shot-súh) — Saterland Frisian (m)

- Sikke (sick-kúh) — Mid Frisian (m)

- Tiadd (tea-yaught) — Saterland Frisian (m)

- Üüs (ues) — North Frisian (m)

One last piece of advice. Throw in an –e at the end of the first name. Mostly works. The Frisians love it. Just as the Zeeuwen or Zeelanders, that is, people from the province of Zeeland in the southwest of the Netherlands, love to do with their town and village names. For example the villages Aagtekerke, Gapinge, Krommenhoeke, Kwadendamme, Oudekerke, Ovezande, Veere, Werendijke, and Zoutelande.

Lastly, the last names

Now it becomes a bit more simple. So, hang in there for a while longer.

Any person with a surname in the Netherlands ending with –stra (whereby the a is pronounced as in aaarch; and do make a horrible face when pronouncing it), –ga or –(s)ma, is Frisian or has Frisian ancestors. The extensions –ga and –stra mean something like ‘from the area/place’. The extension –(s)ma means ‘the son of’. Do we have to explain to you what bitchma is?

It’s a bit like recognizing the Dutch and the Flemings with the prefix ‘Van’ such as Van Halen, Van Morrisen, Van Nuys, Vanderbilt, Van Nostrand, Van Sand, Van Zandt, Vans of the wall, Van Winkle, Van Cortlands, Van Buren, Van Diesel, Van Burnt, Van der Woodsen, Van Damme, Vanguard, Vans, Vann Harl, Van der Decken, Van der Linde, etc. Popular in Hollywood movies and with rock stars, celebrities, company brands alike. Although of origin a middle-name prefix, Van is also becoming more and more a first name in itself in the United States. At least, we guess the name Van is not referring to a motorized vehicle. Crazy too, these Americans. Similar to the name ‘Holland,’ which is not only a pretty common surname in the States, but can be a female first name, likewise.

Frisians can also transform first names into surnames by adding the –sma, –stra, or –ga, and vice versa. Turning surnames into first names by leaving out these extensions. To give you an example.

The male first name Sake (sounds like saaa-kúh). Adding –stra makes the perfect surname Saakstra, sounds like saaa-ck-straaa. If he comes from the hamlet of Saaksum in the province of Groningen then you would say Sake Saakstra from Saaksum, which sounds like saaa-kúh saaa-ck-straaa út saaaksum. No, this is not the Somali language. Trust us. The same can occur with Age Aggema from Aegum.

Vries, De Vries, and Fries

There is an additional complication with surnames, though. Next to Jansen, the most common surname in the Netherlands is ‘De Vries’ which literally means ‘the Frisian’. Both surnames have around 71,000 individuals that carry the name. This is curious since the Frisians only make up a miserable 3.8 percent of the total Dutch population of 17 million. Not very relevant, you might say. Rightly so. When the Dutch Republic was seized — without too much hassle by the way — by Mr megalomaniac Napoleon and incorporated into the France Empire, everyone who had no surname yet had to give or make up one. That was in the year 1811-1812. Most of them apparently called themselves ‘the Frisian’? Including many outside the province of Friesland. Big question mark.

But they cannot all have been Frisians. Unless the people of the provinces of Zeeland, Zuid Holland, and of Noord Holland were still aware that during much of the Middle Ages, their land was still known as Frisia — check out our blog post The United Frisian Emirates and Black Peat. How Holland Became Dutch to find more about the history of western Frisia. That would be building upon a very old tradition, by the way. It was after all Ubba the Frisian who led, together with the Viking warlords Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless, hordes of heathen warriors ransacking England in the ninth century. He and his warriors had the island of Walcheren in the province of Zeeland in the Netherlands as their stronghold and drinking hole — see our blog post Walcheren Island. Once the Sodom and Gomorrah of the North Sea.

A similar state of confusion we experience with the surname Fries (pronounced as freeze). Fries is a common name in Germany and Switzerland. To ease our mental situation, we dedicated an entire blog post to the surname Fries to explain its history. Check From Patriot to Insurgent: John Fries and the First Tax Rebellions and A Severe Case of Inattentional Blindness: The Frisian Tribe’s Name.

We are side tracking. Point is, we are available for suggestions on the ‘De Vries’ name-giving matter.

By the way, even in the south of France people carry the (first!) name Jean-Fris or Frisa meaning ‘the Frisian’. The story behind it, is the Frisian warrior-saint named Saint Fris, and who is being venerated in several villages in southern France to this very day. See our blog post Like Father, Unlike Son — Un Saint Frison en France for more about this fascinating bit of French history, or apocrypha.

