The peoples of islands and archipelagos don’t let others dictate how to live their lives. One of those archipelagos that meets these criteria as well is the Wadden Sea. For centuries, it’s from here that sea explorers, tax evaders, sturdy Arctic whalers, self-righteous women, pirates, privateers, and other vagabonds came from. An archipelago which the Sea Beggars and the earliest trouser-wearing women call home. Even the first atheist of modern times comes from this archipelago. When Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands launched the ambitious LancewadPlan initiative in 1999 to preserve the common cultural landscape and local identity of this archipelago, we’re not sure if our wise policymakers had this part of heritage in mind. Time, therefore, to tell the real story of the inhabitants who live here. A story of une civilisation de l’eau.

1. Its landscape

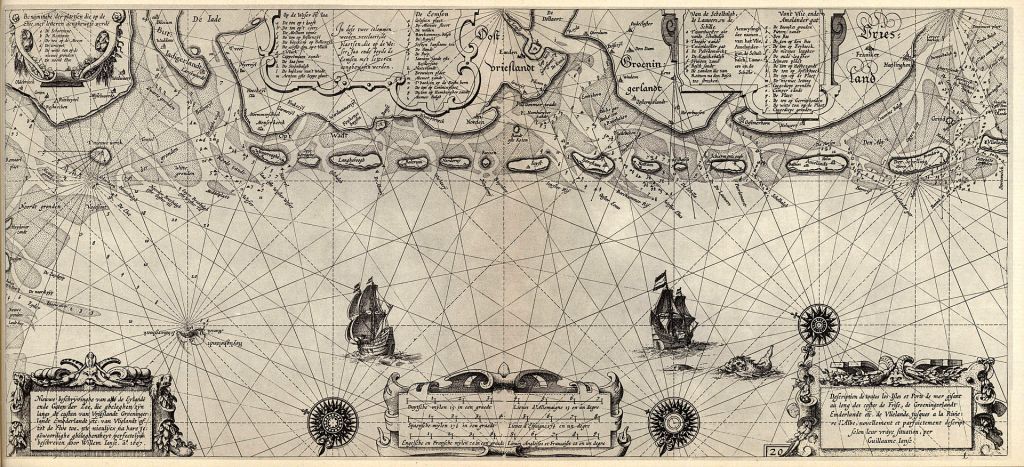

Not every Dane, Dutchman or German might be fully aware, but their islands are part of an archipelago much bigger than their national borders. And it’s quite huge. It has a length of approximately 500 kilometers. Total surface is about 22,000 square meters, which includes the Wadden Sea proper, its islands, and the adjacent coastal zone. In total, and currently, there are fifty-two islands and sandbanks. Recognizing that the difference between an island and a sandbank is a gradient one. These islands are barrier islands with sand beaches facing the North Sea, and marsh islands called Halligs. Often, barrier islands are partly wooded. The Halligs have no dunes to protect themselves during storms, and regularly are being flooded. The salty environment prevents trees from growing on these salt-marsh islands. Hence the typical flat, barren green appearance.

Of the fifty-two islands, Halligs and sandbanks, only twenty-eight are inhabited. About 81,000 islanders in total. Below, at the end of this post, we’ve listed all fifty-two islands, Halligs and sandbanks. Of course, there’s also the red, rocky island of Heligoland (also Helgoland) in the German Bight. Although it’s part of the earliest history of the peoples of the southern rim of the North Sea, it’s not part of the Wadden Sea archipelago as such. Lastly, we didn’t bother to list the many peninsulas along the coast.

UNESCO World Heritage List – The Wadden Sea is recognized by UNESCO, together with 217 other natural sites, as world heritage. First, in 2009, the Wadden Sea area of Germany and the Netherlands, and in 2014 the Wadden Sea area of Denmark. The Wadden Sea is the biggest interconnected inter-tidal area of the world. It’s unique for its migratory birdlife, its strong tidal dynamics, erosion and sedimentation, and it’s geological young because through these natural processes it renews itself continuously (Hilbers 2019).

