Close to a terp named Fallward near the village of Wremen in Land Wursten, archaeologists discovered a unique site offering a rare glimpse into the world of the Migration Period. A view into the world of the Old Saxons who lived on the tidal marshlands of the Wadden Sea at the mouth of the River Weser. At the terp of Fallward, two gravefields from the beginning of the fourth until the late fifth centuries were unearthed, containing spectacular wooden finds. This is due to the excellent preservation conditions of the oxygen-depleted clay soil. One of the finds is what became known as Thron der Marsch (‘Throne of the Marsh’). But there is much more exciting stuff!

For several reasons, the Fallward excavations are relevant to the coastal early history of the wider region. The most important reasons are:

Firstly, the burials and artifacts date from the Migration Period. This great wandering of peoples started in this edge of the world when the Roman Empire began to crumble from the fourth century onward, and lasted until the Early Middle Ages when things more or less had settled again.

Secondly, the importance of this area. Already during the Roman Period, this area in north-western Germany, known as the Elbe-Weser triangle, was centrally located. Access to the hinterland via rivers and to Scandinavia and the British Isles via the sea. This continued to be the case during the Migration Period. Many valuable imported objects have been found in the River Weser estuary, including fourteen gold bracteates originating from southern Scandinavia (Aufderhaar 2017).

Everything indicates that the people in the triangle were connected to a wider, supra-regional elite network. The marshes of Land Wursten, where a series of nine terps (i.e. artificial dwelling mounds) was erected from the first century AD onward, might be part of a central place. These were from south to north: Weddewarden, Imsum (formerly Dingen), Barward, Fallward, Wremen, Feddersen, Mulsum, Dorum, and Alsum. Not much later, the Westergo region in the northwest of the province of Friesland and the area at the mouth of the River Rhine in the province of Zuid Holland would also become such central places of power in Frisia.

There are many more terps, locally called Wurten, in Land Wursten. Perhaps about 400 terps. Both dwelling mounds and refuge mounds for livestock called a Hofwurt. The region’s name Land Wursten derives from Land der Wurten (Wremer Chronik 2014).

Thirdly, the artifacts belong to a people who were responsible for much of the migration in the North Sea area during the Migration Period. It was the Saxons, also referred to as Continental Saxons or Old Saxons, from specifically this region who migrated west in significant numbers. From the second quarter of the fourth century, they repopulated the near-empty tidal marshlands of the original Frisians (i.e. Frisii) and the Chauci and settled in England, creating the Anglo-Saxon world. Indeed, the adventus saxonum ‘coming of the Saxons’, and a demonstration not only wisdom comes from the East. Therefore, the maritime Old Saxons, new Frisians, and new Anglo-Saxons were very closely related still during this period. For more in depth information about the origins of the Frisians read our post Have a Frisians Cocktail!

The Romans also spoke of the Ingaevones, referring to the peoples of the southern North Sea area. The languages these tribes spoke were very similar and termed as North Sea Germanic or Ingvaeonic. It is certain that the Saxons of the tidal marshes of the Wadden Sea did not speak Old Saxon but an “undifferentiated West Germanic” language, probably with the presence of the Roman culture and Latin language in the area (Ludwig 2022). As we will see later in this post, the grave gifts also reveal Roman influence on the material culture (Schöne 2006). Frisians, Anglo-Saxons, and to a somewhat lesser extent, Saxons spoke the same language within a continuum of dialects.

The Migration Period and the beginning of the Early Middle Ages, the southern North Sea coast area must be viewed as a “dynamic cultural system that makes sense in its own right and operated largely outside the homogenizing tendencies of major political centers of power” (Deckers 2017) like the Merovingian kingdoms. Only from around the eighth century distinct languages emerged in this maritime space spanning from England to Flanders up along the coasts of the Netherlands and Germany to southwestern Jutland.

