Beauty is the best guarantee for quality and success. At least, this is how farmers in the province of Friesland thought of dairy cattle for (too) long. The better the exterieur ‘exterior’ of a cow, the better its milk yield. Velvety hide, size, expressive head, straight back, strong legs, sharply defined black and white spotted markings, fine horns, clear teats, etc. All features considered signs of good productive cattle. Even when evidence was piling up that the black-pied dairy cows of America had become far superior to the up till then untouchable Friesian breed, farmers and cattle breeders in the province of Friesland simply put their heads in the sand. An illustration of what happens often in human history. The moment you think you have achieved the highest, you are actually in free fall already. The moment your Prime Minister cheerfully and carefree says: “What a cool little country we live in!”, better buckle up for a rough ride ahead. Below, we will tell the story of the Friesian cow. Its rise, its fall, and its resurrection.

This blogpost is about the Friesians, not the Frisians. Friesians are cows (and horses) originating from province Friesland, and the Frisians are famous for it. Besides the name Friesian, it is also known by names as Holstein, Black and White, and Bontekoe meaning ‘pied cow’. Classic cheesy German jokes about Frisians rest on this cattle trademark, like: Wie viele Ostfriesen braucht man um eine Kuh zu melken? Acht. Vier halten das Euter fest, die anderen heben die Kuh hoch und runter ‘How many East-Frisians do you need to milk a cow? Eight. Four hold the udder, the others lift the cow up and down’, or: Warum tragen Ostfriesinnen beim Melken Kopftücher? Irgendwie muss man sie ja von den Kühen unterscheiden können ‘Why do East-Frisian women wear headscarves when milking? You have to be able to distinguish them from cows somehow’, or; Woran merkt man, dass man in Ostfriesland ist? Die Kühe werden schöner als die Mädchen ‘How do you know that you are in Ostfriesland? The cows become more beautiful than the girls’. Etcetera etcetera.

Despite, as we will see in this post, perceived beauty and appearance do play an important role in the history of the dairy cow, these jokes do not do justice to the impressive world history of the Frisian dairy industry and the Friesian cow. In recent history, cattle from Friesland have largely defined the dairy food supply of the modern world. After reading this post, going to the supermarket to buy some milk, butter, butter milk, whipped cream, custard, yoghurt, ice cream, infant formula, quark, cheese etc., will never be the same again.

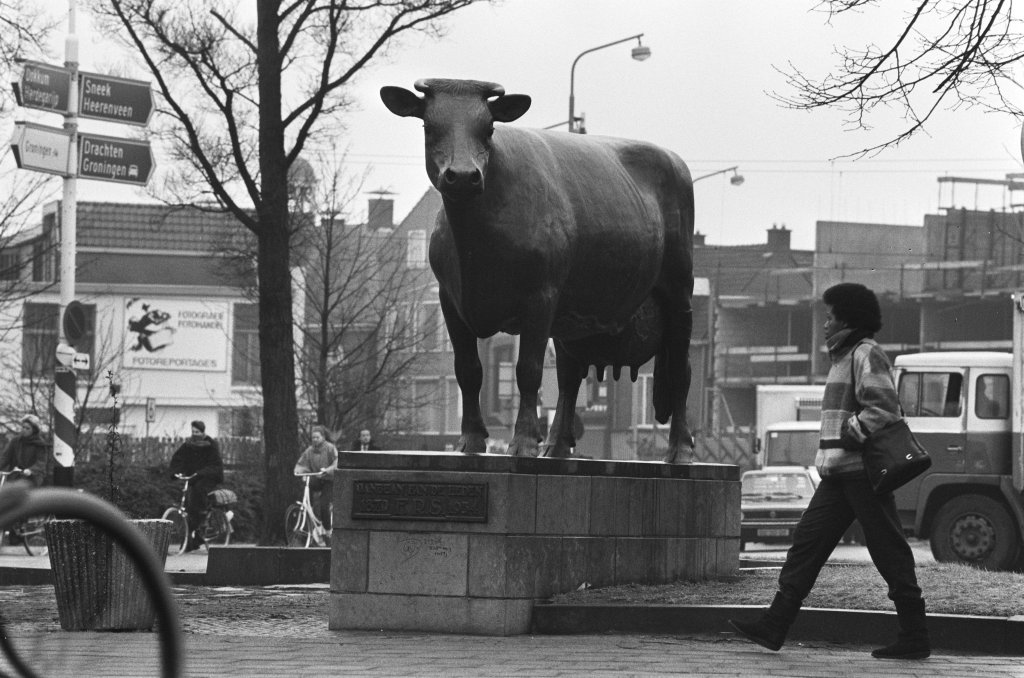

Albeit being Christianized for a thousand years already, the smugness and adoration of the dairy cow was that great in the decennia after the Second World War, that people forgot the teachings of the Book of Exodus. When the people of Israel lost their faith in God while wandering through the Sinai desert and created an idol, namely a statue of a calf made of gold. The same idleness namely happened in the Netherlands, where you can find more than one statue of dairy cows and bulls. To list just a few prestigious examples: statue of bull Skalsumer Sunny Boy in Wirdum (1998), statue of bull Dirk 4 in Hoornaar (1981), statue of bull Adema 21 at the Westfries Museum in Hoorn (1960), statue of the Exporum Bull, also known as Sjoerd 1, in Cuijk and originally at the World Expo in Brussels (1958), and, of course, the holy statue of cow ús mem, meaning ‘our mother’ in Mid-Frisian language, in Leeuwarden (1954). Incidentally, all cows mentioned received Frisian personal names.

Amazingly too, each year best Dutch film actors, film makers etc. are awarded with a Gouden Kalf ‘golden calf’ statue and are thrilled when it is handed to them. And, as far as we are aware of, non of them were followers of Hinduism. So, when and where did all this idolatry of cattle start?

1. Early Beginnings

The pair ‘Frisians and cattle’ go back a long, long way. The first account in which we learn Frisians kept cattle, dates from the first century AD. It is the report of the Roman politician and historian Tacitus (ca. AD 56-120) about when the tribe of the Frisii ‘Frisians’ revolted against the Romans. It was a tax revolt and happened after centurion ‘commander’ Olennius demanded that the Frisians would supply the Roman army with bigger cowhides than hitherto. Cowhides had to have the measurements of a wild auroch, henceforth. Their cattle, however, were much smaller than aurochs (Auerochse or oerossen in German and Dutch languages), and consequently the Frisians could not comply with these new tax requirements. From archaeological research we know the cow’s height at withers was just over a meter back then (Hullegie & Prummel 2015, Nieuwhof 2018). Size of an auroch at withers was about 1.5 metres.

As a side note, the rune ᚢ of the early-medieval Anglo-Frisian futhorc alphabet is named ur meaning auroch. Dutch pronunciation of oer(os) is the same as ur (ox). Read for more about runes our blog post Scratching runes is no different from spraying tags.

You would think the smart Romans must have known they were asking the impossible. So, what was it they were after? Provoking the Frisians? Or were the Romans concerned about the quality of such small cattle and wanted to stimulate cattle breeding among the Frisians? A herd book avant la lettre. Anyway, for being in default, Olennius demanded from the Frisians their cows, their acres, and even their wives and children. Governments tend to be very rigid when it comes to not paying your taxes properly, whatever your ‘excuse’ might be. Eventually, the Frisians revolted in the year AD 28. An uprise that became known as the Battle of Baduhenna, which was won gloriously by the Frisians. About 1,300 Roman soldiers died during the confrontation. Somewhat assisted by the chaotic organization on Roman side.

For more about the Battle of Baduhenna, check our post Pagare il fio. This Italian phrase, by the way, literally means ‘pay the cattle’ (compare fio also the English word fee or Dutch word fooi for price, meaning compensation and tip), and it has its origins in Germanic culture. The Mid-Frisian and German words for cattle are still fee and Feh. Moreover, one of the letters of the early-medieval Anglo-Frisian runes, also called futhorc, is feh or feoh and written as ᚠ meaning wealth. Baduhenna, by the way, was a forested area in modern province Noord Holland in the surroundings of the city of Amsterdam.