Another one of the world’s largest tidal marshland of Banc d’Arguin off the coast of Mauritania in the northwest of Africa. Like the Wadden Sea, it is also UNESCO-protected. Both intertidal flats are not just connected on blue United Nations paper, but also in real life through the many seasonal migrating bird species (Beintema 2023).

The main habitats on the mainland are, low-lying lands consisting of tidal marshlands, embanked land called polders (both former saltmarshes and peatlands), bog or peatlands and geests, i.e. sandy, more elevated grounds. This besides the sea itself, which covers about 7,500 square metres. The archipelago has many names in different regional languages. It’s called Vadehav, Waad, Waadsee, Waas, Wad, Wadden, Waddenzee, Watt, Watten, Wattenmeer. The name derives from the Latin word Vadum which means ‘to wade’ or ‘where water can be forded’. It’s a shallow sea and characterized by a strong tide, twice a day, with about two meters difference. So, every six hours much of the sea floors falls dry. Or, if you like, every six hours the land is flooded. The latter is how most Frisians like to think of it.

The archipelago is extremely dynamic. Nothing is made of rock, so everything is constantly on the move due to the wind, sea currents, and the many rivers that flow out into this sea. The sea floor, with its shifting creeks and gullies, changes constantly. Dunes on islands grow and reduce. Islands literally walk from west to east, about two meters per year. That is, if you would let them. Island Schiermonnikoog, for example, grows steadily on its eastern side. It walks from province Friesland into province Groningen, causing the provincial border officially being adjusted several times already. Islands disappear, islands emerge. They split and (re-)unite.

Latest island additions are Kachelotplate (from French cachelot meaning ‘sperm whale’) in Germany, and Zuiderduintjes in the Netherlands. Kachelotplate was declared an island in 2003 when the sandbank wasn’t being flooded anymore during (normal) high tide. Zuiderduintjes was declared an island only last year, in 2020. It’s foreseen that a shower party will be organized for yet another new barrier island soon. In Germany this time. Just west of the small islands Nigehörn, Scharhörn and Neuwerk.

And island Ameland in the Netherlands is on the brink to lose its ferry connection with the mainland because the process of silting up of the fairways is too strong to be kept up with continuous dredging. Plans are being made to relocate the ferry harbour on the mainland more to the west, from the village of Holwerd to the hamlet of Zwarte Haan.

In other words, an ever-changing environment. It has always been like that. A landscape being a result of more than 3,000 years of interaction between humans and nature. During the Late Middle Ages, the landscape of the Wadden Sea changed dramatically again, after many severe storms and great floods. It was during this period that many bays and inland seas emerged, like the Dollart Bight, Leybucht, Harlebucht, Jade Bight, and the estuary of the River Eider. Furthermore, most of the coast of Nordfriesland was washed away. The scattered islands you can see there today, are the remains of that former coast. If one takes a glance at the old Frisian sagas, these are full of stories about lost lands, settlements and drowned people. At the same time, other bays and inland seas started to silt up and gradually turned into land. Take for example the bays of the (former) rivers Ahne, Borne, Fivel, Lauwers, Harle, Hethe, Hunze, Marne, and the bays near Campen and Sielmöncken. Also, large parts of the Dollart Bight have been reset from sea to land.

On top of great tragedies during floods and dyke breaches, great loss of life happened while working at sea too. Illustrative is the storm during the night of March 5-6 in 1883. The fishing fleet of the tiny village Peasens-Moddergat lost that night seventeen of its twenty-two ships. Eighty-three men died. Thus, almost the entire adult male population of a village wiped out in single night. Sixty-six women became widow overnight. Peasens-Moddergat was only one of many fishing villages hurt by this storm. It was only one out of many storms.

Besides being the tallest people of the planet (find out more about the features of the inhabitants in our post Giants of Twilight Land), the people of the Wadden Sea archipelago developed several techniques to survive in this volatile landscape. At first, around 2,600 years ago, people raised mounds to live on, the so-called terps. These can be found everywhere along the Wadden Sea coast. Consult our Manual Making a Terp in 12 Steps to get a deeper insight in this curious phenomenon. Know at least, that more soil has been piled up along the Wadden Sea coast to make terps, than for building all the pyramids together in Egypt. And that without making use of slaves, and without having a ruler or government to organize it top down. It was, literally, bottom up.

