The arrival of the Romans in northwest Europe at the beginning of the era, with the river Rhine as frontier, was the starting signal for five centuries of widespread piracy. Piracy not only affected the coasts of Britannia and Gaul, but also stirred things up as far as the coast of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. The heartland of these pirates was the coastal area north of the river Rhine up to the river Elbe, including parts of the adjacent interior. It was a dangerous coast that even sheltered notorious capers until the late fourteenth century. Out of this long-standing raiding tradition, a common culture with a common language evolved, encompassing the southern coast of the North Sea and both sides of the English Channel. This pirate culture, which flourished in the course of the fifth century, is, in fact, partly the foundation of early Northwest European culture. In this post, we’ll try to tell the complex coastal history of Late Antiquity. It’s a story that’s almost never told.

And, of course, after reading this post, you understand too why in the psyche of the West names of freebooters and mateys like Blackbeard, Dolhain, Jack Sparrow, Jacob Benckes, Captain Hook, Mansvelt, Klaus Störtebeker, Michiel de Ruyter, der schwarze Rolf, Rock Braziliano (also Brasiliano), Francis Drake, the Flying Dutchman, Captain Kidd, Grutte Pier (see end of this post), Godeke Michels, Black Bart, Grace O’Malley, Davy Jones, Piet Hein, Egil Skallagrimson, Long John Silver, and, of course, Gannascus (in this post more) have a special place.

Before we begin; why is this story almost never being told? The explanation is trivial and quite embarrassing for the academic world: their obsession with Vikings. This disproportionate emphasis on Vikings has distorted our view of Europe’s maritime history. As a particular scholar describes it: “The Vikings, in fact, were only the last episode of a long line of barbarian pirates harassing Europe,” and another quote, “The Viking age marks an accentuation of something long present.” Admittedly, the Vikings did so with a big bang. To this very day, almost twenty-four-seven new academic books or articles about Vikings are being published.

And while we’re at it, despite there’s much discussion among scholars as to why the Scandinavians started looting the western world around 800, one of the triggers was the accumulated wealth of the Frisians. Frisian merchants had established themselves during the centuries before all along the southern North Sea coast, from Flanders to Denmark. But also at towns on the British Isles, along the river Rhine up to Trier, and at towns in southern Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea. Frisians and Scandinavians were culturally akin in language, belief, and traditions. A desire to viking was created by the wealth and the long-distance maritime connections of Frisia (De Maesschalck 2012).

Therefore, let us quickly go to where and when it all really started.

1 – Arrival of the Romans

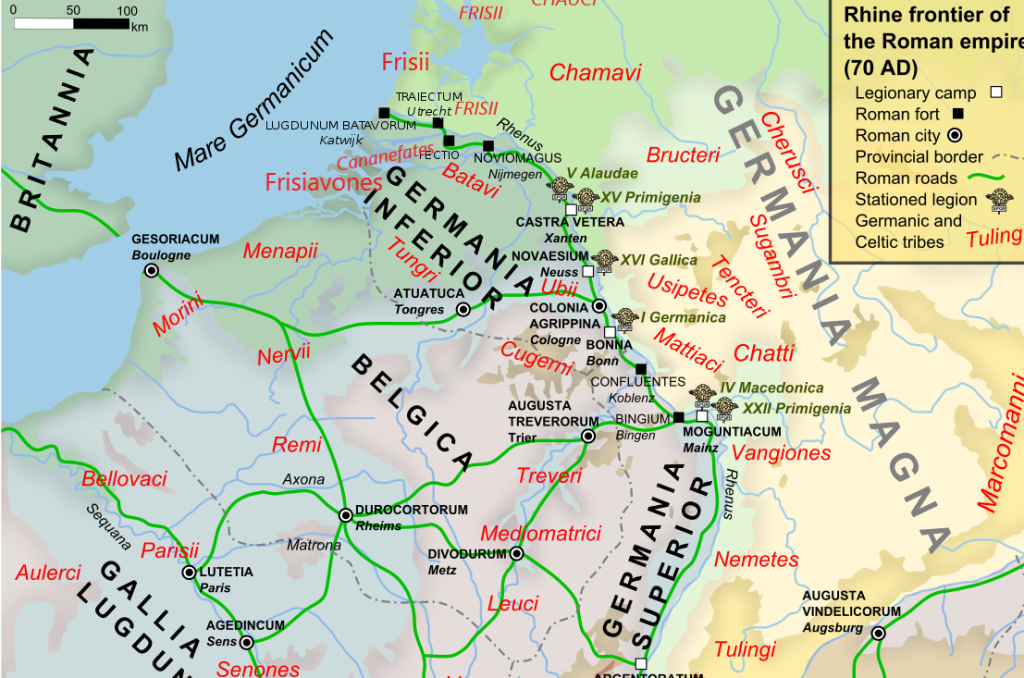

Led by none other than Caesar himself, the Romans conquered Gaul between 58-51 BC. It was around 15 BC that the Romans first set foot on the marshy soil of the largest delta in Europe, that of the rivers Rhine, Scheldt, and Meuse. The wetlands. There, where the ocean meets the sand, so to speak. If the Romans had made a proper business case beforehand, they probably would have saved themselves the trouble. It was General Claudius Drusus who arrived with an army in the central river lands of the Netherlands in 12 BC. According to the historian Tacitus, the Chauci were known for piracy, but were also one of the noblest Germanic tribes.

After a few decades of cumbersome and repeatedly disastrous military expeditions north of the river Rhine, including a maritime disaster during the military expedition under the command of General Germanicus Julius Caesar to subdue the Chauci in AD 16, during which an impressive Roman fleet of 1,000 small ships was wrecked by a storm and tide at the Wadden Sea near the mouth of the river Ems, and including a major defeat with no less than 1,300 casualties on the Roman side in the Baduhenna Woods against the Frisians in AD 28, the Romans settled with the lower river Rhine as the northernmost frontier of the empire on the Continent. Around AD 40, they started to erect the limes “border” of Lower Germanic Limes.

Barely were the first fortifications completed, when in the year 69 a large-scale revolt started that lasted two years, orchestrated by the Batavians, under the command of Gaius Julius Civilus. The Canninefates, under the command of King Brinno, the Chauci, and the Frisians also chipped in and were considered the bravest forces by Civilus. The naval power of these allied forces was mainly supplied by the Canninefates and the Frisians (Haywood 1999). Their fleet laid waste to the fort of Praetorium Agrippinae, currently Valkenburg, where two cohorts, about 1,000 soldiers, were deployed and captured a staggering twenty-four Roman galleys. These attacks of the Canninefates and the Frisians were the first act of war of the revolt of 69. It totally surprised the Romans, who were anticipating an attack from the Batavians instead (Van de Bunt 2020, Lugt 2021). The strikes of the Canninefates and the Frisians must have been a serious blow to the Roman classis ‘fleet’. At the North Sea, the fleet of the insurgents confronted a Roman convoy sailing from Britain. Maybe it was reinforcements because things were not exactly moving in the right direction for the Romans at the limes. The Batavians and Chauci ruined many other forts more inland.

A cohort of Frisians and Chauci operated high upstream the river Rhine, at the town of Tolbiacum, currently Zülpich in Germany, all the way near the present city of Bonn. These Chauci and Frisian rebels were defeated by the people of Tolbiacum. This success was achieved through a trick. The citizens of Tolbiacum had offered the Chauci and Frisians a banquet with a lot of wine. After the Chauci and Frisians had fallen asleep drunk, the doors were closed and the building was set on fire, all according to Tacitus’ Historiae.

Eventually, the Romans restored order in the central river area of the Netherlands. Under the rule of Emperor Hadrianus in the second century, the limes was heavily fortified.