Conclusion

All the foregoing is very normal for the people of the north living along the Wadden Sea coasts. The name-giving culture of the Frisians is as fluid as their water-rich land. So, do not start to smile or worse, when one presents himself with: “my name is Gjalt Gjaltema (or Gjalt Gjaltsma), Juw Juwsma, Fokje Fokkema, Eise Eisinga, Riemer or Rimmer Riemersma, Herre Herrema, Gosse Goslinga, Eelke (Jelles) Eelkema, Tjitske Tjitsma, Sjoerd (Wiemer) Sjoerdsma, Hoyte van Hoytema, Jitske Jitsema, Aukje Aukema, Gale Galema, or Popke Popkema.” No, do not blink an eye! Otherwise hiking the Frisia Coast Trail turns out not only to be hell for just your legs and feet.

Note 1 — April 2024, the Bundestag (‘parliament’) in Germany adopted a law that restores the Frisian name-giving tradition — friesische Namenrecht. This means that after two centuries Frisians in Germany have the possibility again to derive their Nachname (‘surname’) from the first name of one of the parents. For example Ose, the daughter of Yfke and Tamme, can be named either Ose Yfkes or Ose Tammes. Or their son Hajo can be named either Hajo Yfkes or Hajo Tammes. Criterium for who is Frisian is ‘everyone who feels himself Frisian’. Great!

This tradition also existed in the Netherlands with names like Jan Cornelisz. or Cornelis Jansz. The z is an abbreviation of zoon meaning ‘son’. Therefore, Jan Cornelis (his) son and Cornelis Jan (his) son, respectively. Jan is Dutch equivalent of John. Modern Dutch last names ending with -s or -sen are a reminder of this tradition. Tip to our ancestors would have been not to name your sons after yourself, like Jan Jansz. because it limits the richness of the name-giving. You are caught in a circle. Perhaps explaining why the last name Jansen and Johnson, is so common.

Concerning the first names in the region of Ostfriesland, the tradition is as rich as in the province of Friesland. Some examples with first the male version followed by the female one: Tammo—Taalke; Lübbo—Leentje; Reemt—Rixte; Onno—Okka; Meeno—Maaike; Ubbo—Umma; Gralf—Geesa.

Note 2 — One of Flanders’ most illustrious counts was Robrecht de Fries (1029/32–1093). He earned the epithet “the Frisian” through his close ties with the County of West Frisia. Robrecht married Gertrude of Saxony, the widow of the count of West Frisia, and served as regent for his stepson, Count Dirk (Durk) V (1052–1091). West Frisia would later evolve into the Province of Holland and West-Friesland, forming the centre of power of the Dutch Republic in the early modern period.

Yet another historic figure was Rainers lo Frison, also written as lo Frizos and meaning ‘the Frisian’ too. He was a crusader in the thirteenth century and functioned as the sword of the Roman Catholic Church to slay the heretic Cathars. Better be proud of it…

Note 3 — If you would like to give your child an authentically ancient Frisian name, here is a selection of names recorded in runic inscriptions (specifically Anglo-Frisian runes), dating from the sixth to the ninth century: ᚢᚱᚫ (Uræ), ᚪᛁᛒ (Aib), ᚻᚪᛒᚢᚳᚢ (Habuku), ᚻᚪᛞᚪ (Hada), ᚫᛈᚪ (Æpa), ᚹᛖᛚᚪᛞᚢ (Weladu), ᛋᛣᚪᚾᛟᛗᛟᛞᚢ (Skanomodu), ᚪᛞᚢᛡIᛋᛚᚢ (Adujislu), ᛡIᛋᚢᚻIᛞᚢ (Jisuhidu), ᚹIᛗᛟᛥ (Wimœd), ᛏᚢᛞᚪ (Tuda), ᚫᚻᚫ (Æhæ), and ᚩᚳᚪ (Oka) (Looijenga 2003).

To turn a personal name into a family name, you can add one of the three characteristic Frisian suffixes — -ga, -ma, or -sma — represented respectively in runes as -ᚷᚪ, -ᛗᚪ, and -ᛋᛗᚪ 😉

For many more ancient Frisian names, see our blog post A Collection of Frisian Forenames of the First Millennium.

Suggested music

- Johnny Cash, A Boy Named Sue (1969)

Hello! Do you know anything about the frisian name Foske for a girl? Do you know what it means? Thank you. Susan Olson

LikeLike

Fos, Foske, Fuskje is a Frisian name form, indeed. It’s a strongly reduced form of Germanic names beginning with ‘folk-‘ (also folc, volk, volc) meaning ‘people of war’ (Van der Schaar 1964). Bit meager, I know!