The Battle of Baduhenna is not the beginning of Frisians breeding cattle. Habitation of the tidal marshlands of the northern Netherlands started in the late seventh century BC, what is called the pre-Roman Iron Age. The same time when Romulus and Remus founded Rome. Settlers arrived in this area from the northern parts of province Noord Holland, the Drents Plateau and the German Bight (Nieuwhof 2018). Recurring texts on the internet that the origin of Holstein Friesian cattle are a crossbred of black and white cows of the Frisian and Batavian tribes are unfounded and no more than the usual web parrot-talk. Together with sheep, cattle were the main resources of the salt-marsh settlers. Height of these cows was between 105 and 110 centimetres at withers. The beasts provided milk, leather, meat and wool. And dung, which was dried to be used as fuel since wood was very scarce on the salt marshes.

Furthermore, wealth was expressed in cattle and were used as a payment. Even the dowry consisted of cattle, according to Tacitus. A weregeld ‘blood money’ originally was expressed in heads of cattle too. The Old-Frisian, early-medieval word scet meant animal/cattle, and the Old-English word for money is sceatta. In other words, cattle literally represented treasure or skat in modern Frisian language. For more about the institute weregeld and the importance of cattle in that context, check out our post You killed a man? That’ll be 1 weregeld, please. The Continent was not unique in this. In early-medieval Ireland an enslaved woman was a unit of value, the so-called cumal, which equalled eighth to ten cows (Raffield 2019).

Archaeological research (Lauwerier et al 2012, Hullegie & Prummel 2015, Prummel & Küchelmann 2022) at the former tidal marshland of the northern Netherlands, showed also that about three-quarter of the livestock during the pre-Roman Iron Age consisted of cattle. Main purposes were beef and beast of burden, like ploughing fields and pulling wagons. When the Romans arrived in the region in the first century AD, the proportion of cattle shrank whilst that of sheep grew. Probably due to a greater demand for wool and cloth by the Roman army. About 55 percent of the livestock consisted of cattle in the period AD 50-300, i.e. the Roman Iron Age. Milk, and hence dairy production, became a more important product of cattle as well during this period. So, you could argue, the economy of the Wadden Sea coast of the Netherlands can boast of a two-millennia-old dairy husbandry.

An interesting and quite uncommon feature of cattle during the Roman Iron Age is that polledness (i.e. hornlessness) of cattle is common in, especially, the coastal Wadden Sea area of the Netherlands. Circa 20 up to 40 percent of the cattle was polled. Within the Roman territory, thus south of the river Rhine, (nearly) no polled cattle has been traced. After the Roman period, polledness disappeared again. Other than some academic speculations about possibly breeding preferences in appearances (Lauwerier 2012), a real convincing explanation for the emergence and disappearance of polled cattle has not been offered yet to our opinion. Above, we sort of joked about the Romans wanting to stimulate the quality of breeding programs by demanding bigger (hides) of cattle, but when you take this specific polledness phenomenon during the Roman period also into consideration, were they perhaps indeed?

Concerning polled cattle today, since the introduction of cubical or free stables in the ‘70s in the last century, cows can move and interact with each other. Before, for centuries or even millennia, cows were fixed with a rope with their heads towards the wall, in two by two between partitions, when stabled. At least, this was customary along the coastal zone of the Netherlands, i.e. Frisia. See also our post An ode to the Haubarg by the green Eiderstedter Nachtigall to learn more about the Frisian style stables and farm houses. Back to the horns, they cause injures among cows in the modern cubicle stables, generate unrest, and pose a security risk for the farmer. For these reasons cows are being dehorned. Besides costs, it moreover gives concerns to animal welfare because it is a painful procedure. Therefore, breeding a new polled dairy cattle is currently being explored.

The dominant gene for polledness does not affect the performance of a cow. Already existing polled cattle breeds are: the endangered Jochberger Hummeln, the Polled Hereford, the Aberdeen Angus, the Galloway, the Belted Galloway, the German Angus, and the Fjäll (Windig et al 2015, Hullegie & Prummel 2015). Beautiful (beef) animals, although a Texas Longhorn or Ankole-Watusi cow in the fields with their ornamental horns, would be nice for a change.

After the Roman period, between around AD 300 until 1100, the percentage cattle of the total livestock lies between 25 and 45. From around 1100, the proportion of cattle increased again to circa 50 percent. This increase is attributed to a profound change of the medieval landscape. It is from around the year 1000, that bigger dykes are being built along the Wadden Sea coast to block the sea altogether. What used to be a brackish to salty environment, as a consequence turned fresh. An indirect effect of this shift is that sheep became more vulnerable to the fasciolosis, a parasitic worm. Fasciolosis is transmitted to its host via little freshwater snails. These snails could not survive in the previous saline landscape. But with the arrival of the much hailed dykes, they do. Cattle as such are less vulnerable to fasciolosis than sheep.

Besides the transition from a saline to a sweet environment, improved safety against floods thanks to the bigger dykes also allowed people to set up farmsteads everywhere. No longer farming was confined to terps, i.e. artificial settlement mounds, and its proximity. This new special freedom improved the agricultural use of the land. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, in province Friesland alone an estimated 14,000 traditional Frisian longhouses existed, scattered throughout the landscape (Borghaerts 2021).

2. Origins of the Friesian Herd

It is like the saying of Dutch water engineers: “Geef ons heden ons dagelijks brood, en af en toe een watersnood” (‘give us this day our daily bread, and every now and then a great flood’). Expressing the phenomenon of contentment when there is, in fact, no reason for it. To stimulate government officials not to rest on their laurels, and to make available sufficient funds and resources again, a crisis once in while does help. A classic illustration of a hero’s journey of Campbell (1904-1987). Apparently, words and experiences of incidents in the past do not have a lasting effect. Indeed, a theme we touched on at the start of this post. The black and white Friesian cow too, is born out of a catastrophe. One that took place halfway the eighteenth century, as we will see.

In the course of the sixteenth century, hand in hand with the rise of the Dutch Republic and the many technological and scientific innovations that came with it, including the introduction of advanced wind- and watermills (Borghaerts 2021), dairy production became a major commercial economic activity. Especially in provinces Friesland and Noord Holland, including region Westfriesland. Both the areal and, due to more effective management of water levels, the productivity of grasslands was greatly increased. More and better grass and hay formed the basis for a much larger dairy livestock.

Farm operations were modernized as well and made more efficient thus cheaper. In a relatively short period of time, the traditional Frisian longhouses in provinces Noord Holland, Friesland and Groningen were replaced by the high hipped-roof farmsteads we can still see today. Like the stolp, stjelp, kop-hals-romp and oldambtster farmhaus in the three provinces mentioned, but also in region Ostfriesland. All belonging to the family of the so-called Frisian gulf farmhouses, recognizable by the spacious granges to store huge piles of hay under the roof. Until the end of the nineteenth century, dairy processing was organized on the farm itself, especially making cheese and butter. From then on, milk factories took over the dairy processing and farms only produced the white liquid base-ingredient: milk.

The improved dairy-farm concept, essentially small factories, was exported by Dutch businessmen too. With the most impressive farmsteads, the Haubarg, set up on the peninsula of Eiderstedt in region Nordfriesland in Germany, at the beginning of the seventeenth century. These so-called Holländereien ‘Holland spaces/farmsteads’ generated profits for its shareholders and investors. The farmer managing the Holländerei and Haubarg usually was a tenant farmer. Not only the state-of-the-art dairy farm concept was exported, but also many Dutch labourers with skills needed for dairy processing, water irrigation, carpentry etc. followed.

Furthermore, we think, it must be that also dairy cattle from northern Netherlands was exported when these Haubargs were set up in region Nordfriesland. The cow was, after all, the key component of these costly dairy enterprises. All the grass had to go through the four stomachs and the udder of the cow in order to become milk. Climate and habitat, i.e. Wadden Sea marshlands on the peninsula of Eiderstedt, were identical for this cattle to thrive in. For more in-depth information concerning the Haubarg and the Frisian gulf farmhouse in general, read our post An ode to the Haubarg by the green Eiderstedter Nachtigall.

