The heart of Western democracies is the joint assembly of Parliament, Cabinet, and High Councils of State. Its Celtic-Germanic origin is the thing, also called ting, ding, ðing, or þing in other writings. Today, national assemblies in Scandinavian countries still refer to this ancient tradition. For example, the parliaments of the Faroes Løgting, of Greenland Landsting, of Iceland Alþingi, and of Norway Storting. However, the oldest written attestation of the thing institution comes from a band of Frisian mercenaries in the Roman Imperial Army deployed in Britannia. This was in the third century AD. So, almost 2,000 years ago! Thanks to them, we know that North-Western political arenas can boast of an old and quite successful tradition.

The thing is, however, criticism of our modern assemblies and their effectiveness in representative consensus-building is growing. According to the THING project, an international cooperation funded by, among others, the European Union, the story of the thing is a reminder of an age-old need for robust legal systems and open debate. And a reminder of the importance of trying to resolve conflicts without resorting to violence. Especially relevant at a time of increasing internationalization and globalization.

In line with this plea, at the end of this blog post, we’ll formulate five advices for the thing of today: how to strengthen its function and performance in our democracies, how politics and bureaucrats can reconnect with civilians and social issues, and how to create a new administrative culture.

But before we do that and look at the future of the contemporary thing, we first take a look back. Something politicians who are in power are often not too eager to do (if not, please scrol to the end at least). When looking back, we understandably, and with good reason, do this with a special interest concerning early-medieval Frisia.

1. The Matter of Things

1.1. Frisians introducing the thing

The Romans, when arriving in the northwest of continental Europe around the beginning of the common era, described how the tribes of this area governed themselves. Roman historian Tacitus documented how the assemblies functioned, especially in the central river area of the Netherlands. In his book Historiae, dated 100-110, Tacitus described the uprising of the Batavii in the year 69. A people living in the central river area of the Netherlands. Their leader Julius Civilis gathered the nobles and the most fierce men of his people in a sacred wood.

When he saw that darkness and merriment had inflamed their hearts, he [Julius Civilis] addressed them. Starting with a reference to the glory and renown of their nation, he went on to catalogue the wrongs, the depredations and all the other woes of slavery. The alliance, he said, was no longer observed on the old terms: they were treated as chattels. (…) He received wide support for his words. Barbaric rites and ancestral oaths followed which bounded everyone together.

Historiae, Tacitus

By the way, the Cananefates, a tribe that lived in the area of the current city of The Hague, and the Frisians from north of the River Rhine, joined this uprising against the Romans. The Frisians attacked the fortresses of the limes along the River Rhine with a naval fleet. A band of Frisians and Chauci operated during the uprising even high upstream the River Rhine, at the town of Tolbiacum. Where the current town of Zülpich in Germany is today, not far from the city of Bonn. At Tolbiacum the Frisian and Chauci warriors were defeated in a remarkable way. The people of Tolbiacum had offered the warriors a banquet with a lot of wine. After the Chauci and Frisians had fallen asleep drunk, the doors were closed and the building set afire.

Concerning the thing Tacitus also wrote:

On matters of minor importance only the chiefs deliberate, on major affairs, the whole community; but, even where the commons have the decision, the case is carefully considered in advance by the chiefs. Except in case of accident or emergency they assembly on fixed days (…) When the mass so decide, they take their seats fully armed. Silence is then demanded by the priests, who on that occasion have also the power to enforce obedience. Then such hearing is given to the king or chief, as age, rank, military distinction or eloquence can secure; but is rather their prestige as counsellors than their authority that tells. If a proposal displeases them, the people roar out their dissent; if they approve, they clash their spears. No form of approval can carry more honour than praise expressed by arms.

Germania, Tacitus

Tacitus didn’t mention, or didn’t know, the name of the assembly of the Germanic tribes. He used the Roman word concilium. Luckily, as said in the introduction of this post, Frisians did preserve its name for us. In the third century, namely, an auxiliary unit of the Roman Army with Frisian mercenaries deployed at Hadrian’s Wall in Britannia near modern Housesteads, erected a stone pillar and wrote the following, legendary words (De Kort et al. 2023):

DEO MARTI THINCSO ET DUABUS ALAISIAGIS BEDE ET FIMMILENE ET N AUG GERM CIVES TUIHANTI VSLM

“to the god Mars Thincsus and the two Alaisiagae, Beda and Fimmilena, and to the Divinity of the Emperor the Germanics, being tribesmen of Tuihanti, willingly and deservedly fulfilled their vow”

The name Tuihanti refers to the current region of Twente in the eastern parts of the Netherlands. However, these Tuihanti tribesmen have been interpreted by historians as Frisians (Nijdam 2021). An altar stone erected by the cunei frisiorum and pottery of Frisian material culture at Housesteads point to this. Furthermore, Deo Mars Thincsus means ‘god Mars of the Thing‘. Mars of the Thing must be interpreted as Tîwas of the Thing . It was the god that decided over war, embodied law and order, and was the protector of the thing. Much in common therefore with the gods Dios, Zeus and Theus (Schuyf 2019). The god Tîwas, also named Tîwes or Tiwaz, is the same as the god Tuw. This was, in early Germanic times, a supreme idol. In Scandinavia it was known as Tyr. The rune ᛏ of the early-medieval Anglo-Frisian futhorc alphabet is called tir after the god, also meaning ‘glory’ in Old English.

Might the fact that in the province of Friesland relatively many small statues of the god Mars have been found when compared to the rest of the Netherlands, respectively eight and six, be linked with the importance of the thing in Frisian society? (Visser 2023)

The names of the two idols Beda and Fimmilena of the same pillar inscription at fort Housesteads refer to bodthing and fimelthing, both of which are also recorded in medieval Old Frisian codices (law books) from around 1100 onward. Indeed, a stunning nine centuries later. These were specific types of assemblies. Perhaps the distinction was: the ‘fixed thing’ was protected by the god Thincsus, the ‘extraordinary thing’ was protected by the god Beda, and the ‘informative or non decision-making thing’ was protected by the god Fimmilena (Iversen 2013).

It’s interesting to note this pillar therefore not only testifies of Frisian presence in Roman Britain, but also happens to be the oldest written evidence of the (word) thing. Hear! Hear! Something in the pocket of the obscure Frisians. Indeed, such democratic dudes those Frisian mercenary soldiers. Moreover, we plead, time for peripheral Frisia to join the THING project too. In addition it makes us curious whether these thing-worshiping soldiers at the frontier ever reached consensus before going into battle, and whether that was the true historic reason why at the end Hadrian’s Wall didn’t hold against the wild Scots 😉 For more background on the soldiers of fortune, turn to our post Frisian Mercenaries in the Roman Army.

The Old Germanic form of the word ‘thing’ is þingsō which derives from the word þengaz and translates to ‘certain time’. In Gothic it’s þeihs meaning ‘time’. It was therefore a specific fixed time on the lunar calendar the people gathered, and that’s how the word thing received the meaning of folkmoot and assembly, and of justice. Indeed, the right time – besides the right place – was of the very essence for the thing assembly (Sanmark 2017). In the German and Dutch languages the day of the week Tuesday is called after the thing, namely Dienstag and dinsdag, In other words, thing-day.