In other words, when picturing the people living in the River Weser estuary in the fourth and fifth centuries, part of the Elbe-Weser triangle, it is like picturing the first Saxon migrants or new Frisians colonizing the nearly empty marshlands of the Old Frisians (i.e. Frisii) after the habitation hiatus of the coastal area in the Netherlands between roughly AD 325-425. In addition, some historians suggest that it was through this area from the Danish peninsula that the runic script was spread further west to Frisia and England (Düwel & Nedoma 2023).

To illustrate the dynamic maritime culture and long-standing kinship between the Frisians and the Saxons, Land Wursten culturally changed from Saxon to Frisian during the Early Middle Ages. The people became known as Wurstfriesen and spoke a variant of the Frisian language. At the end of the Early Modern Period, however, Land Wursten, together with the province of Groningen and the region of Ostfriesland, linguistically switched from the Frisian to the Low Saxon language, also known as Platt. Today, the German language is dominant and Platt is increasingly in dire straits. Learn more about Land Wursten in our post Joan of Arc an inspiration for Land Wursten.

grave of Der Bootsmann and artifacts from the Wurt Fallward excavations, 4th and 5th century

The Fallward excavations

The excavations near the Fallward terp, as said called a Wurt locally, were carried out between 1993 and 1998. Two gravefields were unearthed and encompassed in total 260 burials. Mostly cremations but also with about 60 inhumations that are responsible for the unique (wooden) artifacts. Mixed burial practices are typical of the funeral tradition of the coastal area of the southern North Sea, until Christian customs replace the pagan ones at the end of the Early Middle Ages. Christianity prescribed the body was buried and not cremated, and without grave gifts.

In his work Germania, the Roman historian and politician Tacitus writes about the Germanic tribes in the north:

Statim e somno, quem plerumque in diem extrahunt, lavantur, saepius calida, ut apud quos plurimum hiems occupat. Lauti cibum capiunt: Separatae singulis sedes et sua cuique mensa. Tum ad negotia nec minus saepe ad convivia procedunt armati. Diem noctemque continuare potando nulli probrum. Crebrae, ut inter vinolentos, rixae raro conviciis, saepius caede et vulneribus transiguntur.

Book Germania, paragraph 22, by Tacitus (AD 56-120)

Immediately after sleep, which they normally extend into the day, they wash themselves, usually with warm water because it is often winter for them. After washing, they eat: everyone has their own chair and table. Then they leave armed for business, but no less often to banquets. Drinking all day and night is not a shame for anyone. As often happens with drunkards, violent quarrels take place, rarely ending in swearing, but more often in murder and bloodshed.

Besides the fact that alcohol abuse was apparently quite a social issue, even for the Romans to be noticed, Tacitus describes that everyone had their own seat and table. In the grave of a little girl, baptized Frauke by the researchers, a fully preserved stool and a small table, both with turned wooden legs, have been excavated (see image). Although his writings are two centuries older, this seems to confirm what Tacitus wrote, that everyone had their own chair and table.

The girl was 3 or 4 years old and lived in the first half of the fourth century and was buried with much care and affection during summer. She was buried in a used wooden trough and the grave was covered with hay. Moreover, the grave was encircled by a ditch with a diameter of 8 meters. Inside the grave a long, thin hazel wood rod was ritually placed. The hazel was ascribed protective power (Peek et al 2022). Furthermore, the little girl wore a woollen dress adorned with fibulas. In addition to the furniture placed in the girl’s grave, the table and stool, also some of her toys were given. Lastly, some ceramics, a worked wooden bowl and a casket of maple wood were part of the grave gifts.

Another grave is that of a woman aged between 45 and 55, which was a respectable age back then. She wore jewellery like finger rings, a bronze hairpin, a silver fibula, and two tutulus fibulas, i.e., conical-shaped brooches, as well as a necklace of glass beads. She also wore leather shoes. The woman’s body was wrapped in leather and was laid on an oak plank with cushions made of reed. Part of the grave gifts was a wooden vessel with a beautiful round-turned lid, two bowls, and pottery. Besides these utensils, again thin rods of hazel wood were also ritually placed in the grave.