Then fate strikes. Cattle plague, already present in the years 1713 and 1714, hit the dairy husbandry in the years 1744-1746 hard. In particular, the year 1745 was a disastrous one. A catastrophic year in which the cattle population in the northern Netherlands was more than decimated. In province Friesland about 130,000 cows died out of an estimated total population of 160,000. Most farmers in province Groningen even abandoned cattle husbandry and dairy production altogether, and switched to arable farming ever since. Of course, not only the Netherlands was haunted by the plague. Also the wider region.

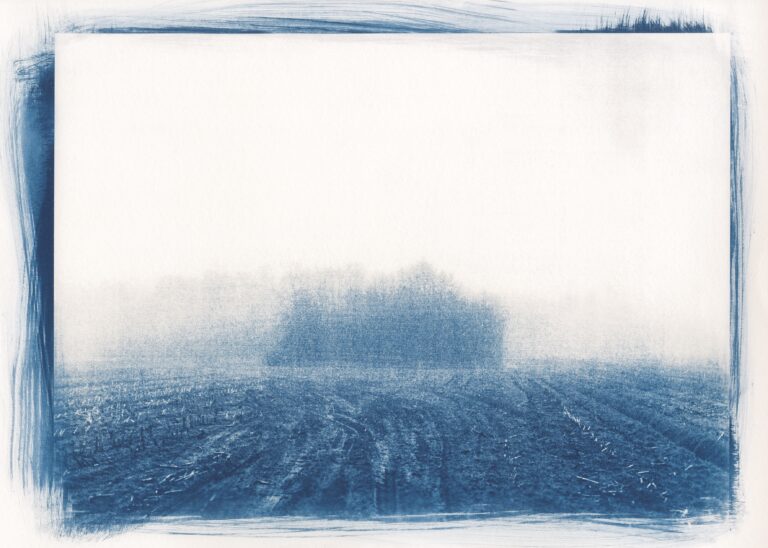

Besides cattle plague, anthrax, mad-cow disease and foot-and-mouth disease affected cattle stocks too. Anthrax appeared regularly until the late ‘50s of the last century. To this day, you can find so-called miltvuurbosjes ‘anthrax bushes’ in the landscape of provinces Friesland and Groningen. Here, on the border of fields and surrounded by a ditch, carcasses of sick cows have been burned and covered with a layer of quicklime and earth to contain the disease. Anthrax bacteria can survive for more than two centuries without a host. So, caution is still needed with the wooded miltvuurbosjes, even after having applied such destructive methods to exterminate the bacteria (Koene, et al 2015). Feels like an extraterrestrial lifeform in a science fiction movie.

Visual artist Janne van Gilst made an inventory of these ominous little bushes in Friesland, studied them, and made beautiful photographs, by using the blue cyanotype technique, of them (see below).

In order to replenish the livestock lost to the plague in the mid-eighteenth century, cattle were imported from northern Germany and, especially, from region Jutland in Denmark. Jutish cattle were crossed with the remaining stock in the northern Netherlands. Frisian farmers preferred black and white bulls for herd sires, which is how black colouring by and large replaced the original Friesian red colouring in the course of the eighteenth century. Despite the preference for black and white spotted markings, the recessive allele for red markings is still present in the breed (Stegenga 2008, McGuffey & Shirley 2011, Elischer 2014). This Friesian-Jutish crossbred forms the basis for the Friesian Holland breed that later would become the most successful dairy cattle in the world for a while. Province Noord Holland would imported much of its livestock from province Friesland and became an important dairy region of Friesian Holland cattle too. An estimated quarter of the cattle stock in province Noord Holland originated from province Friesland (Stegenga 2008).

In 1759, Eelko Alta, a minister from the small village of Boazum in province Friesland (on route the Frisia Coast Trail), developed a vaccine against cattle plague. At first, farmers were reluctant to vaccinate their cows -again a familiar reflex with new pandemics and its new cure- but after yet another outbreak of the plague in 1785, Alta’s vaccine proved to be both effective and harmless. The man of God was to be trusted after all. Do not think cattle plaque belongs to the past. As recently as 1996, the plague affected the European part of Turkey.

3. Herd Books

Until and including the nineteenth century, cross breeding and purity of a variety had never been an issue in the Netherlands. There were no specific breeds and the best way to describe the mish mash of cattle in this region was laaglandvee ‘low-country cattle’ (Theunissen, & Jansen 2020). At the end of the nineteenth century, however, things changed and breeding specific varieties or herds gained ground. No less than three herd books were established in the Netherlands in this period. A herd book is (of origin) a book containing the list and pedigrees of one or more herds of cattle. Herd book organisations determine the breed criteria of cattle which must be met in order to be accepted for registration in the book. Think of colour, patterns, size, measurements, shapes, origin etc.

For the Americans, who were from the mid of the nineteenth century very keen on importing dairy cattle from provinces Noord Holland and, especially, Friesland, being registered in the herd book was a prerequisite (Blokzijl 2012). Varietal purity of the breed was essential for the Americans. Between 1870 and 1880, in total 7,750 breeding cows were exported to America. Criticism of the herd books, therefore, was that they were too commercial. Merely an address book for the acquisitive Americans, instead of a means primarily to improve and guarantee the quality and purity of the national or, in the case of Friesland, provincial breeds.

Until the mid ‘70s, emphasis was always put on the exterior of cows. A beautiful cow was a good cow. A fashion model. Because performances of cows had fallen behind internationally by then, herd books adjusted their registration criteria in order to improve both quality, protein and fat, and quantity of the milk yield. No longer only care for the outside but also for the inside.

The initial three herd books in the Netherlands were: the Nederlandsch Rundvee-Stamboek (‘Netherlands cattle herd book’, abbr. NRS) founded in 1874, and the Friesch Rundvee-Stamboek (‘Friesian cattle herd book’, abbr. FRS), founded in 1879, and in the same year the Noord-Hollandsch Rundvee Stamboek (‘Noord Holland cattle herd book’). The Noord-Hollandsche Rundvee Stamboek of province Noord Holland was founded as a counter-reaction to the foundation of a separate Friesian cattle herd book in province Friesland. Applaud for the effort, but the Noord-Hollandsche Rundvee Stamboek was not viable and merged with the NRS in 1909 already. Mostly because cattle registered by the NRS and FRS were preferred by the Americans, who after all carried the moneybag. The best year ever of both the NRS and FRS was the year 1962. With 58,000 members, the NRS even was the biggest herd book of the world.

Noteworthy is that in 1904 the NRS decided to registrate only black and white Friesian Holland cows, because it would benefit the prices on the international market. So, no red-pied cattle anymore. The FRS was less definitive. Albeit black and white was also compulsory to be registered as Friesian Holland breed, a separate section of the herd book was opened (known as the hulpboek ‘help book’) for registration of different coloured cattle, which received the name Fries Roodbont ‘Friesian red-pied’. A breed now regarded as the authentic Friesian breed. The Fries Roodbont, also Roodbont Fries, constituted only a limited number. Only a few percent of the livestock registered in the FRS. To preserve the Roodbont Fries from extinction, in 1993 the Stichting Roodbont Fries Vee ‘foundation red-pied Friesian cattle’ was established. To date, about five-hundred Roodbont Fries cows exist.

With the developments of artificial insemination (AI), called kunstmatige inseminate (KI) in Dutch language, different AI foundations were formed. Artificial insemination techniques were developed in the ‘30s. It was veterinarian Jan Siebenga (1903-1987) from the hamlet of Soarremoarre in province Friesland, who stands at the basis of AI application in cattle breeding worldwide. In the ‘40s, America starts using AI. After the Second World War, AI is being used more and more in cattle breeding.