In Dutch speech the expressions in geding zijn ‘being inside the thing / being disputed’, een geding aanspannen ‘filing a thing / a lawsuit’, and who knows even the popular informal expression dit wordt een ding/dingetje ‘this will become a small thing/ an issue’, are all being used in daily life to this date. A dading is a legal agreement between parties to end a conflict in Belgium law, and is another trace in modern Dutch language. On the border of Belgium and the Netherlands, the Dinghuis ‘thing-house’ is a former late-medieval courthouse in the city of Maastricht. Unlike in the German and Dutch languages, the English, Frisian and Scandinavian languages refer with respectively Tuesday (Old English Tíwes dæg), tiisdei and ti(r)sdag, to the patron god of the thing being Tiwas or Tyr.

Besides Tacitus‘ record, we haven’t much information on how the thing functioned during the Roman period. The origin of folksgearkomsten (in Mid-Frisian language) or Volksversammlungen (in German language) ‘assemblies’ might be in the Late Iron Age, a period of major social transformation. Check our post It all began with piracy in which we explain how this social transformation process went, and how important large-scale sea raiding was part of it. It’s in this early period that in the central river area of the Netherlands, indeed the area of the Batavian uprising mentioned by Tacitus earlier, regional cult places emerge, indicating the manifestation of ethnic groups. Archaeological research at Empel and Elst, and very recently at Tiel, in Central Netherlands has proven ritual feasting at these cult places. These were sanctuaries where the community gathered in public space, and where the members of the community took part in a fundamental activity for the social and biological reproduction of the group (Fernández & Roymans 2015). From this development the thing evolved. Also explaining why thing sites, or Dinghügeln in the German language, regularly can be found at ancient cult sites.

As said, a very recent (2017) and impressive addition to these cult sites in the central river area is the massive shrine near the town of Tiel. It’s a grave mound solar calendar and estimated a 4,000 years old, and already dubbed as ‘Stonehenge of the Netherlands’. The largest mound was 20 meters in diameter (Neijens 2023).

1.2. The medieval thing

From the Early Middle Ages we do know a bit more about the functioning of the thing, thanks to the first law codices of Germanic societies were being written by then. The medieval thing was an assembly during which delegates, mostly so-called freemen, from the concerning area discussed legal, military, political and religious matters. In this way, the thing fulfilled an important role in conflict resolution, and in avoiding long-term feuds and wars (Sanmark 2009).

The thing site could be a dangerous place as well. A central place of gift-giving, where authority was either consolidated or challenged (Tys 2018). Indeed, a political arena. To maintain order during the thing gathering, a so-called peace, in the Old Frisian language called a frede, was proclaimed. The modern Mid-Frisian word for peace is still frede. A thing site was considered a sacred place where all participants were equal. When someone committed a kill during a frede or thing assembly, penalties were significantly higher (Sanmark 2009). From the high-medieval Upstalsboom thing assemblies in East Frisia, we know that the same heavier punishments were also applicable when you harmed or killed a delegate on his way to the thing; see our post You killed a man? That’ll be 1 weregeld, please and Upstalsboom: why solidarity is not the core of a collective for more about penalties and the (thing) peace. In medieval Scandinavia, the practice was about the same. Here a thing peace was called a griðr or friðr (Sanmark 2017).

The class of freemen, although there were regional variations as to who were allowed to participate in the thing and who were not, belonged to the higher social class of Germanic society. We may assume that the social class of nobiles participated as well and had the right to vote, and that of the serfs or thralls obviously not. Furthermore, women were in principle not allowed either. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, since it took modern democracies only until recently to give women the right to be elected for parliament. There are indications, however, that prior to Christianization women, as a modest share, did participate and vote during thing meetings, especially if they were landowners themselves (Sanmark 2017). Freemen weren’t only allowed but also obligated to participate in the thing.

Maybe, in today’s world we can compare the freemen with the elite of regents at first, and later with the elite of politicians. When you come to think of it, the British House of Lords and, to a lesser extent, the Dutch Senate still have features of grey, distinguished-looking freemen at the thing. Admittedly, less warrior-like.

Of course, Montesquieu would turn over in his grave for sure if he would hear of the thing combining all government functions at the same time. Functions like administering justice, making laws and even executing them too. The fact that combining the judicial, legislative and executive powers was possible for the Germanic peoples, was because they regarded the thing, its time and place, as something sacred, and therefore considered checks and balances through separation of powers not necessary (Corthals 2014). The personal conviction of statesman and Grand Pensionary of Holland, Johan de Witt, in the never-ending gathering and commonwealth through consensus during the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century (Panhuysen 2005), might in a way mirror this old cultural tradition of this region.

Decision making at the thing was (1) under oath, as we still do, (2) took place in open-air and was witnessed by the public, as we partly still do, and (3) was approved by the ancestors and the gods. It was sacred. Dutch laws are still being signed with the phrase ’by the Grace of God’. Members of parliaments of many countries take an oath or a solemn affirmation, to this day.

Notwithstanding the sacral status, the thing was often located at boundaries between districts, and at some distance from residences of lawmen and local big men (Sanmark 2009). This to guarantee the neutrality of the thing. With the introduction of feudalism, thing sites regularly were (re)located near residences of the (local) powerful men, or vice versa. No longer these assembly sites were neutral but a way to exercise royal, feudal control over the gatherings.

However, in Mid Frisia and East Frisia, which encompassed the coastal zone of northern Netherlands and of northwest Germany, feudalism completely crumbled during the High Middle Ages, and the thing continued to function without (central) rulers until more or less the end of the fifteenth century. Quite or very unique in Western history. The thing, part of a formal legal feud and honour society which Frisia continued to be until the early modern period, remained the arena for law making, court ruling, political affairs etc., all this time. Whereas in Scandinavia, on most of the Continent, and on the British Isles, feudal structures grew and turned into centrally-led states where power concentrated with the few. Where the thing became subordinate to kings. In other words, besides Frisians can claim the oldest mention of the thing, they can also claim the longest continuation of the thing functioning as a classic folkmoot. People governing themselves. A period stretching from more or less the first century AD until around the year 1500.

The spot of the assembly itself also amplified the sacral nature. Often the thing was located near water, and often on a natural slope, mound or at a pre-Christian cult site. Also, the concept of a thing being a mound as an actual or symbolic island surrounded by water, stressed the sacred nature (Sanmark 2017). Research into mound toponyms in Britain showed that the Old Norse haugr predominates in the Danelaw region, the Old English toponym hlāw is common in the Midlands, and the Old English beorg is specific for thing sites in southern England (Tudor Skinner & Semple 2016). In the Netherlands the elements beorg or berg can also be found in the toponyms Sommeltjesberg and Schepelenberg, which are thought to have been thing sites (see further below).

Near Dunum in the region of Ostfriesland the toponym Rabbelsberg or Radbodsberg ‘Radbod’s mound’ exists. Who knows this might refer to an old thing site as well. This handmade hill, or tumulus, is as old as 4,000 years. According to an East-Frisian saga, mound Rabbelsberg and nearby loch Hünensloot were created after a domestic fight of giants. The wife brought her husband food out on the field, but he didn’t like it and got angry. The giant threw the pot away. At the spot where the pot hit the ground, a loch and mound were created. Later, the mound supposedly became the burial mound of King Radbod of Frisia.

Some Scandinavian thing sites simply carry a mythical or magical atmosphere, like those of Gulating in Norway, Þingvellir (‘assembly plains’) on Iceland, and Tingwal on Orkney. Stressing the sacred proceedings at the thing. The thing site itself was often enclosed. This could be an enclosure shaped by natural boundaries, whether or not completed with handmade earthen structures. The thing site could also be marked by stringing a rope or a fence.