Around the year 1000, the coastal people started to build serious dykes to block the sea from the land entirely. At first in Germany and the Netherlands, and from mid-sixteenth century onward also in Denmark. Besides blocking the sea, they soon started to reclaim land from the sea too. This reclamation process continued until only a few decennia ago. It all resulted in the biggest earth and woodwork made by hand mankind has ever witnessed to see. A man-made structure of dykes, sluices, ditches, waterways, and of windmills connected with each other along the Wadden Sea coast, and often referred to as the Golden Ring. The ancient regions Midachi (modern area of Middag) and Hugumarchi (modern area of Humsterland) in the west of province Groningen are even considered the be the oldest cultural landscape of Europe. Read our post Out averting the inevitable a community was born to learn more in depth what the Golden Ring is all about.

Lighthouses – If terps, dykes and windmills does not work for you, maybe lighthouses do. The Frisia Coast Trail is the place to be when it comes to lighthouses and beacons of light. In total you can spot 143 of these, of which a staggering 88 in the Wadden Sea region. Hiking the Frisia Coast Trail by night is easy: just follow the light. On our Trail Map we have added a layer where to find all 143 lighthouses.

At the same time, the massive peat exploitation of the adjacent interior and embankment of the salt marshes all along the southern North Sea coast, from more or less the tenth century onward, meant that the Frisians living along the Wadden Sea coast in the Netherlands and Germany, lost much of their maritime culture (De Langen & Mol 2021). The sea was blocked by high dykes and agriculture thus became a more prominent economic activity. At the same time, peatlands were dug away massively, with the effect that the old Frisian lands were no longer separated from the mainland by its historic impenetrable zone. The ancient twilight zone of land and sea became more land and less sea.

2. Its men

To really appreciate the characteristics of life in the archipelago, one must realize the Wadden Sea has much in common with other archipelagos in the world. A first obvious similarity is how its peoples deal with taxes. In essence, islands and archipelagos are tax havens. Take for example the Bahamas, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, the Cook Islands, Guernsey, Jersey, Mauritius, Saint Kitts and Nevis, the Seychelles, and the Virgin Islands. All islands ranking in the top of world’s tax havens. But the Netherlands also raises eyebrows with its number 4 ranking on the Corporate Tax Haven, and number 8 on the Financial Secrecy Tax Index. Considering the relatively many Wadden Sea islands, but also the many (former) islands of province Holland and Zeeland, and considering the maritime-capitalistic heritage, their top ranking shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. Read our post Porcupines bore U.S. bucks about the birth of economic liberalism in the Early Middle Ages, indeed on this very same coast.

Plata o plomo, either your plata ‘silver’ or our plomo ‘lead’ – i.e. bullits. From tax havens and an obsession with money, it’s only a small step to piracy. The Wadden Sea, in fact, is already for the most of the last 2,000 years a nest for pirates. Even the common cultural origin of the Wadden Sea might be one of piracy. Read our post It all began with piracy to understand how this buccaneer-culture emerged during Late Antiquity, and to learn why the English and Frisian languages are much related.

The sea straits between the Wadden Sea islands were strategic spots, like the Boorne between islands Terschelling and Ameland, or Scholbag between islands Ameland and Schiermonnikoog. Ships with cargo of the Hanse trade had to pass through these straits. Different local headmen, haadlings in Mid-Frisian language, exercised control over islands and the straits in between during the Late Middle Ages. On most islands, near the straits, they had built fortified towers, called a werk, annex small castles of stone, called a steenhuis or stins ‘stone house’. Besides profiting from the sea trade, fisheries and the so-called strandrecht ‘beach right’, which gave them rights on stranded cargo, these headmen also directly profited from piracy and even sheltered them for their own advantage. This much to the irritation of the cities of Bremen and Hamburg, for example. These cities built their own strongholds on islands, like on the island Neuwerk (Feenstra 2023). Neuwerk can therefore be translated as ‘new castle’.