A third noticeable grave is that of a little girl of about one and a half years old, dated to the first half of the fifth century. The girl wore woollen clothes, silver-plated fibulas, and glass beads. She was buried in an old trough, together with a hazel wood rod, and, above all, covered with flowers. Flowers included clover, red bartsia, and autumn hawkbit, among others. The grief of the family members is almost tangible.

After these female graves an interesting male grave. It is the grave of a man approximately 40 years old, dated between 405-422. He was laid on a bed of reed and buried together with a longbow made of hazel wood and several arrows. Curiously, the bow lacked the tendon, and the arrows lacked iron heads. In fact, they were never used.

Boat graves

Very special finds of the Wurt Fallward excavations are two boat graves. We all know these from Scandinavia and, of course, from the area of Sutton Hoo on the south-eastern coast of England. Often, ship burials are associated with Vikings, but it is an older and broader material culture. As is demonstrated again with these two burials.

One boat grave consists of a female buried in a dugout canoe dated to the first quarter of the fifth century. She was laid on a bed of hay too. Grave gifts were a stool and two wooden bowls. The other, more striking boat grave was located at the border of the grave field and contained the biggest inventory of grave gifts. It is the grave of a male – who was named Heinrich by the researchers – also dated to the mid-fifth century (Schön 2006, Peek et al 2022).

The second boat grave is again a dugout canoe. An almost 4.5-meter-long canoe made of oak wood. The boat grave was covered with wooden planks placed at an upward angle, thus creating a space or chamber (see image). A very similar, modest, boat grave had been found at Solleveld, in the old dunes just south of the city of The Hague in the province of Zuid Holland, which was then still Frisian territory. The Solleveld boat grave is considerably younger and dated to the first half of the seventh century. Check out our post “Rowing souls of the dead to Britain: the ferryman of Solleveld”.

Part of the inventory of the male’s boat grave was again a personal table made of field maple with turned wooden legs, just like in the young girl’s grave described above. Furthermore, a bowl made of sycamore and a vessel made of alder wood in the shape of a bird, perhaps a pelican (see image), were found. But there was even more stunning stuff in this second boat grave.

Know that these dugout canoes correspond with the description the Roman writer Pliny gave in his book Naturalis Historia of the vessels of the pirates living along the North Sea coast in the first century AD (Looijenga et al 2017).