In early-medieval the Netherlands, the spot in open air where justice was being dispensed, was encircled with cords too. In the city of Amsterdam in the early modern period, this area was called De Vierschaar ‘the four part’, referring to the four benches placed in a square where the sworn men were seated to administer justice. Later, after justice was being done inside the town hall, the room was still named De Vierschaar and still accessible to the public through open windows facing the street, i.e. Dam square (Thuijs 2020).

The thing always took place on Tuesdays under a new moon or full moon. Contrary to today, the thing only gathered a few times a year. Furthermore, the thing was moderated by a law-speaker or, later, a priest. Law-speakers were wise men capable of memorizing and reciting the laws (Ahlness 2020). Tasks of the law-speakers during the thing were: guiding the ruling in legal disputes, the administration and the execution of decisions, and to speak on behalf of peoples and communities. The law-speaker developed in Scandinavia into the office of lagmän (Finland), lagmann (Norway), laghman (Denmark), and løgmaður (Faroes). Of course, the United Kingdom still has a Speaker of the House of Commons. In the Netherlands’ parliament, the speaker is called voorzitter, which is a word related to the medieval Frisian god Fo(r)seti, meaning presiding. The office of the president of Iceland is named Forseti Íslands. Forseti was a son of the righteous god Baldr and the god of law and justice. The Germanic variant of the idol Maät of the ancient Egyptians but for the living, so to say. Forseti was being worshipped by the Frisians on the island Heligoland at the North Sea (see further below).

The Woolsack – Another speaker, the Lord Speaker of the House of Lords of the United Kingdom, sits on a red sack of wool, the Woolsack. It is a testimony of how important wool has been for the country between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. England, Scotland, and Wales had become the producers of wool in Europe, and their elite earned dazzling amounts of money with it. Today, the sack contains wool from all parts of Britain and the Commonwealth. “Ecclesia, foemina, lana” (‘churches, women, wool’) were the three miracles of England (Joseph Hall, 1574-1656). Read our posts Come to the rescue The Rolling Sheep and Haute couture from the salt marshes to understand the importance of sheep and wool in the North Sea region.

In medieval Frisia, the law-speaker was called asega. The component a means ‘law’ and the component sega means ‘to say’. In the late eighth-century Lex Frisionum ‘law of the Frisians’, reference is made to this office, called iudex or sapientes (Nijdam 2021). The asega isn’t in any way a judge but an authority of law. An expert of justice and of proceedings during the thing. The Fivelgoer Handschrift ‘Fivelgo manuscript’, dated circa 1450, contains the so-called Asega Law. These are the standard formulas how the thing gathering commenced, written in the Old Frisian language. The first formula for the thing to start, a dialogue between the asega and the skelta ‘ judge’, sounded as follows:

Asega, ist thingtid? Alsa hit is.

Asega, hot age wi to dwane in thisse nie iera?

I agen frehe to bonnane […]. Thet agen tha liude to loviane and I agen iuwe bon theron to ledzane.

Law-speaker, is it thing time? So it is. Law-speaker, what do we have to do in this new year? You must pronounce peace […]. The people must vow to this and you must proclaim your ban on it.

Interestingly, according to Old Frisian codices, Widukin(d) was the first asega of the Frisians (Vries 2007). Widukind was the late eighth-century leader of the Saxons who revolted against the Franks. This uprising was joined by the neighbouring Frisians.

At the village of Bernsterburen in the province of Friesland a whalebone staff with a T-shaped handle was found by a Mennonite minister in the year 1881. It is dated around 800 and pretty unique, because it’s the only artifact known of this type in and outside the Netherlands. The runic inscription ᛏᚢᛞᚪ ᚫᛚ ᚢᛞᚢᚴI(?)ᛌᚦᚢ ᛏᚢᛞᚪ says: “tuda æwudu (or æludu) kius þu tuda“. Translated this could be ‘Tuda, witness(es) choose you, Tuda’, or ‘Tuda, witness(es) he made, Tuda’. De personal name Tuda stems from Germanic word þeuð meaning ‘people’. So, if it is not a personal name, it might also address the gathered people at the thing. Therefore, one of the theories is that the staff is a ritual attribute of law speaking. Maybe used by the asega during the thing (Knol & Looijenga 1990, Looijenga 2003, IJssennagger 2012, Looijenga 2023).

Another intriguing artifact is the wooden miniature sword excavated at the village of Arum in the province of Friesland too, dated eighth century. It carries the runic inscription ᛗᛞᚫ ᛒᚩᛞᚪ to be pronounced as ‘edæ boda,’ meaning something like ‘oath messenger’ (Looijenga 2003). Earlier in this blog post, we discussed the bodthing, ‘commanded thing.’ Therefore, we offer another translation, namely ‘oath commanded.’ In the Dutch language still pretty recognisable, namely: geboden eed. We like to imagine that the delegates of the thing had to make an oath on this wooden sword, and the sword lay visibly for everyone in the circle, because real weapons were not allowed at the meetings. Contrary to Looijenga, other scholars argue the inscription cannot be read as an oath since the Old Frisian word for that would have been eth and not edæ (Nijdam, Spiekhout & Van Dijk 2023).

Interestingly, another (piece of a) miniature sword, this time made of whale bone, with two runic inscriptions and found in former Frisia too, has been preserved, namely that of the terp village of Rasquert in the province of Groningen. One inscription is too eroded to be read. The other inscription Mᚳᚢᛗᚨᛞᚳᛚᚩᚳᚪ reads ekumæðkloka (ek, Umæ ð(i)k loka) which translates as `me Umæ [personal name] write in you’ (Buma 1966). Other say the inscriptions reads edumæditoka but do not know what it means (Nijdam, Spiekhout & Van Dijk 2023).

Besides the asega, the frana played an important part during the thing gatherings. The frana was the substitute of the count or the schout (i.e. local official tasked with administration and law-enforcement) during the high-medieval period when Frisia was governed through the feudal system, and presided the thing. Later, during the Late Middle Ages when Frisia no longer was governed by feudal lords and all state structures had crumbled, the office of the frana was replaced by the grietman. The republican office of grietman, which was an elected local judge annex governor, rotated each year (Nijdam 2022).

Before the sixth century, in the regions of Austrasia (i.e. Frankish kingdom), Frisia and Saxony, there existed three levels of assembly. These were: (1) the centena, also called herað or hundred, (2) the pagus, also called þriðjungr or fjórðungr, and (3) the civitas, also called fylki. Between the tenth and twelfth centuries, similar tripartite systems are found in Scandinavia and Iceland of which we have already mentioned the names above (Iversen 2013). The level of the centena was the lowest level of the thing. The mid-level was that of the pagus, in Germanic speech called gau. In the province of Friesland gau evolved into go, and to this day the Dutch speak of gauw. With the emergence of the big European kingdoms, the pagi and its thing transformed into comitati, i.e. shires and counties. The highest level of the thing was that of the civitas.