However, at the end of the second century, things turned bad again, and Germanic tribes started to revolt and invade the Roman territory. At the same time, in the second century, a massive process of re-wetting of the landscape commenced. A process known as the Great Watering. Forts literally started to sink slowly into increasingly wetter grounds. Most forts in the west were abandoned during the already vertigo years of the third century. From around the second quarter of the third century, the economy shrank. Building activity south of the river Rhine tempered, fewer settlements, and gold money was hoarded (Buijtendorp 2021). Although the Romans restored order for a last time at the end of the third century, they soon afterward retreated south. The Roman road that connected Cologne via Maastricht and Tongeren with Bavia, on towards Boulogne-sur-Mer, also called the Limes Belgicus, became the new northernmost border of the empire. A border still traceable because it is more or less the dividing line between the French and the Dutch languages.

2 – Endemic piracy

And there where the Ocean streams, there live the Saxons, quick, hardened and skilled with weapons, and the Scridifinns [also Skridfinns meaning striding Finns, i.e. the Sámi] and the Frisians – and they are all feared as pirates.

Versus de Asia, between 635-637

The drivers behind the large-scale piracy (the word ‘pirate’ is derived from the Greek word peiratēs, meaning something like ‘to attack’) from the region north of the river Rhine along the southern coast of the North Sea were the following.

The new wealth the Romans brought to the region might have been a logical first reason. Think of all the wealth and food transported along the river Rhine and the transports between the Continent and Britannia. Indeed, greed. Maybe a trigger already soon after the Romans had arrived in the wet delta.

Secondly, climate change probably was a driver too. The traditional explanation is that because of a new period of marine transgression which started in the third century, known as the Dunkirk II period, the sea level rose and living conditions worsened along the low-lying coast. However, more recent insights suggest that a process of dune formation, sedimentation, and silting-up of tidal gullies in the wider North Sea basin led to the exhaustion of sedimentation sources in the North Sea. This, in turn, triggered an erosion process of the southern North Sea coast. The high-energetic sea attempted to rebalance its sedimentation level. Consequently, the closed dune-wall complex was breached, deep inlets were carved into the interior, and tons of peat were carried off to sea (Tys, 2002). Additionally, the aforementioned Great Watering was a defrosting process of the still frozen deep soil since the last Ice Age. It occurred due to the rise in temperature, causing the soil to shrink. Indeed, as we learned from boring physics class, water has a lesser volume than ice.

All these environmental processes gradually made much of the coastal land unsuitable for agriculture and living. The need to find additional resources became paramount. The already existing tradition of piracy received a boost.

Empty lands – Eventually, the population of the west coast of the Netherlands and of tidal marshlands in the north of Germany and of the Netherlands decreased. Especially in the fourth century populations were small. This must have coincided with regional migration movements.

Thirdly, perhaps stimulated by the Roman presence, shipbuilding and fighting techniques developed too. This enhanced the possibilities of piracy. Lastly, the fourth reason causing piracy to go to the next level in volume and complexity is that these Germanic tribes of the sub-Roman world started to operate in (large) confederations. The names Franks and Saxons are, in fact, primarily names to denote a confederation of tribes. Manum latronum exitialem ‘mischievous band of robbers’, as they were described by the fourth-century Roman soldier and historian Ammianus Marcellinus. We will come back to the Frankish and Saxon confederations further down.

The result was that piracy became an important means of livelihood for many tribes of the region north of the river Rhine.

The most well-known Germanic seafaring tribes of the first two centuries of the era are the Batavi, the Bructeri, the Canninefates, the Chauci, the Frisians, and the Usipi. Except for the Batavians and the Canninefates, who lived respectively in the central river land and between the mouths of the rivers Rhine (Rhenu) and Meuse (Helinium), the other tribes lived outside (mostly north of) the limes. The tribe of the Frisiavones may be considered as the Romanized Frisians (IJssennagger 2017). The part -avo means ‘belonging to/descending from’, so the people belonging to/descending from the Frisians (Neumann 2008). Archaeological research suggests that the Frisiavones populated the area between the river Rhine and the river Meuse from the mid-first century, similar to the civitas Batavii. Ceramics found of the Frisiavones are of Frisian (Frisii) tradition.

The Ampsivarii, a tribe that lived at the mouth of the river Ems, were pushed out by the Chauci soon after the Romans had arrived in the region and were never heard of again. Outside Roman control, these tribes could prepare their raids deep into Roman territory south of the river Rhine, on both coasts of the English Channel, and along the coast of Brittany. The coasts of their homeland were treacherous, providing protection against Roman punitive expeditions. The coast was (and is) shallow with strong tides and infested with gullies, inlets, islands, bays, sandbanks, and a total lack of points of reference, making navigation difficult in bad weather. Roman fleets were defeated by these elements (or lack thereof). Additionally, approaching this coast from the interior was extremely difficult due to the peatlands, swamps, lakes, and rivers that bordered it.

Of the Germanic tribes, the Chauci were the most notorious. We know that the Chauci and the Frisians were not only neighboring tribes but also that they shared the same salt-marsh culture of living on raised settlement mounds (i.e. a terp or Warft) above the likely flood line. An inhospitable, unprotected coastal zone of massive marshlands, frequently flooded, stretching from the current province Friesland in the Netherlands to the river Ems in Germany. The Chauci may also have settled on islands in the estuary of the river Rhine. Check out our post The shipwrecked people of the salt marshes to know how the Romans appreciated these tribes, and to understand fully what these terps (also wierde, Wurt, or Warf) were. A quite unique salt-marsh culture.

Thanks to the Roman historian and politician Tacitus (ca. 56-120), we know that the Germanic tribes were skilled seafarers. It concerns notes of a naval battle near the mouth of the river Ems in 12 BC, a battle between the Romans and the Bructeri tribe. The Bructeri were a tribe living further upstream the river Ems. Another account, also by Tacitus, recounts the phenomenal journey of the Usipi tribe. The Usipi lived further inland between Cologne on the river Rhine and the river Lippe. During a military campaign in Britannia in the year 82, a cohort of Usipi mercenaries mutinied from the Imperial Army. First, they commandeered three galleys. With these ships, which were not easy to master, they sailed north and circumnavigated Britannia. Then the Usipi mercenaries crossed the North Sea and sailed upstream the river Rhine, trying to make it home, apparently. Only on the river did they have trouble navigating. Here, the Frisians, who showed no mercy, either killed or enslaved the Usipi to be sold (Abulafia 2019).

Mercenaries – It was common practice for Germanic warriors of free tribes, outside the Roman Empire, to join the ranks of the Roman Army as mercenary, as this example of Ursipi warriors illustrates. Auxiliary troops of Frisians too, operated in Britannia, especially at Hadrian’s Wall in the second century. Read also our aforementioned post Frisian mercenaries in the Roman Army. This also shows that besides piracy, signing up for the military was another possibility for free Germanic tribes to get a slice of the (Roman) cake.

The Chauci entered history with raids against the province Gallia Belgica in the first half of the first century. The first record of a raid by the Chauci is in AD 41. Six years later, the Chauci appear in the annals again. This time we even have the name of their commander: Gannascus. Gannascus, who himself was a member of the Canninefates tribe, was captured by the Romans in the year 47. The years 47 and 48 were a period when the Chauci and the Frisians systematically raided the supply routes of the Romans, starting after the death of Sanquinius Maximus, the Governor of Germania Inferior (Van de Bunt 2020). The whole revolt was not taken lightly by the Romans because Emperor Claudius ‘sent in the cavalry’, so to speak. A military force led by none other than the successful General Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo. We can assume Gannascus was sent by Corbulo to Davy Jones’ Locker. The last time we hear of the Chauci is during the period 170-175, when raids were at their height. The Chauci were even carrying out operations in the Bay of Biscay. Simply because the Chauci were not mentioned anymore after 175, it does not mean they had given up raiding altogether and had become good and friendly people. The Romans merely gave a new name to these sea gypsies, namely Saxons and Franks, of which the Chauci, like other northern seafaring tribes, surely were a part (Van de Bunt 2020).