Again, the Wadden Sea archipelago isn’t unique. Other former well-known nests are the Caribbean, Dunkirk (also dubbed Algiers and Tunis of the North), the Barbary ‘Berber’ Coast, the Bab el-Mandeb ‘gate of tears’ at the Red Sea, the Strait of Hormuz, the Philippines archipelago (the famous Iranun and Balangingi pirates), the Sulawesi islands, the coast of Borneo (the Iban or Sea Dayak pirates), the Straits of Malacca (the Orang Laut ‘sea people’ pirates), the Riau-Lingga archipelago and Malay Peninsula (the Bugis pirates), the coasts of Japan, Korea and China (the Wako pirates), and, of course, the coast of Somalia up to very recently (Lehr 2019). And, obviously, infamous pirate ports like Nassau, Port Royal, al-Jaza ir (Algiers), Macao and Tortuga. Ports that speak to the imagination. Looking further back in time, ancient Greece was known for its pirates in the Greek archipelago too. The word ‘pirate’ is even derived from the Greek word peiratēs, meaning something like ‘to attack’.

During the golden age of piracy, many Dutchmen went a-pirating in the Caribbean, the Golf of Mexico, and the Barbary Coast. The latter being the modern coast of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. Some of their names are Claes Compaen, Siemon Danziger (alias Simon Reis) also known as Simon Danziker, Zymen Danseker also known as Simon the Danser, Ivan Dirkie de Veenboer ‘peat farmer’ from Hoorn (alias Soliman Rais or Süleyman Re’is), Jan Jansz. (alias Murad or Murat Rais the Younger), the infamous Rock de Braziliano or Roche Brasiliano, general Laurent de Graff or Laurens de Graaf (alias Lorenzillo), Ghyslain du Plessis (alias Pierre Le Turcq), Nicolas Jarry, Nicholas van Hoorn, Christen Nyegaard (alias Christiaan Cornelis). Ivan Dirkie de Veenboer even became commander of the great Barbary pirate fleet, and explains how he got his name Soliman Rais. The title re’is or rais, by the way, is Arabic for ‘captain’. Apart from the fact that Rock de Braziliano, who originated from province Groningen, and his men were known for their extreme cruelty, they also lived the merry life. After having captured a Spanish treasure ship in the Caribbean, they spend all their new fortune on sex and alcohol in brothels and bars, in only a few days time (Lehr 2022).

Also the Pechelingues were an infamous bunch roaming the Caribbean. Pechelingues, or Pixaringos, was a bastardization of the word ‘Vlissingen’, the port in province Zeeland commonly known as Flushing. Read our post True Pirates of the Caribbean, to appreciate these pirates from Vlissingen/Flushing. But many, many more men from the Republic sailed under the Jolly Roger, although not very widely known since mostly English and American pirates made it into the history books and novels. An important reason why Dutch pirates with their snauws and frigates were omnipresent during the golden age of piracy, is that the authorities of the Republic heavily relied on vrijbuiters ‘freebooters’, a word of Dutch origin, and pirates as a means of warfare. Besides, the Republic had by far the biggest maritime fleet the world had ever seen hitherto. To give an impression. By the year 1676, the maritime fleet of the Dutch Republic had grown to 900,000 tonnes. When compared to Engeland with 500,000 tonnes and to France with 100,000 tonnes, it was of a spectacular size (Christensen 2021).

Barbary or Salé pirates based in northern Africa also operated in the waters of the British Isles. Even all the way to Iceland. In 1625, these pirates took over the island of Lundy in the Bristol Channel and abducted all inhabitants. The barbary corsairs allegedly flew the Ottoman flag over the island. It was Jan Jansz. alias Murat Rais the Younger, a Salé/Barbary pirate of Dutch origin, who used Lundy Island as his base during raids in the wide region. In 1627, for example, he raided Iceland and captured four hundred slaves. In 1631, he raided Baltimore in Ireland, where he captured a hundred slaves. Five years later, there were still reports of Turkish pirates at Plymouth, Barnstable and Southampton (Boyle 2016).