As is the case in Scandinavia, locating thing sites in the territory of former Frisia is troublesome too. The thing was an occasional, short open-air venue, with probably only temporarily shelters for the participants, like huts and tents. As a consequence, the thing almost left no traces in the soil to be found through archaeological research today. Nevertheless, a few thing sites have been located and excavated, like the ones on Greenland and Iceland (Sanmark 2009). Thing sites in these countries had more solid ‘shelter facilities’ recognizable for archaeologists, because travel distances for participants to the thing might have been greater and the weather harsher. For historians too it’s difficult to get a firm grip, since historical sources almost make no reference to thing assemblies, let alone that old texts give away the coordinates. Besides archaeology, some thing sites can be assumed based on toponyms, like evidently with the components ding, ting or, in Middle-Dutch speech, dijs. Might Tating on the peninsula Eiderstedt in the region of Nordfriesland in Germany be a thing site too?

centena thing

In the case of Frisia, there’s almost nothing known about the thing at the centena ‘hundred’ level, also called hundred organisation. For West Frisia, the coastal zone from, let’s say, the town of Knokke-Heist in Flanders to the island Texel in the province of Noord Holland, it might be possible these local things were combined with the early-medieval cogge districts, and thus the institute of the heercogge ‘war-cog’. The heercogge or herekoge was a kind of conscription for the inhabitants of a cogge district, who had the obligation to provide a boat with warriors annex oarsmen in case of seaborn threats (Van der Tuuk 2007, 2012). For more facts worth knowing concerning heercogge, consult the intermezzo ‘Conscription in the Early Middle Ages’ in our post A Frontier known as Watery Mess: the Coast of Flanders.

In the southern coastal zone of Norway, district assemblies also dealing with the coastal defence, were called skipreiða or skiplagh in eastern Sweden. More inland in Sweden and Norway the centena thing was called herað. Besides a military organization it also dealt with other matters relevant for the community (Ødegaard 2013). In modern Sweden it is called härad and in modern Norway herred. In the region of Svealand in Sweden it was called hundari. Its origin therefore to deliver a band of hundred warriors (Sanmark 2017).

From research into centena thing sites in the region of Skåne in Sweden we know these were generally located near old roads in sight of execution places, i.e. the gallows, close to but never within the premises of villages, and often on the boundaries of church parishes (Svensson 2015). At the same time, the location of the thing sites of the hundred were not cast in concrete and could be moved from time to time, albeit on average within a radius of no more than 10 kilometers. Communication routes, road and water, and the (changing) geography of power seem to have been decisive for determining the location, like fords through waterways. Rivers and streams, especially, could be holy and symbolize the boundary between the world of the living and the dead. Furthermore, in the case of south-eastern Sweden, the assemblies of the hundred continued to be held in the open air throughout the Middle Ages (Sanmark 2009).

The centena thing had mandate to decide on capital crimes, explaining the visual proximity of the gallows. Hence, cash on the barrel. Because of, among other, presence of gallows on top of Donderberg Hill, next to Grebbeberg Hill near the town of Rhenen in the Central Netherlands, we do not rule out that Grebbeberg Hill might have been an old thing site too. Possibly even under jurisdiction of Frisian rulers for a while. Read our post Don’t believe everything they say about sweet Cunera for more on the history of Grebbeberg Hill.

A question concerning the execution of the judgement in capital crimes is whether these were done on a fixed time. In the city of Amsterdam of the early modern period, executions always did take place at noon on Saturdays (Thuijs 2020).

pagus thing

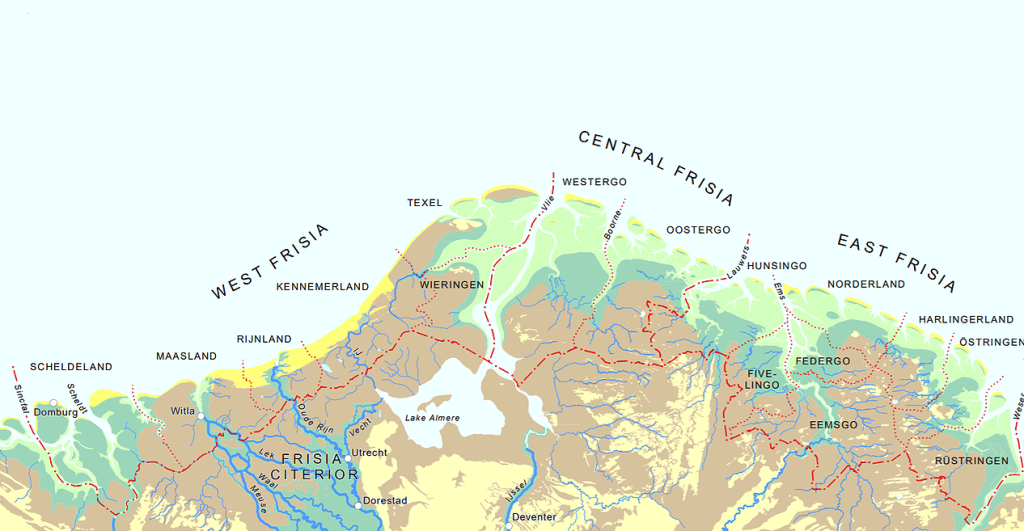

The pagus is considered the oldest building block in the ‘administrative organisation’ of Frisia. The pagi of early-medieval Frisia have been firmly established through historic research, and it shows that its boundaries were often defined by rivers (Nijdam 2021). In total sixteen pagi have been identified (De Langen & Mol 2021). These are from south to north along the North Sea coast the pagi: Scheldeland (i.e. mouth River Scheldt), Maasland (i.e. mouth River Meuse), Rijnland (i.e. mouth River Rhine), Kennemerland, Wieringen, Texel, Westergo, Oostergo, Hunsingo, Fivelingo, Norderland, Federgo, Eemsgo, Harlingerland, Östringen, and Rustringen.

Beside these sixteen pagi, also the four pagi Niftarlake, Flandrenis, Rodanensis and, perhaps, Wasia (Land van Waas) should be included as being part of early-medieval Frisia. In the latter, at least the area of Vier Ambachten in the current region of Zeelandic Flanders, also early-medieval Frisian law was being practiced. Read our post A Frontier known as Watery Mess: the Coast of Flanders for more information about the southern sway of the Frisians. For more information about pagus Nifterlake, i.e. the area of the River Stichtse Vecht in the province of Utrecht, check our post Attingahem Bridge. Therefore, twenty pagi in total and a same number of thing sites existed in Frisia in the Early Middle Ages.

The thing of the pagus level gathered three times a year. In Scandinavian countries the regional thing is commonly called althing or alþingi ‘everyone’s gathering’. Of course, always on a Tuesday too. Evidence of thing sites in Frisia is basically circumstantial but the following six sites or places are quite probable (Dijkstra 2011, Nijdam 2021). From south to north these are: Naaldwijk for pagus Maasland, Luttige Geest at Katwijk for pagus Rijnland, Schepelenberg at Heemskerk for pagus Kennemerland, Sommeltjesberg at De Waal for pagus Texel, Franeker for pagus Westergo, and Dokkum for pagus Oostergo. So, six down and fourteen sites to go.

Another thing site might have been at Bruges, of the pagus Flandrensis. From the late tenth century, it is known a placitum generale ‘everyone’s gathering’ or gouwding took place here (Henderikx 2021). Another thing site, that of the pagus Scheldeland, must have been at the island of Walcheren in the province of Zeeland. From the Vita sancti Willibrordi ‘life of Saint Willibrord’ written by Abbot Thiofrid of the Abbey of Echternach in 1103, we know that at least early in the twelfth century gouwding meetings were held on the island. Where exactly, we do not know. Maybe near the modern town of Domburg or near portus ‘port town’ Middelburg. Lastly, local folklore has it that at Mertsel in the city of Antwerp a thing was located too, but we haven’t found any scholarly support for it. The location could be fitting, though, next to the River Scheldt and near the border of two parishes as well.