The last quarter of the second century, a pandemic hit Europe. Although still unclear what disease it was, estimations are that between fifteen to twenty-five percent died of it. The Roman army was hit notably hard. Not only did its soldiers die, but it was also more difficult to replace them. This made the limes more vulnerable to attacks by the Chauci. The pandemic might also be an explanation as to why relatively many hoards have been found since their owners had died (Buijtendorp 2021). Of course, the infectious and deadly disease will have affected the numbers of Chauci warriors, just like it did with the Romans.

3 – Litus Saxonicum

By around the year 200, the intensity of piracy was so widespread that the shores of northern Gaul from Brittany to Flanders, and of southern and eastern Britannia, were no longer safe to live in. The forebear of the adventus Saxonum ‘the coming of the Saxons’, i.e. the migration of the Anglo-Saxons to come within a few centuries. At the end of the first century, the Romans started to build fortifications at river mouths. These were the precursor of the Litus Saxonicum ‘Saxon Shore frontier’. Probably, fortifications also existed at the mouths of the river Scheldt and the river Rhine in the Netherlands. Due to marine erosion, these have been destroyed.

From around mid-third century, pirate activity increased yet again. The Frankish confederation started to roam the seashores for booty around 230. This big confederation consisted of the Ampsivarii, Bructeri, Chamavi, Chattuarii (i.e. the Hetware, known from the epic poem Beowulf), Bructeri, Ampsivarii, and Salians (Claes & Nieveler 2017). Possibly also the Canninefates, Chauci, Frisians and the Herules. Franks was the name they gave themselves, meaning possibly something like ‘fierce/bold’, or maybe ‘free’. The name Saxons or Saxones appeared for the first time in contemporary sources in the year 356 (Dhaeze 2019). Mistakenly the year 150 is often regarded as the first mention of the Saxons, i.e. the source of Ptolemy’s Geographica. However, the Geographica mentions the Abionec people which Tacitus recorded as the Aviones. This was subsequently copied into Greek as AΞONEC, translated as Axones and later ‘improved’ to Saxones, because that name was well known by then (Lanting & Van der Plicht 2020). Indeed, a whisper game, not played by children but by historians. Probably Saxon is the name of a confederation of the Reudingi and, thus, the Aviones tribes north of the river Elbe, Germany. However, where to pinpoint the Reudingi and the Aviones exactly is not very clear. The Saxons started to raid a bit later than the Franks, around 280. More theories exist about the term saxon. If interested in these check our post Have a Frisians cocktail, and discover as an aside the modern Frisians are, in fact, Saxons.

In the period 253-276, the Franks even looted in the heart of the ancient world. In the year 260, Frankish cursari ‘pirates’ sacked the cities of Tarragona and Tours, and the coast of North Africa. In 278, they suffered a defeat in the Mediterranean and were captured. For some reason, the Romans resettled them in Pontus at the Black Sea. A year later, the cunning pirates commandeered a fleet of the Romans and sailed from the Black Sea via the Bosphorus Strait into the Aegean Sea. They pillaged the coasts of Asia Minor, the Levant, and Greece. From Greece, they steered the fleet to the island of Sicily and sacked the city of Syracuse. From there, they even tried to raid the great city of Carthage in current Tunisia. Perhaps these pirates were inspired by the words of the late senator Cato: “Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam” (‘Furthermore, I consider that Carthage must be destroyed’). Here, for the first time, they suffered a defeat. Nevertheless, they were able to continue their sea voyage via the Strait of Gibraltar back to the river Rhine. The whole endeavour was described by the historian Zosimus in his Historia Nova, written at the start of the sixth century. We estimate such a boat trip must have taken about half a year, at least.

The Romans responded to the increasing pirate activity to further secure the coasts with fortifications and with more naval power. This is the legendary Litus Saxonicum ‘Saxon Shore frontier’ as described in the Notitia Dignitatum ‘List of Offices’ dated at the beginning of the fifth century. It is a series of forts and military fleets deployed along the southern and eastern shores of Britannia, and along the northern coast of Gaul. The Litus was built between 240 and 280. Check this map we made of coastal defences to have an overview of these fortifications.

There is some dispute among historians on how to precisely appreciate the Litus Saxonicum. Was it really an integrated defence wall, or more a series of separated structures? More probably it was the latter. Primarily to protect strategic points located along the coasts, mostly regional trading hubs often at river mouths. With a local military, stone structure, commodities could be protected, and the transport of troops and goods over sea be secured. In other words, bridgeheads for safe landings of ships. Think of the shipment of ore, grains, coal, livestock, and military supply. At the same time, these forts also facilitated the clearance and taxation of goods by the Roman authorities since these were regional commercial hubs too.

Be all that as it may, the period the Litus Saxonicum was built, coincides when piracy was a scourge in the area. Villas burned down all the way in Brittany, forts destroyed in Britannia, the reduction in the number of vici ‘trading settlements’ and the hoards found along the coasts of Brittany and Britannia that might indicate insecure times too (Abulafia 2019). So, no mistake as to why the Romans went through all the trouble and expenses. In 285, Roman commander Carausius was tasked to end the intense Frankish and Saxon piracy once and for all and to keep the seaways clear. He was successful but immediately accused by Rome of being in league with the pirates and kept some of the prizes of the pirates to himself. Also, punitive expeditions of the Roman Army into the river Rhine area were part of the strategy to suppress piracy (Pearson 2005).

Resisting temptation – The assignment of Carausius is documented in the Historiae adversum paganos ‘History against the pagans’ written by Paulus Orosius in the beginning of the fifth century. We cannot exclude Rome was right and Carausius could not withstand the pressure of the pirates and/or the appeal of their profits. In our post Sailors escaped from Cyclops we saw before how clergy were in league with pirates too, operating from the coast near Bremen in Frisia in the eleventh century. The former territory of the Chauci, by the way.

The ‘success’ of the Litus Saxonicum and the actions of Carausius were not long-lasting. In 280, the Frankish and Saxon confederations even started to combine their forces. The pirates were also simply called Germanic tribes by the Romans. Together, the confederations plundered the coasts of Belgica and Amorica, i.e. the coasts of Brittany and Normandy. Another raid is documented seven years later, namely that of the Herul tribe from Scandinavia, who plundered the river Rhine area. The origins of the Herul are a bit hazy, but possibly somewhere in Denmark or southern Sweden. Interesting to know, around the year 500, two Frisian raiders by the names Corsuld and Coarchion briefly established a kingdom in the region of Brittany. Check out our post A Frisian lord who ruled in Brittany, until his wife cheated on him.

In this period, Frisians were also active as pirates and in combat operations, even as far as in Belgica Secunda, modern East Flanders. This is supported by typical Frisian hand-made ware vessels discovered in modern Zele-Kamershoek, Belgium, dating around the year 300. Furthermore, from the Panegyrici Latini, i.e. the collection of twelve public speeches in praise of Roman emperors, we know that Emperor Constantius I resettled or deported Frisian and Chamavi raiders into the interior of Gaul. These Chamavi and Frisians had populated the central river area of what is now the Netherlands around the year 260, after the Batavi tribe had lost its special status in the year 212. However, the Frisians and Chamavi who had settled in the river area clashed with Emperor Constantius I in the Scheldt region in the year 293. Although the Roman records talk about Franci, they were, in fact, Frisians and other northern Germanic tribes. The Frisians lost, were made slaves, and were deported to Belgium and northern France (Lanting & Van der Plicht 2010, Dhaeze 2019). Also, the Panegyrici Latini describe the Frisians as praedatores ‘looters’ (Haywood 1999, Dhaeze 2019).