One of the effects of AI technology was that it accelerated the breeding process. No longer well-performing sires had to be transported from farm to farm to impregnate cows. With AI, not only could single doses of frozen semen of excellent sires impregnate innumerable cows, but also over the whole world. And within days, so to speak. One sire can have thousands of offspring. Bull Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell, for example, had a progeny of eighty-thousand. Injecting preferred quality semen in the total stock with a blink of an eye. Or, better, before you can say boo. Contrary to America, herd books and AI foundations in the Netherlands were merged and called syndicates. Therefore, the NRS changed into the Koninklijke Nederlandse Rundvee Syndicaat (‘royal Netherlands cattle syndicate’). In 1979, the FRS was renamed the Friese Rundvee Syndicaat (‘Friesian cattle syndicate’). Both consortia were still abbreviated as NRS and FRS.

If the reader wonders if there ever existed some form of animosity between the NRS and the FRS, the answer is: permanently. Imagine, Friesland the single province in the Netherlands that was too proud and stubborn to be part of the national herd book for dairy cattle. Moreover, the FRS refused to registrate cattle from outside the province, whilst the NRS, being national, accepted registries of cattle from province Friesland. For the Frisians it was, at the end, a Frisian breed.

In 1988, the NRS merged with Holland Genetics into -hold your breath- the Coöperatieve Rundveeverbeteringsorganisatie Delta (‘co-operative cattle-improvement organisation’, luckily shortened to CR Delta or CRV). A year later, in 1989, the FRS joined CR Delta. It was the end of the Alleingang of province Friesland.

Herds in the Netherlands, clockwise: Brandrood, Friesian Holland (HF), Roodbont Fries, Lakenvelder, Groningen Whitehead (G), Witrik, Meuse-Rhine-Yssel (MRIJ), Holstein Friesian (HF)

Soon after the introduction of the herd books, as from 1906, there were three categories of dairy cattle in the NRS and FRS. This were: the black and whites, or the Friesian Holland breed (abbr. FH); the red and whites, or the Meuse-Rhine-Yssel (abbr. MRIJ), and; the black and white Groninger Blaarkoppen, also Groningen Whiteheads. (abbr. G). The red and white Groninger Blaarkoppen were excluded for registration. By 1975, more than 70 percent of the stock in the Netherlands consisted of Friesian Holland, nearly 30 percent of Meuse-Rhine-Yssel, and 1 percent Groninger Blaarkop (literally ‘Groningen blister-head’). Besides the Friesian Holland, the Meuse-Rhine-Yssel and the Groninger Blaarkop, also herd books were introduced for the registration of the Roodbont Fries ‘red-pied Friesian’, the Lakervelder ‘sheet fielder’ and the Brandrood ‘fire-red’ breeds. The latter is a breeding direction of the Meuse-Rhine-Yssel.

Because the red and white Groninger Blaarkop was excluded from NRS registration in 1906, a separate herd book was founded for this variety, the Groninger Blaarkop Rundvee-Stamboek which only lasted until 1931. That year, the NRS decided to recognize the red and white Groninger Blaarkop after all.

Not an official breed but a so-called kleurslag ‘variety’, is the Witrik ‘white-person/one’ cattle. The Witrik is either a pale, red or black and white cow, whereby the belly is white, together with a white stripe on the back from head to tail. The head is pied. The same pattern of patches is also known in Belgium with the Belgisch Witblauw or, in English, Belgian Blue breed, and in Switzerland with the Braunvieh ‘brown cattle’.

To this day, there is still a herd book in particular for the original black and white Friesian Holland breed, called the Fries Hollands Rundvee Stamboek (‘Friesian Holland cattle herd book’, abbr. FHRS). As we shall see further below this post, the Friesian Holland, a breed that once ruled the world of dairy, has been marginalized since the mid ’70s of the last century, and is now an endangered breed. The FHRS is a small foundation with only 250 members. At the time of writing it exists forty years.

It is interesting to know that the distinction between breeds and varietal purity introduced in herd books during the second half of the nineteenth century, were based on the conviction that purity of race was a prerequisite to achieve the highest and continuous performance of domesticated animals. This conviction stemmed from the evolutionary theories on races that had emerged in the nineteenth century, and that also would find its way into the dark ideologies of colonialism and national socialism. Shortly below, we will see that the Nazi regime was highly interested in Friesian Holland cattle.

When in the early twentieth century it had become apparent that the herd books were too commercial orientated and too little on improving the purity of the herds, agricultural engineer Iman G.J. van der Bosch (1868-1948) was assigned by the ministry for agriculture to reorganize the herd books. It was Van der Bosch who introduced the three breeds: the black and white, the red and white, and the (black) Groninger Blaarkop in 1906. When evaluating the work of Van der Bosch today, it is clear that the seemingly sharp classification of herds, was and is a construct. In reality there always were, and are, varieties within the three categories. For example, the black and white cattle of Noord Holland was already different from that of Friesland (Theunissen & Jansen 2020). Indeed, race is but a construct. Reality is a dynamic continuum. A lesson that goes beyond animal breeds.

4. From Friesian Holland to Holstein Friesian

4.1. Friesian Holland Breed (FH)

This domestic breed, with its origins in the province of Friesland in the mid-eighteenth century, is officially registered as a breed from 1906 onwards. It has always been a so-called dubbeldoelkoe ‘dual purpose cow’, serving both for meat and milk production, although more emphasis has been placed on milk yield. It is important to note that almost all original Dutch cattle are dual purpose cows. The milk of the Friesian Holland cow has high fat and protein contents, which are necessary for the production of butter and cheese (Blokzijl 2012).

Friesian Holland cattle are described as strong and sober, with strong legs and toes, a good muscle mass ratio, a solid deep udder with well-shaped teats. As should be clear by now to the reader, Friesian Holland cattle are predominantly black and white coloured, although red-pied cows continue to be in small numbers.

World hegemony of the Friesian Holland breed as the best dairy cow, lasted from the end of the nineteenth centuries until more or less the mid ‘60s of the last century. During the ‘50s, the milk yield doubled in province Friesland. The yearly veekeuringen ‘livestock inspections’ in the month October in the city of Leeuwarden in Friesland were massive events. When all hotels were fully booked. Moreover, they attracted many foreign buyers. High quality Friesian Holland sires were sold to investors from all over the world, especially from America. But buyers came all the way from Japan and the Middle East too.

In 1959, the Shah of Persia (modern Iran), Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, visited farmer and artist widow Rigtje Boelstra on her farmstead Vijver Zathe ‘pond farm’ near the village of Jelsum in Friesland to buy her premium Holstein Friesians. Cattle from her stable was sold worldwide. Mohammad Reza Shah was accompanied by Queen Juliana and Prince Bernard. Rigtje Boelstra by then at the age of 76. Who knows, during the visit you could just hear in the back Elvis singing the Milkcow Blues Boogie on the radio. And who knows too, if Rigtje Boelstra would still be alive, she would have received a return invitation from the Shah and his wife Farah Diba to celebrate the 2,500 anniversary of Persia in Persepolis in 1971. Prince Bernard attended the festivities, which cost about 20 million USD back then.

Another special visit, much earlier though, was the one of General Botha, leader of the Boers against the English in South Africa. During his visit to the Netherlands in 1900, Botha also visited cattle breeders in the villages of Marssum and Âldtsjerk in Friesland.

A third remarkable visit we must mention is that of the regime of the Third Reich. During the Second World War, Nazi officials visited Friesland for its attributed pure Aryan race, culture and traditions, and for its famed cattle race. When Arthur Seyss-Inquart became Reichkommissar ‘governor’ of occupied Netherlands in 1940, he soon visited, together with Höhere SS- und Polizeiführer Hanns Albin Rauter, the dairy farm of Hendrik Oostenbrug near the village of Tytsjerk. Oostenbrug sympathized with the Nazi regime. But the worst was yet to come.