LikeLike

Any info on the surname Finke?

LikeLike

(1st) One explanation might be that it is the same as the bird species vink (‘finch’). (2nd) Another explanation is that it is a diminutive of the name Fen, Fenne, Fenna, Fenny etc. A Germanic name with the first component ‘fred(e)’ in it, meaning ‘protection/safe/secure’. The second component started with an ‘n’ like Ferdinand. (3rd) Yet another option is that it derives from Finniko which would be a Germanic tribes name. Sources: Meertens Knaw Institute (website); Schaar, van der J., Woordenboek van voornamen (1964)

LikeLike

Thank you. My father’s German sounded different from my mother’s, whose family came from Pommern in Northeast Germany. He referred to himself as “Pennsylvania Dutch” which could have been an alternate pronunciation of Deutsch.

LikeLike

R.E.H.

On our cemetery in Jubbega I’ll find names like Himme and Bokje. The first is male the latter female.

I’m called Popke, my mother was called Janke. A nearby neighbor is called Jippe,

A village nearby I knew a bakers wife called Bjoikje of Bjeuikje, I don’t even know how to write that.

Do you have some info or the right spelling on the last name and about the names I found on the cemetery. Still a lot of Frisians names going around, but nowadays youth is forced out of Frisian and incorporated into the Hollandic Dutch dialect. The schools don’t allow Frisians speaking their own language. There is almost not a Frisians speaking child left. Parents are manipulated to consent and within a 30-40 all will be gone just like in other areas. It’s severe supressed on school and the children even speak Hollandic Dutch to their parents. They are very strong pressed to do so from schools. Else they will be branded anti-social by their Hollandic-Dutch teachers. There is fear to speak their own language so they drop it because of the consequences. So Frisian names on ‘our’ children are strongly in decline because of the ‘ver-hollandisering’ of Frisia.

LikeLike

My family name is Finke. When my father spoke German, it sounded more like Dutch. He called himself “Pennsylvania Dutch” which may have been a mispronunciation of Deutsch. Any help on whether my ancestors were Frisian?

LikeLike

Bit more about the Pennsylvanian Dutch: https://frisiacoasttrail.blog/2022/07/27/from-patriot-to-insurgent-john-fries-and-the-tax-rebellions/

LikeLike

Bjoke is a Frisian name, variation of Bokke. Might be how the name of the bakers wife.

LikeLike

How about the origin of the name Epke? I’ve searched for this etymology a couple times but I don’t speak dutch or frisian in order to delve as deep as is apparently necessary for an ordinary american to figure it out.

I guess it must be another one of the exceptions to the rule about the -ke suffix indicating femininity?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Epke probably is a hypocorism (viz. pet name) of so-called ‘ever’ names. An ‘everzwijn’ or ‘ever’ is a wild boar. This animal represented strength and courage. Germanic names generally consisted of two parts. Perhaps from Everhard/Eberhard with the part ‘hard’ meaning strong, so ‘strong wild boar’. But, as said, shortened to Ep or Eb(be) and Epke. And, indeed, another exception!

LikeLike

Excellent, thanks

LikeLike

Both my maternal grandparents were born in Wilhelmshaven, circa 1900, and were also both part Frisian. Tonight I was reexaming the records for some Frisian ancestors. I have a (Weiland) Pepke Janssen who had a daughter, Elisabeth. She married a Johann Hinrich Moulin… a descendant of a 17th century Pastor who came to Wittmund, East Frisia. Elisabeth and Johann Hinrich named their son Poppe Moulin (sometimes Molien). Yike! My question… does Pepke actually mean something like little Peter? Also, is Cassen the Frisian equivalent of Christian? I have loads of ancestors with old Frisian names, many ending in -ke. However, the chosen names of their descendants became more mainstream after the 19th century arrived.

LikeLike

We tried to figure it out for you, but found no really conclusive explanation. For sure, Pepke (or Popke) has nothing to do with the name Peter. According to Van der Schaar (1964) the name Poppe is pet name variant of Germanic names with the stem ‘folk’ meaning ‘armed men/people of war’ (according to Meertens Institute). Poppe, Popke, etc. in so-called children language is shaped through the use of bilabialization, which means that during sound pronunciation both lips are brought together to stop the incoming wave of air stream, like in the words pie, coping, clubbing, etc. We could, however, not find a satisfying explanation how the component ‘folk’ is shaped through bilabialization into the name Poppe.

LikeLike

Thanks—very informative-Bouke H——-sma

LikeLike