The first decades of the fourth century, the Frankish pirates started raiding the coast of Spain, and as far north as Orkney. Halfway through the fourth century, Frankish incursions into the Roman territory in the river Rhine area took place. A Roman fleet of six-hundred ships had to restore Roman hegemony, albeit briefly, in the river area again. Not long after, however, things went totally wrong for the Romans. The Celtic and Germanic tribes teamed up.

4 – Barbarica conspiratio and the pull-out of the Romans

As described, the Romans had retreated from their limes along the lower river Rhine over the course of the third century, although they maintained their influence over the lucrative central river area until circa 460 when the region came under Frankish rule (Looijenga 2023). Around the year 320, Emperor Constantine made a treaty with the Franks to help defend the limes in the Rhine area. Between 396 and 402, Commander Stilicho inspected the limes and again treaties were made with the Franks (Dhaeze 2019). Of course, all this came with a heavy price for the Romans to pay to the Franks. Influence was achieved with money, by buying alliances. The gold hoard of Lienden, dated around 465 and found in the central river land in the Netherlands, just east of Wijk bij Duurstede, might be an example of these politics. Similar deals were probably made with tribes north of Hadrian’s Wall in Britannia, but also with the Frisians, of which the hoard found in Winsum is an example (Dhaeze 2019). A strategy identical to how CIA agents went with suitcases filled with money into the mountains of Afghanistan to buy alliances of local warlords and their tribes during the ’80s of the last century (Coll 2005). Who knows, maybe our modern superpowers still do.

Halfway through the fourth century, the situation in Britannia started to become untenable, despite the Litus Saxonicum. In 367, not only raids of Frankish and Saxon pirates were launched onto the shores of Britannia, but also from the north, the Celtic tribes – the Attacotti, Picts, and the Scots – revolted and broke through the borders. It is the year the Romans called the barbarica conspiratio ‘barbarian conspiracy’. Perhaps they were right, and the pressure on Roman forces was coordinated among the barbarians on both sides of the North Sea indeed.

“Enough is enough,” the Romans must have thought, and in the year 410 Rome pulled out of Britannia as well. Leaving the defences to the Romano-Briton civitates ‘citizens’ themselves. Following the barbarica conspiratio, piracy remained endemic, roughly until early-sixth century. There was one twist in the story, however.

After the collapse of Roman power in Britain, Germanic tribes started to settle. Indeed, the adventus Saxonum ‘coming of the Saxons’ had started, as described in Gildas’ De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae ‘On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain’ written around 540. The first evidence we have that Germanic tribes settled in Britannia is in the year 429. The Chronica Gallica ‘Gallic Chronicle’ of 542 testifies to Saxons getting a foot in the door at the Isles and gaining control over a significant part of England. Germanic tribes were making their way into Britain, most of them from northern Germany, Frisia, and southern Scandinavia (Fleming 2010). Settlers in search of land may have arrived in small boats, accompanied by their wives, children, and livestock. There were also foreign tribes with the purpose of political conquest, aiming to make life difficult for the native walhaz. Thus, the Anglo-Saxon history had commenced.

Wealhaz – The West Germanic term walhaz means ‘foreigner’, or more specifically ‘a person of Celtic or Romance speech’. In other words, walhaz is the perspective of a Germanic-speaking neighbour of the Roman Empire, living in what is now Flanders, Germany and the Netherlands (Schrijver 2014). On the Continent the term walhaz survived as ‘wahl’ in German (e.g. Walchensee) and ‘waal’ in Dutch (e.g. Waalwijk and Walonia) to denote people who spoke Romance. A walnut is therefore: a nut from France, where the people speak Romance. In Old English walhaz developed into ‘wealh’ or ‘wealhas’ and retained the inherited meaning of ‘foreigner’ to indicate (interestingly) the indigenous people of Britain, being of lower status. In the West Saxon dialect of Old English ‘wealh’ was even a synonym of slave.

The raid around 525 of Danu rex Chlochilaichus, probably Hygelac of the epic poem Beowulf, into Frisia at the river Rhine, was the last pirate activity recorded in written sources. Read also our post Ornament of the Gods found in a mound of clay about this disastrous expedition. This expedition is the end of centuries of the so-called Saxon migration and piracy, where, in fact, Saxons included Jutes, Angles, Frisians, and even Franks (Lebecq 2005).

5 – Ships and modus operandi

One of the most important things you need as pirate is a sword and a ship. We put the sword, cutlass, seax and other weaponry stuff aside and shall focus on ships.

Ships

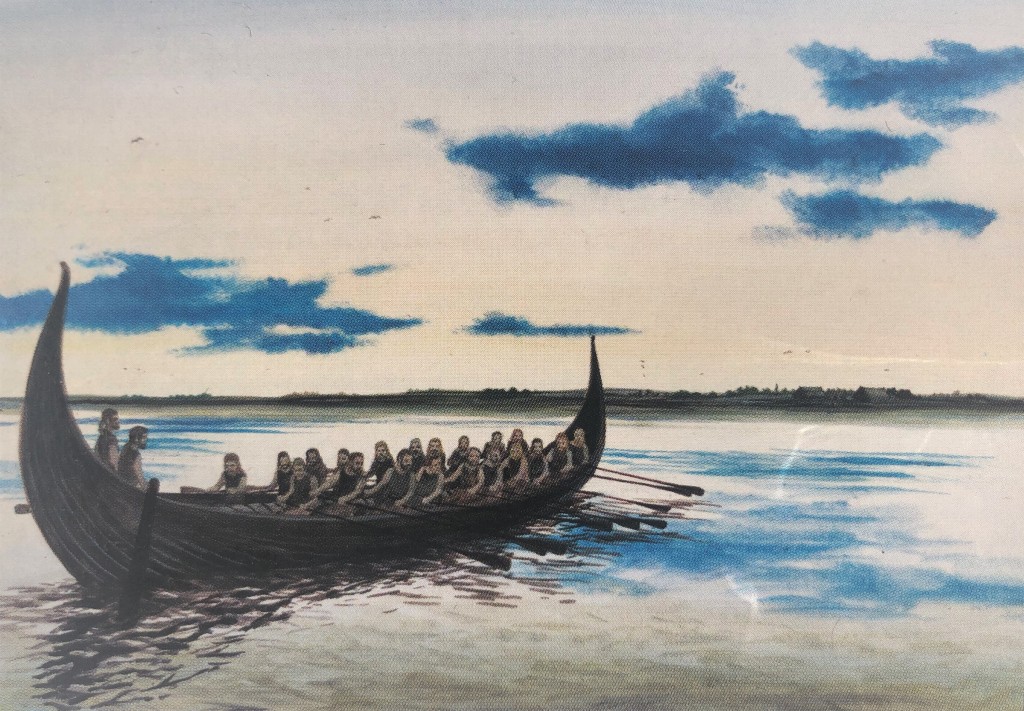

In the words of Tacitus, the pirates used a ‘medley of ships’, some propelled with oars, some with colorful cloaks used as sails. According to Pliny’s “Naturalis Historia,” their boats were hollowed-out trees that could carry up to thirty warriors. Pliny’s description might suggest the fleet was inferior, but it was not. Actually, the fleet was quite professional (Pearson 2005). It is a misconception that the Germanic tribes did not use sails. The quote of Tacitus, in fact, already makes it clear that they did. Furthermore, from the neighbouring Celts, we know they used sails for sure, and of course, there were contacts between the Celtic and Germanic tribes. The thing was, however, that the Germanic tribes made less use of the sail at first. The explanation for this was that there simply was not much need for it. Warships were traditionally propelled by paddles and later by oars. Above all, a warship had to be manoeuvrable and not dependent on a favourable wind to attack or retreat. And since the crew of a warship had to be as big as possible anyway, a sail was not needed. For commercial transport, however, the opposite argument was the case. A small crew is more economical, and thus the use of sails is reasonable. However, when piracy over longer distances became an increasingly practiced, the combination of ships propelled by oars and by wind came more into use.