On August 1, 1940, one of the most murderous persons of human history ever, visited the same farm too. It was Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Warmly welcomed by Oostenbrug with coffee and a cookie. Among other, Himmler talked about Frisian farmer’s sons, who were looking for new land, to start farms elsewhere in the Nazi empire. This became a scheme promoted by yet another Frisian, Geert Ruiter from the village De Knipe in Friesland, who was Director-General for agriculture between 1941-1945. A scheme known as the Drang nach Osten ‘desire to the east’. For more see our post With the White Rabbit down the hole.

Let’s leave all these questionable visits of men in military uniforms behind us.

Although the first cracks in the superiority of Friesian Holland breed started to become visible in the course of the ‘50s already, it was the beginning of the ‘70s that the Friesian Holland breed definitively had lost its international position to the Holstein Friesian from America. Even cows in -the horror- province Noord Holland produced more milk than those in province Friesland in the meantime (Stegenga 2008). We said it before in this post, the moment you think you have achieved the highest, you are actually in a free fall already. Frisian farmers were big time.

Even successive reports of Dutch experts who made study visits to dairy farms in America in the years before, repeatedly marginalized and downgraded the performance of the Holstein Friesians. Deliberately ignoring evident improvements in milk yield. Frisian farmers simply were too conservative, and sticked to their good-looking, handsome cows. Dozed off by their tremendous success immediately after the Second World War. But gradually it became clear to foreign buyers that they bought a pig in poke: a beautiful shiny bull, but more and more failing to deliver a good performing progeny of dairy cows.

One of the earliest voices trying to wake up the sleeping beauties in province Friesland, was Rommert Politiek (1926-2014). But his warnings in the ’50s already were ignored for long. Politiek was a farmer’s son from the village of Wons in Friesland and a professor at Wageningen University and Research. He saw that the Friesian Holland breed got smaller in size. From about 134.5 centimetres at withers in 1947 to 131.5 centimetres in 1957. To quote Politiek in 1958:

Wanneer we zo doorgaan kunnen de koeien over enkele jaren onder m’n benen door.

Rommert Politiek, 1958

If we continue this way, within a few years the cows can pass under my legs

In addition, the daughters of sires performed less, and in general too little was done to improve the breed, according to Politiek. He was also of the strong opinion that Frisian farmers put far too much emphasis on the exterior of the cow (Blokzijl 2012), which was, of course, swearing in the Protestant church. Under Politiek’s leadership successful, experimental breeding programs were set up in the ‘70s to increase the amount of milk, and the fat and protein contents as well. Somewhat predictable, Friesian Holland cows crossed with Holstein Friesian cows did perform much better. Such a surprise.

Better to turn back half-way than to get lost altogether. When in 1974 the results became known of an international breeding program in Poland, the Friesian Holland cattle performed poorly. The Netherlands, mother country of the black and white dairy cow, ended in ninth place. Even Israel and New Zealand scored better. Of course, America came first. As a consequence of the low score, Dutch export of dairy cattle came to a sudden halt, hurting the pockets hard. Now, at a breakneck speed, the Friesian Holland stock was being replaced by Holstein Friesians. The so-called ‘Holsteinisation’ of the Dutch dairy herd (Theunissen & Jansen 2020). In 1975, the percentage of Holstein Friesian cattle of the total dairy livestock in the Netherlands was only 0.7. Twenty years later, the proportion was already 95 percent (Blokzijl 2012). Indeed, money talks, and time is money.

4.2. Holstein Friesian Breed (HF)

The Holstein Friesian is the dairy cow of the world. An American breed of primarily Frisian origin. Before we say something more about the Holstein Friesian cow, we first give an irresponsible short overview of the history of American dairy cattle in relation to the Netherlands, its main ancestry.

Coming to America

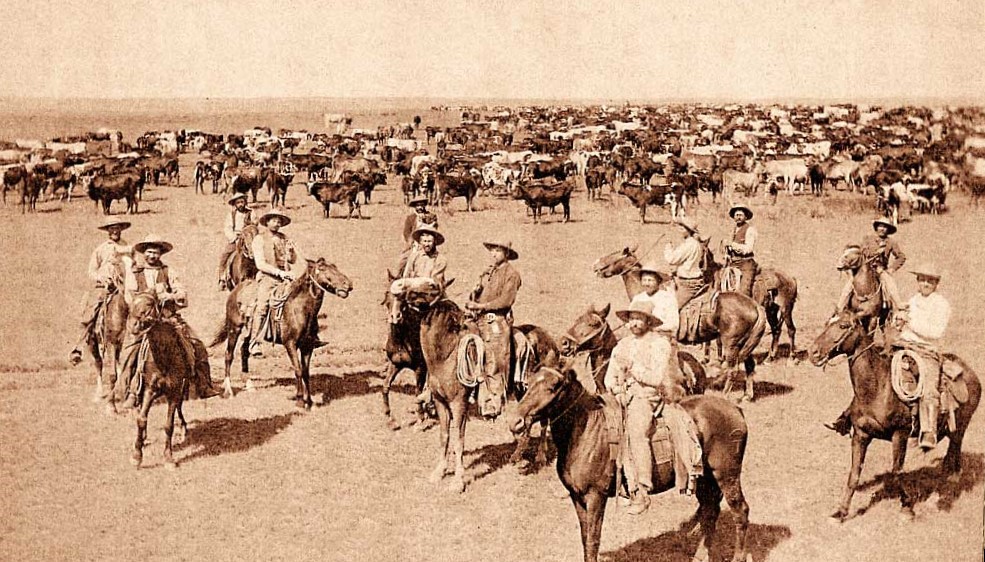

The history of cowboys and cattle in America starts when Europeans colonized the New World. Besides virtually exterminating the closest living thing to cattle, the Bison, Europeans started transporting cattle to America at the beginning of the seventeenth century. For both meat and dairy production purposes. It were all kinds of cattle breeds and varieties that were imported from the different European regions and countries.

The first documented undertaking of the Dutch to bring dairy cattle, and other livestock, into their young colony New Netherland was in 1625. Only a few years earlier, the Dutch had founded the town of New Amsterdam on Manhattan Island, the predecessor of New York City. The 1625 report mentions that the freighter of this so-called Animal Fleet of three ships was very content because only two cows died during the long sea voyage to America. It was a convoy of three ships of which two were reserved for livestock and all kinds of farm implements. Upon arrival, the cattle were brought to Noten Eylant ‘nuts island’ at first, what is modern Governors Island (combining nuts with governors, or vice versa, was not an option). Not much later, the cattle were transported to Manhattan Island. There, however, twenty head of cattle died. Again the cattle were relocated. Now to Fort Oranje ‘fort orange’, what is the modern city of Albany (Sypher 2016).

More imports of cattle and other livestock followed after the Animal Fleet of 1625. As a measure to facilitate and stimulate settlement of colonists, the Vereenigde Oostindische Company (‘united East-India company’, VOC) made transportation of cattle free of charge for private contractors called patroons ‘patrons’ in Dutch language. That cattle from the Dutch Republic were imported in relevant numbers, is also indicated when the English took control of parts of New Jersey in 1655. The English concluded that eastern New Jersey was already stocked with, among others, excellent cattle originating from the Netherlands and Sweden. It is also possible the English colonists in New Jersey acquired Dutch dairy cattle from the neighbouring colony New Netherland (Bowling 1942).

Willem Ysbrandtsz Bontekoe – Willem Ysbrandtsz (1587-1657) was born in the town of Hoorn in region Westfriesland in province Noord Holland, the Netherlands. Willem Ysbrandtsz was a skipper. In the year 1607, his ship the Bontekoe ‘pied-cow’ was captured at the Barbary Coast, modern coast of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, by pirates, and Willem Ysbrandtsz was enslaved (check our post Merciless medieval merchants to learn a bit more about the so-called white slave trade operated by the corsairs of north-western Africa). Willem Ysbrandtsz was very lucky to be bought free from the Barbary pirates.