We have put the plausible thing sites (of the pagus level; the althing) of Frisia in a map:

civitas thing

The thing of the civitas level, the high level or top-level thing, is quite obscure as well. These meetings probably took place once a year, and probably at Midsummer (Sanmark 2017). Concerning Frisia, based on the late eighth-century administrative distinction of the Lex Frisionum of three regions, it is assumed there was a civitas thing for:

- the part of Frisia inter Flehi et Sincfalam, i.e. West Frisia between the River Vlie and Sincfala, which is the coastal plain of West Flanders;

- the part of Frisia inter Laubachi et Flehum, i.e. Mid Frisia (also Central Frisia) between the River Lauwers and the River Vlie, and;

- the part of Frisia inter Laubachi et Wisaram, i.e. East Frisia between the River Lauwers and the River Weser.

Most laws of these three civitas jurisdictions were similar but with some differences, especially on the height of tariffs for compensation. Check our post You killed a man? That’ll be 1 weregeld, please to understand how compensation for committed crimes was organized in the feud-society of high and late-medieval Frisia.

Not of the Frisians but of their ‘cousins’ the Saxons, a relevant account concerning the thing assembly organization has been preserved in the anonymous Vita Lebuini Antiqua ‘the old Life of Saint Lebuinus’ (Sanmark 2017). Saint Albuinus, Apostle of the Frisians, was active in Frisia and Saxony and died around the year 775 at the town of Deventer in the Netherlands. The relevant passage of the account of the Vita is the following:

In olden times the Saxons had no king but appointed rulers over each pagus; and their custom was to hold a general meeting once a year in the centre of Saxony near the river Weser at a place Marclo. There all the leaders used to gather together and they were joined by twelve noblemen from each pagus with as many freemen and serfs. There they confirmed the laws, gave judgement on outstanding cases and by common consent drew up plans for the coming year on which they could act either in peace or war.

Vita Lebuini Antiqua

The site Marclo, supposedly near the River Weser, is more than interesting. The etymology of Marclo is mark meaning ‘(border) land, demarcated area’, and lo meaning ‘light, open forest’ (Van Berkel & Samplonius 2018). Furthermore, there is a place name Markelo, called Marclo in old documents, in the Netherlands today. Located in Saxon cultural area, not far from Deventer where Saint Lebuinus died; 25 kilometers as the crow flies. Also, at Markelo you can find the Friezenberg ‘Frisians hill’, a 40 meters-high hill, and the Dingspelersberg. The latter is composed of dincspel ‘thing-jurisdiction’ and berg ‘mound/hill’. An etymology comparable to Dinxperlo, a town a bit more to the south from Markelo. The finish it off, close to the Dingespelersberg lies the Markelerberg or Markelose Berg. In the Late Middle Ages, sovereign rulers of the region, i.e. the bishop of Utrecht, were still being honoured on this hill called the Marckeberghe then. Markelo, and the Marckeberghe, was a sacral place and part of the cult of the Holy Blood that existed here until the seventeenth century. A sacred stone that received Christ’s blood was part of the cult (Frijhoff website).

The Friezenberg near Markelo is not the only Friezenberg in the world. In Germany exists also a Friesenberg, in Danish language Friserbjerg. It is a town district of Flensburg where a burial mound existed, including a Grenzstein, a stone marking the border between two districts. All elements taken into account, it might have been a thing site as well.

pan-Frisia thing

The question whether there was even an overarching thing for the whole of Frisia in the Early Middle Ages, thus covering the three civitates West Frisia, Mid Frisia and East Frisia, remains unanswered.

A strong candidate for the pan-Frisia thing might be Fositesland. Earlier, we already mentioned the god Foseti, meaning ‘the god that presides’. Fositesland ‘president’s land’ is mentioned in the Vita sancti Willibrordi Traiectensis episcopi ‘life of Saint Willibrord bishop of Utrecht’ written by the clergyman from Northumberland, Alcuin of York (circa 735-804). Alcuin described an encounter on Fositesland between Saint Willibrord, Apostle to the Frisians, and the heathen King Radbod of Frisia. An encounter that took place around the year 692. Fositesland was an island located in confinio Fresonum et Danorum ‘between Frisia and Denmark’, according to Alcuin. A bit later, in the year 718, Saint Wulfram visited Heligoland too. Through a miracle, Saint Wulfram prevented two boys from being sacrificed to pagan gods. Both the account of Willibrord and of Wulfram speak of a holy well located on the island. And, according to the early-eleventh-century chronicler Adam of Bremen, Heligoland was a popular place for hermits. In other words, the island was probably of great religious importance to the Frisians throughout the Early Middle Ages. Indeed, a holy land.