In the centuries before the era until the first century, boats of the so-called Hjortspring-type were widespread in southern Scandinavia. These were boats of about seventeen meters long and had space for about twenty men paddling. These boats were built in the Nordic clinker-built tradition, thus where the edges of the hull planks overlap each other. By the end of the first century, the Hjortspring-type had been replaced by more sophisticated, also clinker-built, ships with oars. Much like the ships found in Halsnøy, Norway, and in Björke, Sweden.

In the rhine River area, around the beginning of the era, flat-bottomed ships and barges were built with sails. Several barges have been found in Zwammerdam, the Netherlands. These were used for commercial transport. The construction technique was flush or carvel-built. With this technique, the edges of the hull planks are placed close together.

In Bruges, Belgium, a cargo ship was found, dated around 200 AD. It was a flat-bottomed vessel, approximately fourteen meters long, and equipped with a sail. Similar to the Rhine barges mentioned earlier, this ship was also carvel-built. Another ship, known as the Blackfriars I shipwreck, was excavated in London, UK. This ship, dating back to the second century, also had a sail. Both the Bruges and Blackfriars I boats are considered ancestral to the cog ship, also known as kugg or kogg(e). The cog ship, with its significant carrying capacity, became the dominant ship type of the Early Middle Ages and was believed to be the typical vessel used by Frisian merchants. It is even thought to have been developed by the Frisians themselves (Westerdahl 1992).

In Nydam Moss in Denmark, three ships were found. The best conserved is the Nydam Oak ship. The findings illustrate that by 300 the Germanic tribes already possessed quite seaworthy boats and warships. The Nydam Oak ship is a twenty-one meters long Man-O-War, and had space for thirty rowers annex warriors. Maybe it could carry a crew of in total of forty (probably) men. The ship was built in the Nordic tradition, namely clinker-built. The number of warriors nicely fits the description of Pliny, see above.

Modus Operandi

Besides ships, we have seen from where the pirates operated, the current Wadden Sea coast of Germany and the Netherlands, which are now the regions Friesland, Groningen, Ostfriesland, Butjadingen, Land Wursten, and Dithmarschen. An area that was outside the sphere of influence of Rome, and its waters were, as described earlier, treacherous and hard to navigate. The only chance to have success with a military operation in this ever-changing tidal landscape was to engage locals in the army. Otherwise, you were doomed to get stuck in the mud or get stranded on a tidal plate or sandbank. It was an impenetrable water land. After the Roman Empire retreated south and abandoned the limes at the lower river Rhine, Germanic tribes made use of this, and the central river area, including the mouth of the rivers Rhine, Meuse, and Scheldt, became excellent safe havens as well for pirate operations. These are the current regions Flanders, Zeeland, and Holland.

In their wetlands, pirate operations were planned, prepared, and carried out by the freebooters (a word, by the way, originating from the Dutch word vrijbuiter ‘free booter’). These pirates possibly went out to sea for plundering during the sailing season from spring to autumn. The borders of the Roman Empire in the region were difficult to protect as well, due to the English Channel separating Gaul from Britannia. It served as an excellent gateway directly into Roman territory. The Roman supply chain via sea between the island and the Continent was vulnerable and hard to protect. Initially, the distances the pirates covered were fairly limited and did not extend beyond the eastern and southern coast of Britannia and the northern coast of Gaul. It took the raiders eight to nine days of rowing to travel from the Wadden Sea to Gaul. To reach Kent, it took them about ten days (Dhaeze 2019). However, over the course of the third century, pirates operated in the Bay of Biscay and in the Mediterranean as well. Rest periods were essential during their nautical operations on the coast of Britain, so it is likely that the pirates rested in coves and inlets before launching their attacks (Pearson 2005).

The exact places from where Frisian (and Chauci) raiders operated is difficult to say. But based on a recent inventory of Roman period swords (mostly parts like pommels, cross-guards, and grips) found in the provinces of Friesland and Groningen (Spiekhout et al 2023), their hiding places in their homelands are uncloaked. We have plotted the rough provenances on a map; see below.

A however, not much debated when talking about these early pirates is so obvious that it is overlooked, namely: what counted as booty? Easily it is assume that it was gold, silver, armor, fancy bronze statues stuff, etc. Important goods for having prestige in a client system. But was this available in large quantities making a raid economical? How much gold and silver was there to rob along the coastal settlements anyway? There was a limited money economy. Or was all about obtaining women and slaves, as it would be in the Early Middle Ages and in the Early Modern Period? And, whatever it was, randomly rowing into the Strait of Dover, steering your ships ashore at the first sight of a smoking fireplace in a village, is unthinkable. Is too simple. What was it they were after, and how did they know where to find it? And, how was it possible to surprise settlements along the coast? Check our post The Raider’s Portrait of Appels to get a feel of how they did their planning and plundering.

Or were they indeed scanning the coasts just as long until they found a weak area. In 455-457, the Herules tried their luck in Galicia, but were not successful. After that, they moved east and raided the Basque Country and Gascony. After this, in 458-462, they returned to Galicia but went on to Andalusia. This way, they got familiar with these areas (Dhaeze 2019). To us, this feels too much like a serendipitous approach still.

Another aspect is that the theories suggest piracy increased due to climate change, causing much arable land along the low-lying coasts to be lost. In other words, raiding as a means of compensation. Consequently, this must mean that with the looted treasure, food and goods were purchased somewhere else in the region. But where and how? Where were still surpluses of food available, and where were those markets? Or were, for example, livestock and grain part of the booty too? If the answer is yes, what were the implications for (the size of) their fleet, type of ships, and their operations in general, to transport this type of booty? Read also our remarks on this aspect concerning the yearly raids of the Vikings on Dorestat in the ninth century, in our post The Batwing Doors of Northwest Europe.

We welcome any suggestions on this matter of the booty.

Related to the former question is, how do these pirates choose their targets? We may assume the potential loot was protected by the Romans and Britons. We also know that these pirates were capable of attacking and laying waste to fortresses and villages. If we take the Nydam Oak ship as a reference, you had about forty warriors per ship. That barely seems enough to challenge a fortified village with military presence. The ninth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle often speaks of parties of three ships forming a raiding party or making a landing. That would be a hundred and twenty warriors at most. We would be interested in studies that have estimated the size of a village along the south or eastern coast of England, the number of legionaries deployed at the fortress, and consequently how many pirates it would take to launch a successful attack.

Anyhow, a fleet of ships, shipbuilding, careful targeting, up-to-date knowledge of the seaways and the ‘Saxon Shore’ itself, and thorough planning were all absolute preconditions. Combining this with the fact that the homelands of these pirates consisted of only quite small settlements, these operations must have covered an extensive area. Making the operations of the warrior bands probably polyethnic, necessarily beyond primary tribal entities (Dhaeze 2019). Explaining also the formation of confederacies. Many settlements must have been involved already for a single raiding operation. And probably different raids took place each season simultaneously; otherwise, these would not have been a real threat and headache for the Romans, as we have seen earlier in this post. It also must have taken months of careful preparations, possibly during wintertime.