In 1618, Willem Ysbrandtsz entered the service of the Vereenigde Oostindische Company (‘united East-India Company, abbr. VOC). His ship was named the Nieuw Hoorn ‘new Hoorn’. After having worked in the Indonesian archipelago, including a shipwreck, he was assigned to harass the Chinese Coast. After a biblical seven years of hardship and working for the VOC, Willem Ysbrandtsz returns to Hoorn, got married, and enjoys a quiet life.

Willem Ysbrandtsz wrote a detailed journal of his travels in the East. His journal formed the basis of the famous Dutch adventure book ‘De scheepsjongens van Bontekoe’ (‘the cabin boys of Bontekoe’) written by Johan Fabricius in 1924. About the three boys Padde, Hajo and Rolf sailing to the East. The book is published in English language under the title ‘Java Ho!: The Adventures of Three Boys Amid Fire, Storm and Shipwreck’. In the town of Hoorn, at 15 Veermanskade St., you can find find the house of Willem Ysbrandtsz, including the gable stone with the image of a bontekoe.

When hiking the Frisia Coast Trail, and you make a side trip to the North-Frisian rocky island of Helgoland at the North Sea, at Hafenstraße St. you can enjoy North Sea crab and beer at the local establishment Bunte Kuh. Indeed, the ship of the Westfrisian Willem Ysbrandtsz. Otherwise, when you are on the Wadden Sea island Langeoog in region Ostfriesland, you can have a meal at a restaurant named Bunte Kuh as well. What we are trying to say, everywhere along the southern North Sea coast the story of Bontekoe is known.

There are different theories about when the first Friesian Holland cattle set foot on American soil, but it must have happened at the beginning of the second half of the nineteenth century. According to some, the first cows arrived in 1852. It was Winthrop Chenery who had acquired a cow from a Dutch sailor. In the years 1857, 1859 and 1861, Chenery imported more cattle from the Netherlands and formed the first permanent herd. With some interruptions, imports continued until the ‘50s (Elischer 2014). According to others, the first Holstein Friesian cattle were imported in 1861 (Beal & Bakken 1997).

The denotation Holstein Friesian is a bit confusing. Why the cattle were labelled Holstein by the Americans anyway, is obscure (Strikwerda 1998, Stegenga 2008). Holstein is a region located in northern Germany, between the rivers Elbe and Eider. The Dutch, let alone the Frisians, never referred to their cattle as Holsteins, and the Americans did not specifically import dairy cattle from region Holstein. In fact, dairy cattle imported into America from the nineteenth century onwards, mainly originated from province Friesland and thus were of Friesian Holland stock (Strikwerda 1998). Probably, Americans were convinced that Holland Friesian cattle of provinces Noord Holland and Friesland, and of Oldenburg next to region Ostfriesland, were of Holstein ancestry. They initially seemed to have categorized all black and white dairy cattle along the marshlands of the Wadden Sea coast as one breed, naming it Holstein or Dutch (Chenery 1872).

Like in the Netherlands, the first American herd books were established at the end of the nineteenth century. The Association of Breeders of Thoroughbred Holstein Cattle was formed in 1871. A year later, the Dutch Friesian Cattle Breeders’ Association was established. A few more years later, in 1885, both herd books were merged into the Holstein-Friesian Association of America in the State of Vermont. Relatively recently, in 1994, the Holstein-Friesian Association of America changed its name into Holstein Association USA. Dropping the Friesian part of the name. Like dropping Nevis and continue with Saint Kitts. Frisian farmers and breeders feel hurt to this day. In the UK and Ireland, the name Friesian is still preferred to denote Holstein Friesian cattle.

The twentieth century

Imports of Friesian Holland cattle from provinces Friesland and Noord Holland temporarily came to a halt at the beginning of the twentieth century due to foot-and-mouth disease. The American dairy industry was forced to improve their dairy cattle on their own without importing bulls from province Friesland. During this period, the foundation was laid for the Holstein Friesian breed (Strikwerda 1998). Two bulls are the progenitors of the Holstein Friesian breed in America: Wisconsin Admiral Burke Lad, born in 1934, and Kol 2 Johanna Rag Apple Pabst, born in 1921. The female line of these sires originates from province Friesland, with the cow named Mercedes, and the male line from province Noord Holland, with the bull named Neptune (Strikwerda 2008). Currently, the whole Holstein Friesian dairy livestock in America descents from -again- two sires. They are named Round Oak Red Apple Elevation, and Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief (O’Hagan 2019).

Oh, and we have sent a request to all breeding farms in America to think of better names for bulls in the future.

Skalsumer Sunny Boy – This Holstein Friesian bull was born in 1985 near the village of Schalsum in province Friesland. Sunny Boy is responsible for two million doses of semen, and has an estimated progeny of 1.5 million dairy cows. It was a worthy competitor of the American bulls. Sunny Boy died in 1997. Sunny Boy was quite a character too. An unruly type. It had his own private stable and literally did not accept any stranger around him.

Americans, when compared to Europeans, always have had the gift of making real choices and to stick to them. After the Second World War, American breeders focussed their breeding programs on milk yield. Thereby making the Holstein Friesian breed no longer a true dual purpose cow. Improvement of the dairy breed was accelerated by AI techniques. Beef production was no longer relevant, neither how beautiful the cow looked like. Something Frisian farmers always had valued so much. Guess what, it became the strongest milk yielding cow the world has ever seen. From producing on average almost 2,500 kilograms of milk per year in the ‘50s, Holstein Friesian cows produce over 10,000 kilograms on average today. About 25 to 30 kilograms per day. You lose some, you win some. And counting. The aptly named cow Selz-Pralle Aftershock 3918 produced over 35,000 kilograms(!) of milk in 2017 (O’Hagan 2019).

Where will it end? With big data, genomic selection and algorithm selection the boundaries of milk production are being pushed further and further.

Holstein Friesian today

At present, there are about nine million dairy cows in America. With one exception, all of them are Holstein Friesian breed. Reckon circa 90 percent is Holstein Friesian. Other breeds in America are the Jersey originally from Britain, the Brown Swiss originally from Switzerland, the Guernsey originally from France, the Ayrshire originally from Scotland, and the Milking Shorthorns originally from England. Most breeds already present in America in the nineteenth century.

The Holstein Friesians produce about nine-tenths of all the milk in America. Hence the Holstein Friesian is the most recognized breed (Elischer 2014, O’Hagan 2019, Parrot-Scheffer 2023). But everywhere in the world you can find Holstein Friesians. “The Holstein-Friesian may be the single most important breed of cattle, not just dairy cattle, in the world” (Buchanan 2002). There is literally almost no country in the world where no Holstein Friesian cattle live. Eating grass, hay, concentrates, and yielding milk. Today in the Netherlands, the size of the dairy cattle stock is about 1.6 million heads. Nearly 20 percent is held in province Friesland (Van der Aa 2023). About 98 percent of the total dairy cattle stock in the Netherlands is Holstein Friesian breed.

The success of the Holstein Friesian breed is due to their milk yield. As said, over 10,000 kilograms milk on average every year. Compared to the Friesian Holland cow, the milk has lower fat and protein contents. Cow size and milk yield are related, and Holstein Friesians are very big cows. Their height at withers is between 155 and 185 centimetres and they weigh between 700 and 800 kilograms. That is considerably bigger than the Friesian Holland breed. Another crucial physical feature is the udder. These must, logically, be big too. Over the last fifty years, udders have been bred to become longer and wider, instead of deeper. Because then they would touch the ground too much, which can lead to infections (O’Hagan 2019). Udders were also bred in such a way they were more suitable for the milk machines.

Holstein Friesian cattle are predominantly black and white. Furthermore, as said, it is no longer a true dual purpose cow, like its immediate predecessor the Friesian Holland once was. Hence, the Holstein Friesian is less muscular up to the level of skinny. All its energy is put directly into milk production. Reason why Holstein Friesian cows need concentrate feed. It is because of this meagreness that farmers in province Friesland nicknamed the Holstein Friesians bonkerakken ‘bones racks’ (see also note 1). As a result, the beef is not of a very good quality either. As a side note; that the Ostfriesen ‘East Frisians’ in Germany sing nargens sünt die Kojen fetter ‘nowhere are the cows fatter’, it must be that they sing about the Friesian Holland cattle.