That the threat for a sailor of being enslaved was real, becomes evident when looking at the statistics. Over the period 1520-1660, Barbary corsairs captured in total 420,000 Europeans as slave. Furthermore, estimations are that between the years 1520 and 1830 about 750,000 Europeans were sold as slave in the city of Algiers. If the European slaves sold in Libya, Morocco and Tunis are add up, the grand total must have exceeded the million (Doedens & Houter 2022). Another, higher estimation is that between 1530 and 1780 certainly a million, but quite possibly one and a quarter, white slaves were taken by the Barbary corsairs (Davis 2003). Many European captives were deployed as galeotti ‘galley slave’ on the corsairs galleys, or otherwise put to work on construction sites, in stone pits, or as labour in agriculture etc.

Barbary Coast in San Francisco – The infamous name of the Barbary Coast of northern Africa survived, and popped up on the shores of the Pacific Ocean a century later. During the Gold Rush in California in the nineteenth century, San Francisco developed from a backwater into a city in no time. With all the male gold diggers, and the money they earned, demand for prostitutes was high. The area around Front Street was a place of bars, gambling houses, whore houses, dance halls and much more. Crowded by thieves, gamblers, low women, drunken sailors, and prostitutes. In order to meet the demand for sex, prostitutes were brought in from Mexico, France, and all the way from China. “The Barbary Coast is the haunt of the low and vile of every kind,” as it was described back then (Cordingly 2001).

It was in November 1856, that the clipper Neptune’s Car entered the port of San Francisco. Acting captain was a woman, Mary Patten. She was the wife of captain Joshua Patten who got ill, just before they had to sail the dangerous Cape Horn, and it violently stormed. Due to circumstances no-one else could command the clipper, so Mary took over before mutiny started. She had learned to sail from her husband before. And she managed, knowing that Cape Horn is an infamous sea strait. How do you mean, women on ships bring bad luck?

The entire war of independence of the Low Countries against the huge kingdom of Spain had a major effect on the Wadden Sea region, and yes even on the world. Firstly, when the Spanish started to prosecute Protestants and Anabaptists, it led from the second quarter of the sixteenth century onward, to migration flows from Flanders to England, to the provinces Holland and Friesland, and to the county of Ostfriesland (East Frisia). Especially, province Friesland and county Ostfriesland, including their islands, were relatively safe havens from where the Protestant rebellion in the Low Countries continued to be fueled. Both with money and ideology. Ostfriesland was governed by the Protestant count Edzard II.

When in 1568 the war of independence against Spain broke out, which would last for eighty years, an important strategy of William of Orange, the nobleman who led the Bourgeois rebellion, was to issue so-called ‘letters of marque’ to the pirates who were active in region West-Friesland, i.e. the region within province Holland, and in the Wadden Sea archipelago. Of course, the Spanish didn’t recognize William of Orange as a legitimate authority but the Wadden Sea pirates were equally happy to sail with these letters as ‘legal’ privateer. These authorized pirates became known as the Watergeuzen ‘Sea Beggars’, under their motto “liever turcx dan paus” meaning ‘better Muslim than Catholic’.

The word privateer, by the way, is a contraction of private and volunteer. Corsair, another term for authorized piracy, mainly used for the pirates of the Barbary Coast, stems from the Latin word cursarius meaning ‘raider’.

(Water) Geuzen – In 1561 a delegation of nobles demonstrated in Brussels against the Spanish inquisition. They delivered a petition to the palace of Governor Margaret of Parma. Her advisor tried to downplay the situation and assured Margaret they were nothing but a bunch gueux ‘beggars’. The Dutch nobleman Hendrik van Brederode alias Le Grand Gueux, didn’t forget this remark. When he later made toast during a banquette he said: “I drink on the health of the Beggars. Long live the Beggars!” The rest is history.

Heyday of the Sea Beggars was the period between 1569 and 1573. Of all the booty and ransom the Beggars gathered, a third was ceded to William of Orange to finance his costly war on land against Spain. The Sea Beggars were renowned for their cruelties and attacked almost every merchant ship they came across. A red flag was the symbol of the Beggars at sea, and it would remain the flag under which privateers of the Dutch Republic sailed. Important ports of the Sea Beggars were Greetsiel, Leer, Norden, Emden, and the islands Texel, Vlieland, Terschelling, and Borkum. But also the people of the island Schiermonnikoog were known for their saying during heavy storms “eerst roven dan redden” meaning ‘first rob then rescue’. And another well-known seventeenth-century saying of the people of the city of Hamburg was: “Die Lude van Munkeoog bint Rover” meaning ‘the people of Schiermonnikoog are raiders’. As a side remark, among the religious refugees from the south, the code name of island Vlieland was ‘Titan’.