6 – The new, buccaneer culture

The reader might compare all the different episodes and raids mentioned above to a pinball machine that releases ten balls at the same time. The beginning of the common era was a dynamic period. The summary, however, is that it was a time of the “growing importance of power configurations with the emergence of politicized ethnic and sub-ethnic communities” (Fernández-Götz & Roymans 2015). Simultaneously, the Germanic tribes living along the southern coast of the North Sea engaged step by step in full-fledged piracy. The Chauci, Frisians, Herules, and Chaibones are the sea raiders of the first hour, of which the Chauci stood out (Dhaeze 2019). Covering ever greater distances and forming growing coalitions or confederations. At first, these confederations were mainly known as Chauci, then as Franks (of which the Frisians were probably part too), and shortly after also as Saxons. Or, just as ‘Germanic pirates’. Piracy had become an essential part of the survival strategy of these sea-tribe societies.

It is also true that during this period the cult of the god Wodan developed. His cult developed relatively late, around the beginning of the era. Therefore, coinciding with increased raiding activity. Wodan is the god of warriors, and his cult might reflect the changes in society, from mainly agricultural towards (also) a warrior culture.

Wolf-people and land of hills

The confederation of the Franks needs an additional commentary. Generally, we tend to think of them as a landlocked tribe, but their origin was, in fact, a maritime one. Already the name Merovech, leader of the Salian Franks, who lived in the mid-fifth century, reveals their watery origin. Mero means ‘sea’, and wech or vech stems from wioh or weoh, meaning ‘holy’ place. Hence ‘sea shrine’ (Shippey 2022). The Romans also considered the Franks a seafaring people. The cradle of the Franks is the southern coast of the North Sea. In early sources, the Franks are identified with the Húgas or Hugones, or with King Huga of the Franks. These texts are the eighth-century poem Elene, the tenth-century epic poem Beowulf, the also tenth-century Res gestae Saxonicae, and the eleventh-century annals of the Abbey of Quedlinburg. The northern region in the Netherlands bordering the Wadden Sea in the current region of Humsterland in Groningen was called Hugumarchi ‘Mark of the Húgas’ in the Early Middle Ages. Other name variations were Humarcha, Hugmerchi, and Hugmerki. Although the Húgas tribe left this region towards more inland and were replaced by the Frisians or Chauci, the name Humsterland has survived (Van der Tuuk 2016).

Another theory (Van Renswoude 2022) concerning the Húgas and Hugumarchi, is that both names have, in fact, nothing in common. The word húga(s) derives from a verb still being used in the northeast of the Netherlands, namely hoegen or hugen. But also traceable in the Dutch personal names Huig, Huygens and Huibert. The verb hoegen or hugen means something like to long, to yearn, or to lurk. And huga is a poetic metaphor for a wolf. So, the wolves or wolf-people. If interested in the importance of the wolf in the North Sea region already for ages, read our post Who’s afraid of Voracious Woolf? The king names Huga and Thiadric that are associated with Franks, are typical for coastal speeches, including Frisian, This supports that the Húgas came from northern Netherlands. An explanation would be that the Húgas were a sub-tribe of the Frisians migrating south and merged with other tribes into the Frankish confederation (Van Renswoude 2022). This corresponds with all the migration movements described in this post during the first half of the first millennium.

The name of the area Hugumarchi might not be ‘Mark of the Húgas’ at all. Instead, hugu derives from Old Germanic huguz, which is related to Eastphalian höge, classic German Hügel, or Old Norwegian Hugl, meaning high or hill. In other words, the artificial mounds known today as terp, wierde, Warf etc. of this region. The element mark had the meaning of ‘common land’ in the north of the Netherlands. So, Hugumarchi, today’s Humsterland, might be understood as ‘common land of terps’ (Van Renswoude 2022).

Anyway, apart from the exact explanation of the word Húgas and Hugumarchi, the bigger and generally accepted picture is that around the beginning of the era, the Salians, or Salian Franks, part of the Frankish confederation, started to move further south during the second half of the third century. Facilitated by crumbling Roman power, the long-haired Salians settled at the mouths of the rivers Rhine and Scheldt. From there, they engaged in piracy at the close of the third century. Subsequently, the Franks occupied Toxandria, more or less the current Brabant regions in Belgium and the Netherlands. Later, the power and jurisdiction of the Franks expanded further. The capture of the town of Cambrai, also known as Kamerijk, in northern France by their leader Chlodio in the year 430 marks the beginning of Frankish rule, and of Francia.

We understand all this information concerning the Germanic origin of France is devastating for any proud Francophile.

The result of all these movements, changing alliances, and joint enterprises during a period of around five centuries was a relatively cultural and linguistic homogeneity, also called Nordseegermanisch ‘North Sea-German’ (Lebecq 2005). A big melting pot. Communities that were very connected via waterways and seafaring skills. That was quite a different situation before it all started. At that time, the Germanic tribes of the sub-Roman world were not entities held together by (again a long German term) a Zusammengehörigkeitgefühl ‘belonging-togetherness’, but were tribal diverse in origin. What brought them together, step by step, was probably the search for loot (John 1996).

coastal Dutch language

The common language they developed during the Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages is described as a ‘Saxon’ pirate-settlers language, and called Coastal Dutch in linguistic research. It is an early form of Frisian and was spoken from the coast of Flanders to the northwest of Germany. It is generally agreed that the similarities between Coastal Dutch and English date from this period (Schrijver 2014). When piracy in the British Isles gradually was replaced by settlement in the fifth century, this common language (and culture) was exported to England, explaining the similarities between English and Frisian to this day. Some even speak of ‘heavy migration’ from the Low Countries to Britain, both preceding and following the Anglo-Saxon migration, being the basis for the common language (Chamson 2014).

The offspring of this language on the Continent only survives in province Friesland in the Netherlands, and in enclaves further east in northwest Germany, i.e. Saterfrisian and Nordfriesisch. Today, around 350,000 people speak it as a mother tongue, and these numbers are steadily declining.

7 – Rebirth of trade

The pull-out of the Romans, the common North Sea culture that had developed during Late Antiquity, but also the improving climate conditions, were the foundations of the rebirth of commercial activities. In fact, the existence of such widespread linguistic communities facilitated contacts between the different shores of north-western Europe. Toward 600, the Frisians and the Anglo-Saxons emerge as the chief instigators of this commercial rebirth. Also, read our post Porcupines bore U.S. bucks to learn more about the extensive volume of early-medieval Frisian free trade.

At the turn of the sixth and seventh centuries, the whole wider North Sea region seems to have been affected by this revival of commercial activity. The chief ports of the commercial web were: Quentovic, Walcheren, Dorestad, Lundenwic, Ipswich, Fordwich, Sandwich, Eoforwich, Hamwih, Ribe, and Sliaswich. A gazetteer of emporia (Lebecq 2005). If you want to know more about emporia Dorestad, current Wijk bij Duurstede in the Netherlands, and Ribe in Denmark, check out our posts The Batwing Doors of Northwest Europe and To the end where it all began: ribbon Ribe.

8 – Land of the Free

The role of the Frisians in this piece of history is not a very prominent one, as you might have already read. They were one of those Germanic seafaring tribes bordering the Roman Empire and undoubtedly participated in the many coalitions of pirate bands. During the period ca. 325-425, almost all of them had abandoned their lands when living conditions, climate-wise, deteriorated. It is very conceivable that the original Frisians had blended into the big confederations, especially those of the Franks and the Saxons.