Lastly, the Holstein Friesian needs much care. Their high metabolic turnover makes them vulnerable to all kinds of production diseases (Mayne et al 2011). Everything resulting in growing expenses for the farmer and lesser animal welfare. An additional fragility of the Holstein Friesian breed is their extreme poor genetic variety, both male and female lineages. Basically, the breed is one huge inbred family. Inbred is affecting fertility rates as well (O’Hagan 2019). Another aspect is, that because more and more productivity is demanded from dairy cows, they burn out in a way. After a while, problems develop with legs and fertility. Some farmers return to a more robust and sober breed, like the Friesian Holland breed once was, also because they want to shift to a more durable way of husbandry (Blokzijl 2012).

5. Conclusion

Cradle of world’s most successful dairy cattle are the (former) marshlands of the Wadden Sea. These wetlands provided excellent breeding grounds for cattle, already for more than two-and-a-half millennia. Marsh cattle, as they have been called too (Chenery 1872). Clayish soils that are very fertile for grass which thrives on it. Cattle husbandry in this area started in the pre-Roman Iron Age already. Cows were kept for meat, hides and dairy, and oxen used as beast of burden.

With the arrival of the Romans in the first century AD, dairy production became a more prominent part of the husbandry. From the High Middle Ages, due to the embankment of the Wadden Sea coast with higher dykes, the quality land improved and became even more productive. Only in province Friesland, an estimated 14.000 longhouses existed, with dairy production as their main economic activity. From the late sixteenth century, dairy farming evolved and became a major profitably business. The Dutch exported the new dairy production concept along the southern coast of the North Sea.

From the mid-eighteenth century, the Friesian Holland breed developed in the northern Netherlands. The classic black and whites, albeit with the relativisation that a clear division between breeds and varieties was not yet the case. Cross-breeding was widely practised. A century later, Americans started to import dairy cattle from Noord Holland and, especially, Friesland. In the 1950s, province Friesland is the centre of the world for the best dairy cattle.

But the Americans catch up. Out of the Friesian Holland breed they bred the Holstein Friesian. A cow with a far better milk yield. Frisian farmers tried to ignore their defeat at first. But when in the mid ‘70s export of their cattle comes to a complete standstill, they quickly switch to the Holstein Friesian. Like the rest of the world was already doing for a decade. In the meantime, Holstein Friesian bulls bred in province Friesland can compete with bulls from America again. The question is, however, what course will the Frisian breeders and farmers take? That of mass production or of sustainability?

The Holstein Friesian has become a tall and meagre cow on long skinny legs, and with a big bursting udder. The Golden Calf of the dairy industry worldwide. According to Frisians, who did prefer the more voluptuous and muscular body of their own Friesian Holland cows, these Holstein Friesian cows are nothing more than bonkerakken, racks of bones. Whilst Americans in contrast consider them ‘feminine and refined’. Who knows, an indirect effect of the models of Victoria Secret. The only one way to settle this dispute:

Mirror mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?

Note 1 – That a beautiful appearance was an indication for quality according to farmers in Friesland, is something one of the Frisian bastards was taught when he was a little boy and stayed at his grandfather’s and -mother’s farm at Langezwaag. One day, somewhere in the ‘70s, he walked into the lands with his father. It was springtime and several youngsters, i.e. young cattle, were in the fields. Drawing an imaginary line with his finger, the bastard’s father explained that one of the youngster was a fine bull because its back was very straight. The bastard’s father often said those Holstein Friesians basically were a bonkerak ‘bones-rack’.

When the Holstein Friesian bull Ivanhoe Sevens was imported from America in the ‘70s and pictures of it were spread, Frisians spoke disapprovingly about the animal. This because it had a dented back. Later, when Ivanhoe Sevens’ offspring turned out to be excellent dairy cows, Frisian farmers spoke a bit milder about the bull (Strikwerda 2008): “It koe minder” (‘it could have been less’)

By the way, the photograph with the woman with a handkerchief over her head milking a cow by hand and sitting on a stool, is the bastard’s grandmother.

Note 2 – The Never-ending Experimental Agricultural Policy

Nobody denies anymore that both the Dutch and European agricultural policy is basically a chain of experiments resulting in a long-term yo-yo policy, which in itself is a contradictio in terminis. The definition of policy is prudence and a stable course of action. After the Second World War, it was farmer and resistance hero Sicco Mansholt (1908-1995) from the village of Ulrum in the north of province Groningen who became Minister of Agriculture in 1945 for the Labour Party. He would be secretary in several cabinets until 1956. In 1958, Sicco Mansholt became Commissioner of Agriculture of the European Commission, and in 1972 he even became President of the European Commission. Mansholt, therefore, has been one of the very influential European politicians.

Mansholt’s policy was based on the adages ‘never to suffer hunger again’ and ‘more cows per farmer’. His policy was an answer to the hunger during the war and the economic crisis before that. It stimulated mass production through economies of scale to meet the growing food demand. Mansholt also became the architect of the Common Agricultural Policy of the EU.

In the Netherlands, systematic ruilverkaveling ‘re-allotment of land’ meant an end to small plots of land. Little farmers and gardeniers ‘small farmers living from potatoes’ were pushed out, and many emigrated to Canada and the US (Betten 2014). In addition, groundwater levels were lowered for the purpose of making it suitable for heavy machines. In the ’60s, farmers protested massively against the agricultural policy forcing farmers to increase the number of cattle. A farm should have between forty and sixty cows (Strikwerda 1998). Anyway, thanks to Mansholt’s policy, the tiny Netherlands became one of the biggest food-producing countries in the world. Concerning livestock, it ranks number one in the world when you set the number of animals against the size of the country. As a secondary effect of Mansholt’s policy, many of the historic patterns and forms in the Dutch landscape have been erased and turned into a sterile, green billiard cloth.

The downside of this production policy became visible in the ’60s. In the Netherlands, seas of milk, mountains of butter, grain supplies, and low prices were the result. Massive overproduction. In the early ’70s, farmers should reduce their production, while only a decade before they had to scale up. In the Netherlands, government-supported marketing stimulated the consumption of milk. The EU even heavily subsidized school milk (Veltman 2007). Many second generation children are familiar with advertising slogans like: met melk meer mans ‘with milk more man/capable’, melk is goed voor elk ‘milk is good for everyone’, melk de witte motor ‘milk the white engine’, al het goede komt van Melkunie-koeien ‘all good comes from Melkunie cows’, melk moet, melk doet je goed ‘milk should, milk does you good’, melk, de grootste ontdekking van de mond ‘milk, de biggest discovery of the mouth’, etc. But that was not all.

It also became evident that the natural environment had suffered too much. The report of the Club of Rome ‘The Limits to Growth’ published in 1972, in which the Club warned that continuous growth was a dead end, meant a wake-up call. Unchecked consumption could crater the world economy by the year 2100. The conclusions made a deep impression worldwide. At the end of the ’80s, the Dutch government decided to reduce ammonia discharge and imposed quotas on manure processing and fertilization of land. A decade later, farmers had to confine their cattle indoors to protect the environment (Stegenga 2008).

After, among others, the report of the Club of Rome, Sicco Mansholt started to regret his national and European policies of mass production over the last decades. From the mid-’70s onward, Sicco Mansholt advocated for a sustainable agricultural policy instead. To consider the consequences of agriculture on water, soil, and air. The three preconditions for viable agriculture itself. Something the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union had not done until the ’80s. It had not even mentioned the word “milieu” once all that time (Bleumink & Riele 2016).

At the time of writing, we have seventy-six years and three months left before the clock strikes 00:00 and doomsday January 1, 2100 begins. Will the agricultural yo-yo policy come to an end before that?

Note 3 – In this post we let the history start around 600 BC. Of course, the history of tamed cattle is much older. Domestication of wild aurochs started around 7,000 BC, in the vicinities of both modern countries Pakistan and Turkey (McTavish, et al 2012), and milk fats have been found in Turkey near the Sea of Marmara in the same period. Around 5,000 BC, domestic cattle shows up in the area of the southern coast of the North Sea.