All these places give away the heart of the Beggars operations: the southern Wadden Sea and the county of Ostfriesland. Ports -or should we say pirate’s lairs?- that profited well from the booty brought in and sold. And, not only the ports. The East-Frisian count, Edzard II, also profited directly. La Rochelle, Sandwich and London were also ports where the Sea Beggars docked. Back then already, the mentality of island inhabitants of the Wadden Sea archipelago was known for being wayward and not too passionate to obey rules from the mainland. Anabaptists, however, were very welcomed by the islanders. So, the winds of change could grow freely and stronger at the rim of the Continent.

To a certain extent every Dutch child is indoctrinated at high school how in 1572 the Spanish lost the town of Den Briel, modern Brielle in province Zuid Holland, to the Sea Beggars. It’s celebrated on the first of April every year, with the slogan: “Op 1 april verloor Alva zijn bril” literally translated as ‘on the first of April [duke] Alva lost his glasses’. The word bril must be understood as ‘Den Briel’, but also means in modern Dutch ‘glasses’. But it’s not celebrated by everyone. Primarily celebrated by Protestants, and not by Catholics. For the Sea Beggars were Protestant. Be this as it may, the capture of Den Briel is being considered the turning point in the war of independence against Spain. What isn’t always told during history lessons at school, is that the Beggars basically were, as described above, a bunch of cruel pirates. Nor is being told that the Beggars were, in fact, preparing a raid in the Wadden Sea area, when the wind blew them off course from the port of Sandwich, England. Only by change they ended up at the town of Den Briel. The Spanish, logically, taken by surprise, and the ‘victory’ boosted the strife for independence. Your classic butterfly effect.

As a side note concerning the sensitivities between Protestants and Catholics, to this day people remember that shortly after the liberation of Den Briel nineteen Catholic clergymen were brutally murdered by the Sea Beggars. February 2022, the municipality designed a walking tour called ‘Beggars and Martyrs’ leading through the modern town of Brielle (Onnink 2022).

Notwithstanding the capture of Den Briel dominates history lessons, the real strategic significance of the Sea Beggars was that they controlled the important sea channels of the Wadden Sea. In particular, the straits of Marsdiep and of Vlie. Marsdiep is the channel between the island of Texel and the mainland of province Holland. Vlie is the channel between the islands of Vlieland and Terschelling. The economy of Amsterdam, and the whole of region Holland for that matter, relied on the trade going through these two sea gateways. Controlling these, as the Sea Beggars did already before the war of independence broke out, had a major economic impact and was felt in Madrid by the Spanish Crown. Converted to today’s buying power, the Beggars damaged the economy with tens of millions of euros, and thus supplied the rebellion with significant funds. Not only did it cost Madrid money, the Sea Beggars also put their hands on grain supplies, which was crucial to feed the fast-growing population of Amsterdam. Therefore, the key for the resistance against Spain wasn’t controlling the River Meuse where Den Briel was located, but controlling the straits of the Wadden Sea (Doedens & Houter 2018).

An important trade going through the strait the Vlie was the so-called Baltic Sea navigation, also called Grote Oost ‘big east’, Oostzeevaart ‘east sea navigation’, or the Sontvaart, i.e. the sea trade passing through the Sound Channel between Denmark and Sweden. Grain and wood was the main cargo of this trade. For long, the Hanseatic League, led by the city of Lübeck dominated this navigation. The typical ship the Hanseatic merchants used was the cog ship, also kugg or kogg(e), which had an enormous carrying capacity. Eight or ten times more than that of its predecessors. The cog ship was developed by the Frisians, traditionally the freighters of the wider North Sea area (Westerdahl 1992). This clunky ship type came into use at the end of twelfth century and stayed in use until the fifteenth century, when it was surpassed by the hulk ship type. The hulk would stay popular till the seventeenth century. In the late ’70s of the last century, the Hulk made its comeback with Bill Bixby and Lou Ferrigno.