Historians have wondered, and still do, how it is possible that despite the nearly total depopulation of the Frisian territory, the name Frisia survived, and even was adopted by the new settlers from further east and southern Scandinavia. It was from the Roman period that it became silent in the sources about the name Frisian, only to resurface in the seventh century in written sources. Some say that the new settlers conformed to the old name given to them by the Frankish elite, namely Frisians. Others say, “The people in the coastal areas who united themselves in order to stop the Franks, and got the name ‘Frisian’ pinned on them, but by whom is not clear. Apparently, the name was still floating above the area, as it were, and descended on the people who were living there and then” (Lugt 2021). With this post, we also made our point that these were not the reasons, and you certainly do not need to fall back on biblical parallels with a holy spirit descending with Pentecost.

The real reason is: because of what the name meant. It was a badge of honor. The word ‘frisia’ might have derived from the Old-Germanic word frīsijōz and frijaz. This meant something like ‘the free’ or ‘the unbound’ and ‘the brotherly’ (Van Renswoude 2012). No name could be more fitting for the new colonists repopulating the tidal marshlands again in the second quarter of the fifth century: the land of the free. It was, after all, still in a time when pirating was still a vivid part of the region. It was a name that may have been remembered within the entire North Sea socio-economic network, and the new Frisians naturally called themselves Frisians (Nieuwhof 2021).

Avast! Frisia, the free land of freebooters, where the ocean meets the sand.

We can live together

wolfmother

Where the ocean meets the sand

Won’t you take me to the

To the Gypsy Caravan

Epilogue

Despite that the heyday of piracy at the southern coast of the North Seas was over at the start of the sixth century, it remained a weak spot for the region. From Adam of Bremen’s Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum ‘Deeds of bishops of Hamburg church,’ we know that Frisian capers operated from the mouth of the river Weser, the territory of the Chauci pirates in Roman times. Want to know more about these lying pirates? Check out our post Sailors escaped from Cyclops. By the way, the word ‘caper’ is maybe derived from the Old Frisian word kopia which means ‘to buy.’ That is also a way of putting it! And, it did not stop after the Middle Ages. Piracy, alias privateering, became an essential part of the rebellion and warfare of the Dutch Republic during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. It was piracy in the Wadden Sea archipelago that played a prominent role in all of this. Read our post Yet another wayward archipelago to learn more.

Klaus Störtebeker – After the Privateers’ War between the House of Mecklenburg and Denmark had ended at the closing of the fourteenth century, the pirates under the name Victualienbrüder ‘Victual Brothers,’ who had fought alongside the House of Mecklenburg, were kindly thanked for their efforts. Everybody knows that one of the most difficult things in life is telling a group of pitiless pirates to quit what they are doing, to stop making easy money. It took an army of battle-hardened Teutonic Knights to drive the Victualienbrüder from their stronghold, the island of Gotland, and kick them out of the Baltic Sea.

One of the most famous captains of the Victualienbrüder was Klaus Störtebeker, probably originating from the town of Wismar, although legends differ. After the disaster against the superior Teutonic Knights, Klaus Störtebeker fled with a fleet to the coast of Frisia, the current region Ostfriesland, which in Roman times was the territory of the Chauci. Here he was granted safe haven by the local chieftains (Lehr 2022). However, the Hanseatic League, led by the city of seven towers Lübeck, captured Störtebeker together with eighty-three of his men in the year 1400. In Hamburg, he was beheaded together with most of the men.

Störtebeker un Güdje Micheel, de beiden roovden like Deel to Water un nich to Lanne.

Bet dat et Gott in Himmel verdroot, do wurden se beid toschanne.

old hymn from Ostfriesland

A year later they captured another pirate captain, Güdje Micheel also Godeke Michels, when he was with his fleet in -again- Frisian waters, near the mouth of the river Weser (Meier 2004). Both Klaus and Godeke had to walk the plank. In the harbor of Hamburg you can find a statue of Klaus Störtebeker.

It was a bad decennium for pirates and privateers, because in 1407 the Chinese admiral Zheng He destroyed in the Straits of Malacca the marine pirate kingdom of the notorious pirate Chen Zuyi. Chen Zuyi and tow other leaders were captured, brought back to China, and executed (Lehr 2019).

Pier Gerlofs Donia – A final pirate who must be mentioned is Greate Pier. His actual name was Pier Gerlofs Donia, and his nickname was Kruis der Hollanders ‘Cross of the Dutchmen’. He originated from the village of Kimswerd in the province of Friesland. Legend has it that he was really tall and big and had a blunt speech and attitude (plomp van spraeck en wesen). His alleged sword of more than two meters is kept in the Fries Museum. After new research published in 2022, the sword might very well be his true sword. He received his nickname for terrorizing the Zuyderzee or Southern Sea in the period 1515-1520. Greate Pier, also known as Grutte Pier, is also known from his Biblical-inspired acid test to identify possible spies of his nemesis, the Count of Holland. This test is known as the shibboleth: “bûter brea en griene tsiis, wa’t dat net size kin, is gjin oprjochte Fries” (butter, bread, and green cheese; whoever cannot say that is not an upright Frisian). Today, the Frisians mostly refer to him euphemistically as a freedom fighter. This year (2020) marks the five-hundredth anniversary of his death, and he is being commemorated with a movie as a hero. Nevertheless, Grutte Pier has recently been indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Frisia (ICTF). Find here the press statement concerning his indictment and the ICTF and more background in our posts How great was Great Pier? and How great was Great Pier (the sequel).

The story of Greate Pier is often portrayed romantically. He was a farmer whose farmstead was ransacked and family murdered by a raiding army hired by the Dutch. In response, he takes action and builds his own naval fleet to fight the Hollanders. However, in reality, Pier was a wealthy landowner who descended through his mother’s family from a hovedling or haadling, which was a noble class in the province of Friesland during the Late Middle Ages. His father-in-law was named Sybren Bonga, who was also a hovedling (De Langen & Mol, 2022).

Interestingly, in the area of the village of Tannenhause, just north of the town Aurich in Ostfriesland, the saga ‘Butter, Brot und Käse‘ (butter, bread, and cheese) exists. It is the saga about a giant who was buried there, together with a lump of butter, a bread, and a piece of cheese for his journey to the world of spirits. Over time, the three gifts turned into stone. These can still be seen today.

The Great Pier’s sword seems long, but, of course, cannot match the Japanese Haja-no-Ontachi, meaning ‘great evil-crushing sword’. It was forged in the Edo period in the year 1859, with a length of 4.65 meters and weighing 75 kilograms. So, it is more than twice as long as the one of Great Pier.

Radio Veronica – Before we round up, another kind of piracy happened in the same waters. In 1959, the German lightship Borkum Riff III was sold to the Dutch pioneer Radio Veronica, to be converted into an offshore radio station at the docks of the harbor of Bremen. As the name makes clear, this lightship used to mark the reef near the Wadden Sea island Borkum, in the Ostfriesland region. Pirate station Veronica broadcasted from the North Sea from 1960 until 1974. Soon after Veronica began broadcasting, other radio-pirate ships started broadcasting too from the North Sea. This competition even led to a bomb attack by the Veronica crew on another pirate ship in 1971. We are not joking: DJs at war. Three years later, the Dutch government introduced an anti-piracy law to end all this anarchy and violence at sea once and for all. Why hadn’t the Romans thought about legislation too?