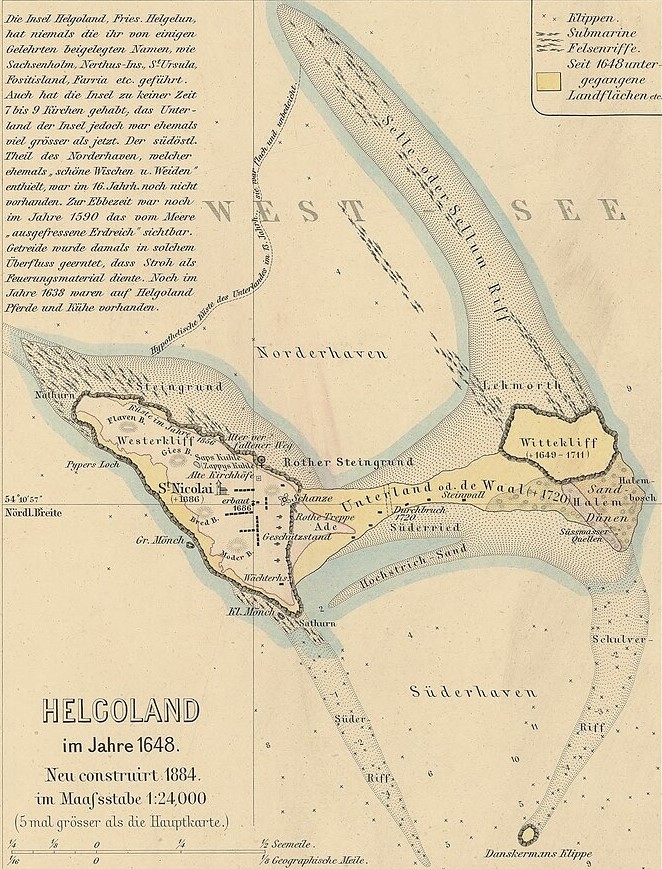

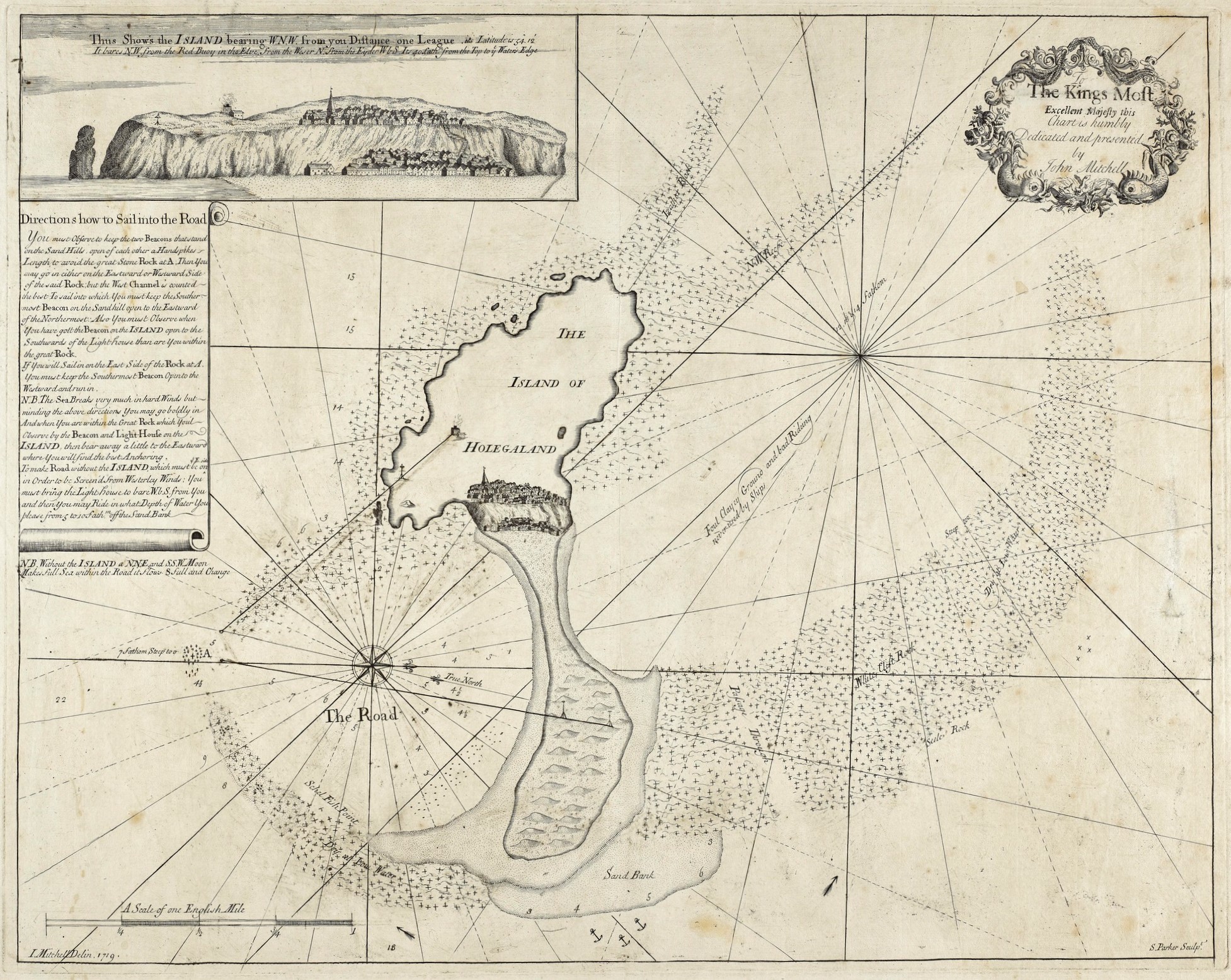

Commonly, Fositesland is identified with the North-Frisian red-rock island Heligoland in the German Bight at the North Sea (Halbertsma 2000), but this is not fully certain. An island possibly known by the Romans under the name Basileia and known for its amber (Looijenga, Popkema & Slofstra 2017). In fact, today it is two islands that used to be connected well into the eighteenth century.

Sometimes, the Wadden Sea island Ameland, or island Texel, is considered to be Fositesland (Dykstra 1966, Halbertsma 2000, Brouwers 2013). Frisian folktales tell that island Ameland was known as Fostaland or Fosland, after the goddess Fosta, in ancient pagan times. After Christianization, a monastery was founded on Ameland with the name Foswerd. Later, the monastery was relocated to the village of Ferwerd on the mainland (Dykstra 1966). Also, the Oera Linda book, a late nineteenth-century document with a fictional history of Friesland, speaks of the burgh Fåstaburgt and the templum Foste on the island Ameland. Lastly, on Ameland, near the village of Nes in the center of the island, a little pond carries the names Willibrord dobbe or Fosite bron.

Anyway, geographically speaking, Heligoland’s location is quite central within the Frisian cultural area in the Early Middle Ages. Other names for the island are Helgoland, Hellgeland, and, of course, deät Lun or deat Lünn ‘the land’ in Halunder language, i.e., the native Frisian speech.

That a pan-Frisia thing would take place there, is speculation since no reference to assemblies is made in historic texts. With the high, red cliffs and free-standing stack called Lange Anna ‘tall Anna’, and being an mound surrounded by water, it does meet the requirements of being an imaginative and sacred site, for sure. The name Heligoland meaning ‘hillige lân‘ or ‘heiligen Land‘ or ‘holy land’ has parallels with thing assembly sites in Scandinavia. Helgøya ‘holy island’ in Lake Mjøsa in Norway is a former thing site, and there are a number of other thing sites named holy island as well (Sanmark 2017). Note that in the Early Middle Ages Heligoland was a much bigger island and that much of the island has been washed away by the sea in the meantime.

Gatherings of modest numbers of Frisians from the various Frisian lands, including those from the regions Land Wursten and Land Wurden in Germany, take place on island Heligoland every three year, nowadays. At first, these folkloric gatherings were named Sternfahrt der Friesen ‘rally of Frisians’ but since 1998 the event is known as Friesendroapen ‘Frisians-moot’.

island Heligoland in 1648, 1719 and today

It is only in the High Middle Ages we are certain that a thing for pan-Frisia exists. Established somewhere around the year 1200. This imaginative thing site was near the modern town of Aurich in region Ostfriesland and called Upstalsboom. Not too far from island Heligoland in a way. The Upstalsboom thing cannot be much older than 1200 because it is located in a peat land area which were only commercially exploited during the High Middle Ages. Too young therefore (Nijdam 2021).

The Upstalsboom thing gathered once a year on the Tuesday after Pentecost, with delegates from all the so-called Seven Sealands. The Seven Sealands were divided into four fardingdela. The thing of the fardingdela was called the liodthing and extraordinary things were called the bothing, as we have mentioned earlier. Bothing derives from ‘(ge)boden ding’ meaning the commanded thing. This is, by the way, a different explanation of the name bodthing from the one offered earlier this post (Iversen 2013), where it is connected with the idol Bede or Beda found on the stone pillar of Frisian mercenaries at Hadrian’s Wall, Late Antiquity. The four fardingdela ‘quarters’ had twice a year a thing called the lantding. The Old Frisian term fardingdela resembles the Old Icelandic term fjórðungar for regional districts.

The Upstalsboom assembly was primarily an effort to combine forces against the surrounding feudal powers that posed a growing threat. Frisia was in essence just a loose collection of small, lord-free, farmer republics and therefore had a hard time organizing their guerrilla, militia defence. Whilst their surroundings possessed a knighthood and professional mercenary armies. Read more about this history in our post Upstalsboom: why solidarity is not the core of a collective and why the whole Upstalsboom treaty failed. To get an idea of the medieval Frisian guerrilla warfare, check our blog post Guerrilla in the Polder. The Battle of Vroonen in 1297.

2. Other Thingies

There are indications thing gatherings were also moments for religious festivals, regional market and circuses or games, although some scholars doubt whether markets were that prominent (Mehler 2015). On the other hand, close links can be observed between thing sites, pre-Christian cult sites, medieval churches, games and markets. The Þingvellir on Iceland is the biggest market of the year. Furthermore, horse races and horse fights were popular everywhere during the thing in the Viking Age (Ødegaard 2018). In Norway a seasonal meeting called skeið survived well into the seventeenth century, and horse racing and fighting without saddles was still popular (Loftsgarden, et al 2019). But also think of wrestling and ritually slaughtering of wild boar (Sanmark 2017).