Less important than the Baltic Sea navigation but still relevant, was the Arkhangelsk navigation. Arkhangelsk is a town located at the mouth of the River Dvina in Russia, at the White Sea. Again, skippers originating from the Wadden Sea islands were well represented, especially those from the island of Vlieland. Over the seventeenth century, in total 2,800 times ships from the Republic sailed to Arkhangelsk, of which 575 skippers from Wadden Sea islands (Doedens & Houter 2022).

As an interesting aside, the Dutch word vracht for ‘freight’ is of Frisian origin, just like the word eiland ‘island’ meaning ‘water land’. Between 1000 and 1200, these words found their way into western Dutch language, which can be understand in connection with the important role Frisians played in the water trade in north-western Europe from the Early Middle Ages and beyond (De Vaan 2014). Another, later in time between 1600-1800, interesting fact was that skippers from province Friesland, i.e. the port towns of Harlingen and Hindeloopen, and from the islands Terschelling and Vlieland, dominated the Baltic Sea navigation. Island Vlieland and the city of Danzig, modern Gdańsk in Poland, even have very special ties. Many people from especially island Vlieland, but also many others from Friesland, emigrated to Danzig in the second half of the seventeenth century (Doedens & Houter 2022).

It was Amsterdam that broke the Hanseatic League and the domination of the Wendish cities during a series of -indeed- privateer wars between 1426 and 1441. The Low Countries started to trade with the Baltic Sea in fourteenth century, on ports like Reval (Tallinn), Riga, Memel (Klaipéda), Libau (Liepaja), Koningsbergen (Kaliningrad), Pernau (Pärnu), and Danzig (Gdansk). The Hanseatic League had always relied on protectionism, whereas the Frisians and later the Dutch, were as long as one can remember hardliners in the principles of free trade and of mare liberum ’free sea’. Read our post Porcupines bore U.S. bucks to understand the true birth of the international free trade and capitalism. After the Hanseatic League was forced on its knees, the Dutch share of the navigation going through the Sound Channel increased spectacular. To give an idea: from fifty percent around the year 1500, to seventy percent in 1600. By then, the share of the Hanseatic cities was as low as seventeen percent.

Foundation of the Dutch and English Navy – On June 13, 1570, the Frisian Jan Baes (also known as Jan Basius) from the town of Leeuwarden in province Friesland, instructed by Prince William of Orange, makes an agreement with three captains of the Watergeuzen ‘Sea Beggars’. They agreed to co-operate, in service of William of Orange, against Spain and all who was pro-Spanish, and to harm them as much as possible.

Therefore, the presence of the Sea Beggars in the Wadden Sea can be considered the foundation of the Dutch Navy. The agreement said:

“Seckere articulen tusschen cappiteijn Troij, Ruychaver ende Adriaen Menninck geaccordeert, waarop sy tot dienst van onse genadighe heere de prince van Oraingien, Grave tot Nassou te watere ofte te lande bijde ende met haer sullen laeten gebruijcken.“

England often dates the establishment of its navy in the year 896, when king Alfred of the kingdom of Wessex had built long-ships to oppose the esks ‘warships’ of the Vikings. These ships, with 60 oarsmen, were built neither on the Frisian neither on the Danish pattern, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle quotes. Furthermore, during the maritime confrontations between the Danes and the army of Alfred at the Isle of Wight that same year, the Frisians named Wulfheard, Æbba and Æthelhere were killed, together with 62 more Frisians. On Danish side 120 men were killed.

What it all makes clear, Frisians with their seafaring skills were actively recruited by king Alfred to establish a naval force. Both to built warships, and to man them. King Alfred’s use of Frisian craftsmen and maritime warriors is perhaps connected with the alliance with the Franks and especially with Baldwin II, margrave of Flanders, who married Alfred’s daughter Ælfthryth (Williams, Smyth & Kirby 1991). Read also our post A Frontier known as Watery Mess: the Coast of Flanders.