Drinking milk requires a genetic constitution of being lactose tolerant. Most people on the planet are, in fact, lactose intolerant. When the genetic mutation of tolerance appeared, these people had an advantage. This genetic mutation appears around the same time when nomadic pastoralism appeared, i.e., moving from one place to another with your cattle and sheep for new pastures (Pront & McMarron, 2023).

We wonder: is the ancient union of humans and cattle the reason why natural cow dung does not smell badly, whilst pig and chicken dung does? For millennia our ancestors slept next to it, even on it, used it as fuel, and needed it for fertilizing land to grow grass and crops. Dung was crucial for survival. Is it in our genes perhaps? Now the reader also understands the historic context of the English expression ‘the shit’ for best quality.

Note 4 – For more blogposts about animals of the Frisia Coast Trail area, tap the tag ‘animals’

Suggested music

- Elvis Presley, Milk Cow Boogie (1955)

- Aerosmith, Milk Cow Blues (1977)

- Pulcino Pio, The Little Chick Cheep (2012)

Further reading

- Aa, van der H., Utrecht enige provincie waar de melkveestapel groeit (2023)

- All About Bison, Cattle History in North America (website)

- Barnes, M.S., Sounds of Success: Can Music Enhance Milk Production in Dairy Cows? (2023)

- Beal, G.M. & Bakken, H.H., Fluid Milk Marketing (1997)

- Betten, E., Terpen- en wierdenland (2014)

- Bleumink, H. & Riele, te H., Historische lijnen en de mestdialoog (2016)

- Blokzijl, M., De laatste Friese koe (2012)

- Boer, de M., Rommert Politiek: rêder fan de Fryske boer en ko. ‘Neat praktysker as in goeie teory’ (2011)

- Borghaerts, P. Houtstromen. Bossen, binten en boerderijen (2021)

- Bouwman, W., Hier gebeurde het: Heinrich Himmler op bezoek in Tytsjerk (2015)

- Bowling, G.A., The Introduction of Cattle into Colonial North America (1942)

- Buchanan, D.S., Animals that produce dairy foods. Major Bos taurus Breeds (2002)

- Burgers, R., Meer geiten en schapen en minder koeien in Noord-Nederland (2019)

- Campbell, J. & Cousineau, P., The Hero’s Journey. Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work (1990)

- Chenery, W.W., Holstein Herd Book. Holstein Cattle in the United States. Also a sketch of the Holstein Race of Cattle (1872)

- Darwin, C., On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1859)

- Elischer, M., History of dairy cow breeds: Holstein (2014)

- Fabricius, J., De scheepsjongens van de Bontekoe (1924)

- Gilst, van J., Miltvuurbosjes (exposition at Lage Noorden, Hallum) (2021)

- Haan, de H. & Vaart, van der J.H.P., Amerikaanse boerderijen in Fryslân. Inspiratiebronnen, bouwers en modellen (2021)

- Haan, de P., De veepestregisters uit 1745 van Westdongeradeel (2008)

- Hindley, J., Does a Cow Say Boo? (2002)

- Historiek, Het Gouden Kalf. Herkomst en betekenis (2021)

- Huisman, K. & Strikwerda, R., Internationale belangstelling voor topstieren (2011)

- Hullegie, A. & Prummel, W., Dieren op en rond de Achlumer terp (2015)

- Kolkman, I., Calving problems and calving ability in the phenotypically double muscled Belgian Blue breed (2010)

- Koene, M.G.J., Rosa, de M., Spierenburg, M.A.H., Jacobi, A. & Roest, H.I.J., Een oude bekende: Miltvuur in Nederland (2015)

- Kuiken, K., Boelstra, Rigtje (1883-1969) (2019)

- Landwirtschaftlicher Hauptverein für Ostfriesland e.V., Landwirtschaft in Ostfriesland (website)

- Lasance, A. (transl.), Wizo van Vlaanderen. Itinerarium Fresiae of een rondreis door de Lage Landen (2012)

- Lauwerier, R.C.G.M, Hoornloze runderen in de Romeinse tijd (2012)

- Lauwerier, R.C.G.M. & Laarman, F.J., Hornless (polled) cattle in the Netherlands: a Roman-period phenomenon (2012)

- Levende Have, Runderen soort en geschiedenis (website)

- Looijenga, A., Popkema, A. & Slofstra, B., Een meelijwekkend volk. Vreemden over Friezen van de oudheid tot de kerstening (2017)

- Mayne, S., McCaughey, J. & Ferris, C., Dairy Farm Management Systems. Non-Seasonal, Pasture-Based Milk Production Systems in Western Europe (2011)

- McGuffey, R.K. & Shirley, J.E., Introduction, History of Dairy Farming (2011)

- McTavish, E.J., Decker, J.E., Schnabel, R.D. & Hillis, D.M., New World cattle show ancestry from multiple independent domestication events (2013)

- Melkveebedrijf, Hoe kwam de eerste Holsteinstier in Europa? (2020)

- Miltenburg, H. & Strikwerda, R., Cows in the picture. The cow presented on 200 historical postcards (2017)

- Mons, G., Onafhankelijk alternatief. Stamboek FHRS bestaat 30 jaar (2013)

- Nieuwhof, A., Dagelijks leven op terpen en wierden (2018)

- Nijdam, J.A., ‘De gemaskerde Wizo: vervalsing, mystificatie of pastiche?’. Bespreking van: Wizo van Vlaanderen, Itinerarium Fresiae (2012)

- NordGen, Jutland Cattle (website)

- O’Hagan, M., From Two Bulls, Nine Million Dairy Cows (2019)

- Overbye, S. & Petersen, J., Ga mee naar het duurste feest ooit (2023)

- Parrott-Scheffer, C., Holstein-Friesian breed of cattle (2023)

- Pront, M. & McMarron, M., Waarom zijn we ooit koemelk gaan drinken? (2023)

- Prummel, W. & Kückelmann, H.C., The use of animals in settlements on the Dutch and German Wadden Sea Coast, 600 BC-AD 1500 (2022)

- Raffied, B., The slave markets of the Viking world: comparative perspectives on an ‘invisible archaeology’ (2019)

- Roy’s Farm, Holstein Friesian Cattle: Uses & Best 23 Facts and Tips (website)

- Sijens, D., Friese bewegers: Geert Ruiter. Pleiter foar boerebelangen yn it ferkearde tiidrek (2016)

- Stegenga, W., De Friese koe. Een geschiedenis in woord en beeld (2008)

- Stichting Roodbont Fries Vee, Geschiedenis van het Roodbonte Friese Vee (website)

- Stichting Zeldzame Huisdierrassen, Runderen (website)

- Strikwerda, R., Boijen de Boer brak door met Holsteinkoe (2011)

- Strikwerda, R., Friese zwartbonte koeien: eens aanbeden, nu zeldzaam (2011)

- Strikwerda, R., Melkweg 2000 (1998)

- Strikwerda, R., Nederlands rundvee liet in 1913 nieuwe kansen zien (2013)

- Sypher, F.J., The Animal Fleet to New Netherland (2016)

- The Cattle Site, Friesian (2022)

- Theunissen, B. & Jansen, I., Hoe de Nederlandse melkveerassen ontstonden en wat dat betekent voor hun behoud als levend erfgoed (2020)

- Toneelgroep Jan Vos, Mansholt in reprise! (play) (2021)

- Veldstra, G., Herre uit Elahuizen is voor de vierde keer de beste veebeoordelaar van Nederland. ‘Jo binne in koweman of net’ (2023)

- Veltman, F., Melk, de witte motor (2007)

- Weimar, M.R. & Blayney, D.P., Landmarks in the U.S. Dairy Industry (1994)

- Windig, J.J., Hoving-Bolink. R.A. & Veerkamp, R.F., Breeding for polledness in Holstein cattle (2015)