In other words, thing gatherings were also important events for creating collective memories and for social cohesion. Therefore, be suspicious when it comes to so-called medieval seend or see churches ‘ecclesiastical courts’ within a parish because they are strong candidates for being a former thing site. Within Frisia, the boundaries of parishes show likeness with those of the pagi. Like the pagi, parishes are often situated in river basins as well (De Langen & Mol 2021). An old and important settlement of former West Frisia is Medemblik where also a seend church was located. One of the oldest settlements in the area, proven from the second half of the seventh century. Might there have been a former thing site?

The fact that thing sites, churches, religious activities, trade and games happened together, might also offer a different perspective for the high-medieval church murals of fighters in the churches of the villages of Stedum, Westerwijtwerd and Woldendorp, and the horse-fighters in the church of the village of Den Andel, all located in the province of Groningen, former Frisia. Traditionally, these fighters are associated with dual fighters. Fighters, known as kempa in the Old Frisian language, were ‘hired’ by parties who were having a legal dispute to perform an ordeal. But are these murals really depicting kempa, or are they perhaps impressions of games and circuses during the thing event near the church?

3. Things That Matter

Most of the Middle Ages, Frisia did not have any lord or central ruler. Nevertheless, the pagi and its thing were stable and kept functioning all the way through from the early to the late medieval periods. Even during times when Danish and Frankish rulers stirred things up temporarily, the thing kept doing its thing. These assemblies, to put it differently, proved to be the core of the community (Nijdam 2021).

In West Frisia, the coastal area from the region of West Flanders to the province of Noord Holland, where counts and feudalism did gain control over the area in the course of the Middle Ages, it was for long practice that a new count would be present at the thing to receive the trust of the people, often after negotiations between the people and the new count about the mutual rights and duties. During the gathering at the thing, the new count swore to uphold and defend the rights and obligations of all his subjects. In return the subjects swore loyalty and pay taxes (Dijkstra 2011). A similar practice, by the way, existed in Sweden; a ritual called eriksgata. The word Eriksgata derives from einriker ‘absolute king’ and gata ‘journey, road’. The new king would travel through the country along important thing sites (Sanmark 2017).

However, today parliaments broadly are being portrayed as stamping machines of the ruling parties, and its members as yes-men of the ones who hold power. Therefore, as promised at the start of this blog post, we would not only observe the past but also make some recommendations for the future. For this, it is time to briefly step into the political arena of the thing, if all the gods and our ancestors allow us.

Learning from an at least 2,000-years-old tradition of the thing, after those Frisian mercenaries in the Roman Army wrote about it, the following five advices are given to the Members of the present thing, and who are: Members of Parliament, Speakers of the House of Representatives, Presidents, (Prime) Ministers, (Under) Secretaries and (High) Councils of State.

- Frequency – Concerning the national thing, the civitas level, limit the number of meetings per year and, of course, only on Tuesdays. Less assembling helps the thing to focus on broad outlines and less on what is on the news the evening before. It also helps to limit unnecessary legislation which partially is born out of political profile desire. Appreciate the little things too. Realize there are namely things at the regional and local level too, capable of taking care of issues. That is, if you let them have the powers to do so (Knoop 2022). If the traditional three times per year for the national thing feels as if the stretch is too large, reduce the number of meetings drastically anyway.

- Oath – Remind the members of the thing of the fact that they work and speak under oath and have, or at least ought to have, some personal honour. Be aware of the thriteen-centuries-old Frisian runic inscription ᛗᛞᚫ ᛒᚩᛞᚪ(edæ boda) carved in the wooden sword of Arum meaning ‘de geboden eed / the oath commanded’. In addition, reconsider whether violating oaths and perjury shouldn’t have more attention and greater consequences as well. We understand, many Members of the modern thing often cannot recall events in their memory due to their busy agendas, and because of for being in office so long. But it is still worth a try, we think.

- Transparency – Essential for the medieval thing was that the meeting and debates occurred in open-air. Of course, this is still practice because people can watch the meetings on the web or on the public tribunes. However, much debate that should take place during the thing, takes places in back rooms instead, combined with a dominant party discipline. Current initiatives for a more open and transparent government are praiseworthy, but they should also be developed by the thing for the thing. Limit yourself!

- Shelf life –The thing was an important institute to prevent that too much power would accumulate with few. This has derailed completely, even within democracies, as everyone knows today. Consider therefore to formulate rules concerning the maximum number of terms for the Members to participate in the thing (Elzinga 2021). Every product has a maximum shelf life, whether this is canned tuna, tomatoes, packaged chicken, or politicians, officials and administrators. Make sure it is a serious reduction concerning the standing practice. A positive side effect is that Members do not have to dig too deep into their memory anymore, which helps to strengthen the effectiveness of the oath (see advice 2).

- Internet participation – Study on a different interpretation of the concept ‘The Internet of Things’. It might open new ways in consensus building through gathering. It might help the thing! Think of initiatives like Citizen’s Assemblies, the Sortition Foundation and the guidebook of the UN Democracy Fund (Talmadge 2023). And, instead, Members of the thing should refrain from producing fact-free opinions on the social media, and solely utter them at the thing (see also under 3). In province Friesland they came up with the internet consultation Stim fan Fryslân ‘voice of Friesland’ and in the Netherlands, focussing on climate and environment, with Bureau Burgerberaad ‘bureau citizen deliberations’.

Note 1 – We suggest that the original pillar (or at the very least a replica thereof) dedicated to the thing erected by the band of Frisian mercenaries at Fort Housesteads at Hadrian’s Wall in the third century, will be relocated to Het Binnenhof in The Hague in the Netherlands. Het Binnenhof is the ground where parliaments and governments of the Netherlands have gathered for the last four to five centuries. And, in accordance with ancient traditions, the former gallows named ‘t Groene Zoodje ‘the green turf’ is located near the thing site Het Binnenhof at Plaats Square in The Hague. Imagine, the almost 2,000-year-old stone Frisian pillar of fort Housesteads standing at this spot. How much greater and more symbolic do you want it to be? And Het Binnenhof also happens to be the oldest house of parliament in the world still in use.

Why did we have to come up with this idea anyway? The Netherlands as birthplace of the thing. A tradition of public consensus building through gathering, historical and archaeological traceable in the central river area from the Late Antiquity, and -uniquely- continuing to function throughout the whole Middle Ages in the former small republics of Frisia. How much better than all the statues of former grey statesmen placed on socles, too.

If the national parliament in The Hague for some reason doesn’t feel like adopting this pillar and realising this initiative, at least the regional parliament of province Friesland, the Provinsjale Steaten, should.

Note 2 – The featured image of this post is from the movie The Fantastic Four (2005), with The Thing being the ‘rocky type’ superhero. In 1982 and 2011 movies were released called The Thing. In both movies horrible creatures that must be killed. Of course, this is exactly not what we propose to do. Therefore, out of the three we chose the superhero.

Note 3 – According to tradition, the former, early-medieval circular fortress near Tinnum on the island Sylt in Nordfriesland, is also a thing site or Dinghügel as locally referred to.