Throne of the Marsh

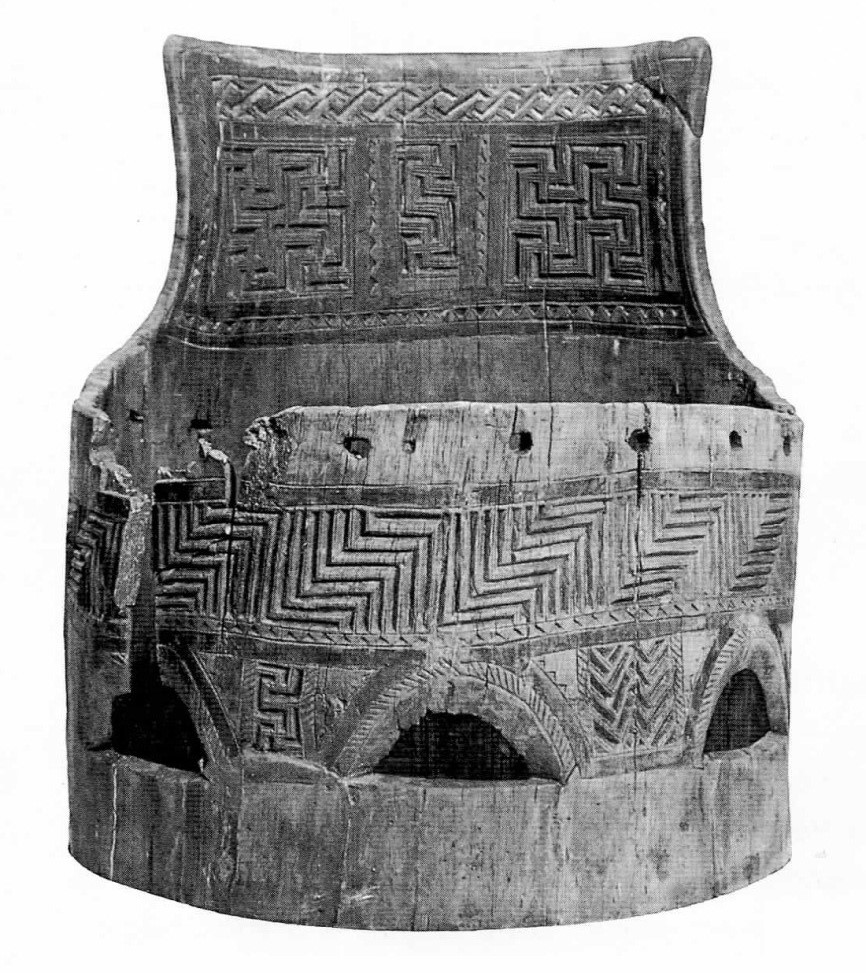

Finally, the Throne of the Marsh. A grave gift, part of the second boat grave. The throne is actually a state chair or Prunkstuhl, and is dated around the year 420. It is 65 centimeters high and dug out in one piece from an alder tree log, also called a block chair or Klotzstuhl in the German language. The chair is richly decorated with carved geometric patterns.

footstool Wurt Fallward, ca. AD 420

In addition to the block chair, a wooden footstool has been preserved from the same grave. On the side of the footstool, the following mirrored runic text is carved into the wood: ᚲᛋᚫᛗᛖᛚᛚᚫ ᛚXᚢᛋᚲᚫᚦI and reads ksamella lguskaþi. The first word must be read as scamella, from scamnum which is Vulgar Latin for ‘bench’. The second word literally means ‘deer/elk-damage’ (Theune-Grosskopf & Nedoma 2006). On the backside of the footstool, an image of a deer or elk being killed by a dog is depicted. In other words, with the ‘a’ transferred from the end of the first word to the beginning of the second word (Ludwig 2022), the runic inscription reads skamell alguskaþi which means ‘The Deer Hunter’. Representations of hunting dogs are well-known from (Late) Roman artifacts (Schön 2006).

The term ‘throne’ is a bit too much. We wouldn’t dare to contest the true king of the marsh, King Alfred the Great of the West Saxons. Nevertheless, a block chair must have belonged to a person of stature (Haio Zimmermann 2015). Age of the male is estimated around 50. The additional silver-plated fittings of a Roman belt which was part of the grave gifts, suggest that the man had served as a mercenary in the Roman army before, for example, stationed in northern Gaul. Being a veteran of the Roman army, he enjoyed respect and had gathered wealth (Hansen 2010, Peek et al 2022). Was his name Alguskaþi then? Or was that just the name of his loyal and watchful dog who always would lay at his feet while the elder grey-haired man sat on his chair orating ad nauseam about his past battle adventures? Knowing how important dogs were during the Late Iron Age until the Early Middle Ages.

By the way, the tradition of block chairs continued in remoted Scandinavia well into modern times. It was the seat of the master of the house, while the other family members had to sit on modest chairs. We did not made it up.

Since it is really the same region and era, we must mention King Finn Folcwald. He was a king of Frisia around the year 450 and is mentioned in several early medieval texts, including the epic poem Beowulf. Where his citadel was, is a big question mark to this date. But with the block chair of Folcwald (not Fallward!), we can imagine how the throne he sat on could have looked like. For more about King Finn, and how he was betrayed and killed, read our blog post Tolkien pleaded in favour of King Finn.