Note 1 – Above, we have suggested that the tribe’s name of the Frisians can be explained as ‘the free’ or ‘the unbound’. However, it is fairer to assume that the Romans gave the Frisians their tribe’s name in the first century. The name Frisii or Fresones derives from the Vulgar Latin verb fresare, meaning ‘to cut/to dig’, and referred to how Frisians cut a myriad of ditches into the soil. This was a way to drain and cultivate the wet, tidal landscape. For a more elaborate explanation, see our post A severe case of inattentional blindness: the Frisian tribe’s name.

Note 2 – In this post, we used the word cursari or cursarius, which is Latin for raider(s). Pirates of the Barbary ‘Berber’ Coast, i.e. the North African coast, were often called corsairs. Corsairs, just like privateers, were ‘authorized’ pirates. Privateer, by the way, is a contraction of private and volunteer. The distinction between authorized piracy and piracy proper was never clear-cut. The word ‘pirate’ is derived from the Greek word peiratēs, meaning something like ‘to attack’. Another synonym for pirates is freebooter, which stems from the Dutch word vrijbuiter, meaning something like vagabond. Lastly, buccaneer, again a synonym for pirate, originates from the French word boucanier. A boucan was a wooden frame to dry meat, so those who have a boucan mainly used it for pirates in the Caribbean.

Suggested music

- Wolfmother, Gypsy Caravan (2016)

- Radiohead, Man of War (2017)

- Inge van Calkar, The Ocean Never Ends (2020)

Further reading

- Abulafia, D., An ancient history of piracy. How advances in sea power and changes in climate led to widespread piracy at the edge of the Roman Empire (2019)

- Abulafia, D., The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans (2019)

- Buijtendorp, T., De gouden eeuw van de Romeinen in de Lage Landen (2021)

- Bunt, van de A., Wee de overwonnenen. Germanen, Kelten en Romeinen in de Lage Landen (2020)

- Chamson, E.R., Revisiting a millennium of migrations. Contextualizing Dutch/Low-German influence on English dialect lexis (2014)

- Claes, B. & Nieveler, E., The Frankish Kingdom. Hub of Western Europe (2017)

- Coleman, C.K., British Sea-Power in the Age of Arthur (2017)

- Coll, S., Ghost Wars. The secret history of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (2004)

- Cusack, C.M., Between Sea and Land: Geographical and Literary Marginality in the Conversion of Medieval Frisia (2021)

- De Maesschalck, E., De graven van Vlaanderen (861-1384) (2012)

- Dhaeze, W., The Roman North Sea and Channel Coastal Defence. Germanic Seaborne Raids and the Roman Repsonse (2019).

- Doedens, A. & Houter, J., De Watergeuzen. Een vergeten geschiedenis, 1568-1575 (2018)

- Ellmers, D., Frisian and Hanseatic merchants sailed the cog (1985)

- Engelkes, G.G., Der schwarze Rolf (1936)

- Fernández-Götz, M. & Roymans, N., The Politics of Identity: Late Iron Age Sanctuaries in the Rhineland (2015)

- Fleming, R., Britain after Rome. The Fall and Rise 400 to 1070 (2010)

- Fouracre, P (ed.)., The New Cambridge Medieval History. Volume I c.500-c.700; Hamerow, H., The earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms; Lebecq, S., The northern Seas (fifth to eighth centuries) (2005)

- Gelder, van J., Nieuwenhuis, M. & Peters, T. (transl.), Plinius. De Wereld. Naturalis historia (2018)

- Härke, H., Review of S. McGrail (ed.), Maritime Celts, Frisians and Saxons (CBA Research Report 71), London 1990, and John Haywood, Dark Age Naval Power: A re-assessment of Frankish and Anglo-Saxon seafaring activity (1991)

- Harrington, S. & Welch, M., The Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms of Southern Britain, AD 450-650. Beneath the Tribal Hidage (2014)

- Haywood, J., Dark Age Naval Power. A Reassessment of Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Seafaring Activity (1999)

- Heeringen, van R.M. & Velde, van der H.M. (eds.), Struinen door de duinen. Synthetiserend onderzoek naar de bewoningsgeschiedenis van het Hollands duingebied op basis van gegevens verzameld in het Malta-tijdperk (2017)

- Heijden, van der P., Romeinen langs de Rijn en Noordzee. De limes in Nederland (2020)

- Jacobs, T.J.M., Friese vorsten (2020)

- John, E., Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England (1996)

- Langen, de G. & Mol, J.A. Friese edelen, hun kapitaal en boerderijen in de vijftiende en zestiende eeuw. De casus Rienck Hemmema te Hitzum (2022)

- Lanting, J.N. & Plicht, van der J., De 14C-chronologie van de Nederlandse pre- en protohistorie VI: Romeinse tijd en Merovingische periode, deel A: historische bronnen en chronologische thema’s (2010)

- Lanting, J.N. & Plicht, van der J., De 14C-chronologie van de Nederlandse pre- en protohistorie VI: Romeinse tijd en Merovingische periode, deel B: aanvullingen, toelichtingen en C-dateringen (2012)

- Lehr, P., Pirates. A new history, from Vikings to Somali raiders (2019)

- Looijenga, T., Frisian Runes Revisited and an Update on the Bergakker Runic Item (2023)

- Looijenga, A., Popkema, A. & Slofstra, B., Een meelijwekkend volk. Vreemden over Friezen van de oudheid tot de kerstening (2017)

- Loveluck, C. & Tys, D., Coastal societies, exchange and identity along the Channel and southern North Sea shores of Europe, AD 600–1000 (2006)

- Lugt, F., Rijnland in de donkere eeuwen. Van de komst van de Kelten tot het ontstaan van het graafschap (2021)

- Lunsford, V.W., Piracy and Privateering in the Golden Age Netherlands (2005)

- Meier, D., Seefahrer, Händler und Piraten im Mittelalter (2004)

- Näsman, U., Raids, Migrations, and Kindoms. The Danish Case (2000)

- Naum, M., Re-emerging Frontiers: Postcolonial Theory and Historical Archaeology of the Borderlands (2010)

- Nedelius, S., Early Germanic Dialects – Old Frisian (2019)

- Neumann, G., Namenstudien zum Altgermanischen (2008)

- Nieuwhof, A., The Frisians and their Pottery: Social Relations Before and After the Fourth Century AD (2021)

- Paine, L., The Sea and Civilization. A Maritime History of the World (2014)

- Pearson, A.F., Barbarian Piracy and the Saxon Shore; A reappraisal (2005)

- Renswoude, van O., De Huigen en het Humsterland (2022)

- Renswoude, van O., Namen van Nederlandse stammen: Frisii (2012)

- Rowley, S.M., The Old English version of Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica (2011)

- Schokkenbroek, J. & Brugge, ter J. (eds.), Kapers & Piraten. Schurken of helden? (2010)

- Schrijver, P., Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages (2014)

- Shippey, T., Beowulf and the North before the Vikings (2022)

- Siefkes, W., Ostfriesische Sagen und sagenhafte Geschichten (1963)

- Sijs, van der N. , Geleend en uitgeleend: Nederlandse woorden in andere talen en andersom (1998)

- Simpson-Housley, P., The Arctic: Enigmas and Myths (1996)

- Spiekhout, D., Nijdam, H. & Dijk, van C., Mith egge and mith orde. Tweesnijdende zwaarden uit Friesland en Groningen vanaf de prehistorie tot in de late middeleeuwen (2023)

- Tschan, F.J., Adam of Bremen. History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen (2002)

- Tuuk, De Franken in België en Nederland. Heersers in de vroege middeleeuwen (2016)

- Violatti, C., The Saxons. Definition (2014)

- Vries, de J., Wat hebben Jacob Benckes en Robinson Crusoe gemeen? (2020)

- Westerdahl, C., The maritime cultural landscape (1992)