Suggested music

- Teach-In, Ding-a-dong (1975)

- Survivor, Eye of the Tiger (1982)

- Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Two Tribes (1984)

Further reading

- Ahlness, E.A., The legacy of the Ting: Viking Justice, Egalitarianism, and Modern Scandinavian Regional Governance (2020)

- Berkel, van G. & Samplonius, K., Nederlandse plaatsnamen verklaard. Reeks Nederlandse plaatsnamen deel 12 (2018)

- Brouwers, L.L., De vrije heerlijkheid. Amelandgedichten (2013)

- Buma, W. J., In runefynst út Rasquert (1966)

- Clerinx, H., De god met de maretak. Kelten en de Lage Landen (2023)

- Corthals, J., De ‘Hoge Raad’ en de ‘Nederlanden’. Over straf, rechterschap en maatschappij (2014)

- Couperus, L., Van oude menschen, de dingen, die voorbij gaan… (1904)

- Cowie, A., Things: Old Viking Parliaments, Courts And Community Assemblies (2020)

- Dijkstra, M.F.P., Rondom de mondingen van de Rijn en Maas. Landschap en bewoning tussen de 3de en de 9de eeuw in Zuid-Holland, in het bijzonder de Oude Rijnstreek (2011)

- Dykstra, W., Uit Frieslands volksleven. Van vroeger en later (1966)

- Ehlers, C., Between Marklo and Merseburg: Assemblies and their Sites in Saxony from the Beginning of Christianization to the Time of the Ottonian Kings (2016)

- Elzinga, D.J., Alle politieke bestuurders moeten na acht jaar opstappen (2021)

- Fernández-Götz, M. & Roymans, N., The Politics of Identity: Late Iron Age Sanctuaries in the Rhineland (2015)

- Fischer, K., Schmuggler, Spione und Halunder: Was jeder über Helgoland wissen sollte (2023)

- Frijhoff, W., Markelo, Heilig Bloed (website Meertens Instituut)

- Halbertsma, H., Frieslands oudheid. Het rijk van de Friese koningen, opkomst en ondergang (2000)

- Henderikx, P.A., Walcheren en de Vita sancti Willibrordi van Thiofried van Echternach (2021)

- Hunnink, V., Tacitus. In moerassen en donkere wouden. De Romeinen in Germanië (2015)

- IJssennagger, N.L., Runenstaf van Bernsterburen (2012)

- Iversen, F., Concilium and Pagus – Revisiting the Early Germanic Thing System of Northern Europe (2013)

- Kingma, S., Asega, is it Dingtiid? (2022)

- Knol, E. & Looijenga, J.H., A Tau staff with runic inscriptions from Bernsterburen (Friesland) (1990)

- Knoop, B., Steeds meer taken, steeds minder zeggenschap: de lokale democratie staat onder druk (2022)

- Kort, de J.W., Groenewoudt, B. & Heeren, S. (eds.), Goud voor de goden. Onderzoek naar een cultusplaats uit de vroege middeleeuwen in het natuurgebied Springendal bij Hezingen (gemeente Tubbergen) (2023)

- Lendering, J., Het Oera Linde-Boek – Aanklacht tegen christelijk fundamentalisme (2019)

- Lendering, J., The Batavian Revolt (2011)

- Loftsgarden, K., Ramstad, M. & Stylegar, F.A., The skeid and other assemblies in the Norwegian ‘Mountain Land’ (2017)

- Looijenga, T., De volstrekte behoefte tot echte kennis van het waar gebeurde (2023)

- Looijenga, T., Runes around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150-700: texts & contexts (1997)

- Looijenga, T., Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions (2003)

- Looijenga, A., Popkema, A. & Slofstra, B., Een meelijwekkend volk. Vreemden over Friezen van de oudheid tot de kerstening (2017)

- Mehler, N., Þingvellir: A Place of Assembly and a Market? (2015)

- Mol, J.A., Galgen in laatmiddeleeuws Friesland (2006)

- Nijdam, H., Law and Political Organization of the Early Medieval Frisians (c. AD 600-800) (2021)

- Nijdam, H., Spiekhout, D. & Dijk, van C., De culturele betekenis van het tweesnijdend zwaard in middeleeuws Frisia (2023)

- Neijens, S., Oudste zonnekalender van Nederland ontdekt in Tiel (2023)

- O’Grady, O.J.T., MacDonald, D. & MacDonald, S., Re-evaluating the Scottish Thing: Exploring A Late Norse Period and Medieval Assembly Mound at Dingwall (2016)

- Ødegaard, M., State Formation, Administrative Areas, and Thing Sites in the Borgarthing Law Province, Southeast Norway (2013)

- Ødegaard, M., Thing sites, cult, churches, games and markets in Viking and medieval southeast Norway, AD c.800–1600 (2018)

- Panhuysen, L., De Ware Vrijheid. De levens van Johan en Cornelis de Witt (2005)

- Renswoude, van O., Het heilige land (2019)

- Ritsema, A., Heligoland, Past and Present (2007)

- Rüger, J., Heligoland. Britain, Germany, and the struggle for the North Sea (2017)

- Sanmark, A., Administrative Organisation and State Formation: A Case Study of Assembly Sites in Södermanland, Sweden (2009)

- Sanmark, A., The case of the Greenlandic assembly sites (2009)

- Sanmark, A., Viking Law and Order. Places and Rituals of Assembly in the Medieval North (2017)

- Savelkouls, J., Het Friese Paard (2016)

- Schuyf, J., Heidense heiligdommen. Zichtbare sporen van een verloren verleden (2019)

- Semple, S., Sanmark, A., Iversen, F. & Mehler, N., Negotiating the North. Meeting-Places in the Middle Ages in the North Sea Zone (2021)

- Siefkes, W., Ostfriesische Sagen und sagenhafte Geschichten (1963)

- Spiekhout, D., Brugge, ter A. & Stoter, M. (eds.), Vrijheid, Vetes, Vagevuur. De middeleeuwen in het noorden; Nijdam, H., De middeleeuwse Friese samenleving. Vrijheid en recht (2022)

- Svensson, O., Place Names, Landscape, and Assembly Sites in Skåne, Sweden (2015)

- Talmadge, E., Citizens’ assemblies: are they the future of democracy? (2023)

- Things sites.com (website)

- Teutem, van S., Waarom de Tweede Kamer niet werkt (2022)

- Thuijs, F., Moord & doodslag. In drie eeuwen rechtsgeschiedenis (2020)

- Tjeenk Willink, H., Kan de overheid crises aan? Waarom het belangrijk is om groter te denken en kleiner te doen (2021)

- Tudor Skinner, A. & Semple, S., Assembly Mounds in the Danelaw: Place-name and Archaeological Evidence in the Historic Landscape (2016)

- Tuuk, van der L., Deense heersers en de Friese kogge in de vroege Middeleeuwen. 2. De koggenorganisatie en de rol van de Deense heersers (2007)

- Tuuk, van der L., Herekoge in Vredelant (2012)

- Tys, D., Cult, assembly and trade: the dynamics of a ‘central place,’ in Ghent, in the County of Flanders, including its social reproduction and the re-organization of trade, between the 7th and 11th centuries (2018)

- UN Democracy Fund & NewDemocracy Foundation, Enabling National Initiatives to Take Democracy Beyond Elections (2019)

- Visser, A., Wat heeft hij in zijn Mars en wat voerde hij in zijn schild? (2023)

- Vries, O., Asega, is het dingtijd? De hoogtepunten van de Oudfriese tekstoverlevering (2007)

- Vries, O., Ferdban. Oudfriese oorkonden en hun verhaal (2021)

- Vries, O., Instances of direct speech, authentic and imaginary, in Old Frisian (2022)