Note 1 – The etymology of Fallward, albeit we haven’t found any article on it, might be the terp or Wurt of a person named Falco, Falke, Folc or Folko. Placenames with the suffix -wurt, -ward, -warden, -werd, -wurd, etc., dating to the Middle Ages, are typical for the Wadden Sea coastal area and are often combined with the name of the person (and kin) who once inhabited the artificial settlement mound. There are so many village names ending with -wurd, etc. in the area that you tend to think people did not have a lot of imagination and creativity back then. Or was ‘me, myself and I’ always the dominant culture? Anyways, Falco’s Wurt or Folc’s Ward might be an explanation. Coming close to Folcwald but just not.

Note 2 – The Wurt Fallward excavations are comparable to the Feddersen Wierde (another local term for ‘terp’) excavation 2.5 kilometers north of Wurt Fallward. At Feddersen Wierde, a complete terp settlement has been excavated. It dates from the same era as Wurt Fallward. One of the buildings at Fedderson Wierde has been identified as a hall or Herrenhof der Sitz, the seat of a local ruler (Peek et al 2022).

Note 3 – Featured image: The lighthouse Der Kleine Preuße ‘the little Prussian’ at the marsh near the village of Wremem in Land Wursten.

Suggested music

- Stanley Meyers, Cavatina, theme movie The Deer Hunter (1970)

- Bob Dylan, Hazel (1973)

Further reading

- Aufderhaar, I., Between Sievern and Gudendorf. Enclosed sites in the north-western Elbe-Weser triangle and their significance in respect of society, communication and migration during the Roman Iron Age and Migration Period (2017)

- Both, F., Jausch, D. & Peters, H.G. (eds.), Archäologie Land Nedersachsen. 25 Jahre Denkmalschutzgesetz. 400.000 Jahre Geschichte; Schön, M.D., Gräber des 4. und 5. Jh.s in der Marsch der Unterweser an der Fallward bei Wremen, Ldkr. Cuxhaven (2006)

- Brooks, S., Boat-rivets in Graves in pre-Viking Kent: Reassessing Anglo-Saxon Boat-burial Traditions (2007)

- Deckers, P., Cultural Convergence in a Maritime Context. Language and material culture as parallel phenomena in the early-medieval southern North Sea region (2017)

- Düwel, K. & Nedoma, R., Runenkunde (2023)

- Haio Zimmermann, W., Miszellen zu einer Archäologie des Wohnens (2015)

- Hansen, S., Archäologische Funde aus Deutschland (2010)

- Hunink, V. (transl.), Tacitus. In moerassen & donkere wouden. De Romeinen in Germania (2015)

- Lanting, J.N. & Plicht, van der J., De 14C-chronologie van de Nederlandse pre- en protohistorie VI: Romeinse tijd en Merovingische periode, Deel A: Historische bronnen en chronologisch schema (2010)

- Looijenga, T., Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions (2003)

- Looijenga, A, Popkema, A. & Slofstra, B., Een meelijwekkend volk. Vreemden over Friezen van de oudheid tot de kerstening (2017)

- Ludwig, R., Did the Saxons really speak Saxon (in the 5th century)? (2022)

- Nösler, D., Fibeln als Werkzeug Die Verwendung von Fibeln zur Verzierung völkerwanderungszeitlicher Keramik in Niedersachsen (2018)

- Peek, C., Hüser, A. & Meier, U.M., Die Gräber der Fallward. Ausstellung im Museum Burg Bederkesa (2022)

- Schulze-Forster, J., Möbel der Römischen Kaiserzeit aus Wehlitz, Lkr. Nordsachsen (2008)

- Theune-Grosskopf, B. & Nedoma, R., Ein Holzstuhl mit Runeninschrift aus dem frühmittelalterlichen Gräberfeld von Trossingen (2006)

- Wremer Chronik, Land der Wurten zwischen Weser und Elbe (2014)