In other words, if you’re in need of a proper navy, have Frisians it organized for you.

Check also our post They want you as a new recruit.

The hegemony of the Sea Beggars over the Wadden Sea also meant new opportunities for the islanders. The number of islanders, notably from islands Vlieland and Terschelling, registered in the toll records of the Sound Channel, increased strongly. More in general, it gave Frisians advantages which lasted up to the eighteenth century. A period when Frisian skippers became (again) known as the freighters of Europe for their huge share in the Baltic Sea navigation. In fact, this was a continuation of the maritime trade Frisians were involved in already throughout the Middle Ages. With their existing networks, and commercial and maritime knowledge, they were able the scale up their share in the trade. And they profited a lot with the economic rise of the Republic and its growing population. Only with the occupation of the French at the end of the eighth century, this trade suddenly came to an end and was never able to recover from it (Koopmans 2020). A turning point in the history of the Frisians, from being a sea culture to an agrarian society.

resumé

Important thing to remember from this whole history roughly outlined above, is that the Wadden Sea archipelago has a very long tradition in piracy. With the rebellion against Spain, not only region Ostfriesland, and in particular Wadden Sea island Borkum (Feenstra 2023), became an important base of the rebels fighting for independence, but the freedom movement got intermingled with the already existing freebooter culture in the Wadden Sea. Pirates transformed into the Sea Beggars, a badge of honor, with their ports in the county of Ostfriesland and on the Wadden Sea islands. William of Orange opportunistically authorized their brutal raids. That way not only receiving funds to pay for the costly war on land, but also putting pressure on the king of Spain through the blockade of crucial sea channels at the Wadden Sea.

The distinction between pirate and privateer blurred in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Freedom, vrijbuiter ‘freebooter’, mare liberum, independence, equality, and pirates. It explains why during the Republic, authorities were often ambivalent when it came to the sanctioning of proven-guilty pirates. More than once, judges and admiralties sufficed with a lower punishment than the laws prescribed. Even more remarkable, notorious Dutch pirates who had raid Dutch ships and committed all kinds of atrocities against their fellow citizens, repeatably were pardoned and able to resume life in high society, like nothing had happened (Lunsford 2005). The seventeenth-century public also loved the reports and pamphlets that were printed about the fortunes and misfortunes of pirates. And nowhere in the world was the population of a country so literate as in the Republic. It was adventurous. Piracy had become part of the psyche and the republican-identity of the Dutch rebellion culture.

Considering this buccaneer tradition, it’s not too bold to say that it’s no coincidence the first atheist of Europe in modern history originates from the Wadden Sea region. His name is Matthias Knutze (1646-1674), born in the village of Oldeswort in Nordfriesland, Germany. Knutze ‘believed’ only reason and conscience mattered. Besides rejecting the Church, he pleaded that wealth should be distributed equally. Honestly, his ideas would fit any person sailing under the black flag. You’ll find some more clues why all this fits neatly in a buccaneer culture, when we discuss the saga of the pirate Black Rolf below.

Insuper Deum negamus, Magistratum ex alto despicimus, Templa quoque cum omnibus Sacerdotibus rejicientes.

Matthias Knutze

Most of all, we defy God, we despise high authorities, we reject the Church and its priests.

Against this background also, it’s not surprising that distinctive pirates annex warlords like Klaus Störtebeker and Grutte Pier posthumously were knighted as, hold your breath, freedom fighters. Störtebeker was one of the leaders of the Vitalienbrüder ‘Victual Brothers’, also known as the Liekedeelers ‘those who share equally’. Whilst in essence, of course, they were just ordinary bandits. It has obvious parallels with other friendly bandits like Robin Hood and his posse, together with Lady Marian. Not at the bright sea, but in the dark forests of Sherwood this time. Where they robbed the rich and divided the wealth among the poor. Piracy and banditry as an expression against social injustice and a plead for more individual freedom. Piracy as means to an end. Exactly what the thoughts of William of Orange must have been.

Lastly, fittingly the tourist branch in Nordfriesland promotes its region as the Friesische Karibik ‘Frisian Caribbean’ to summon to the piracy past of the archipelago.

3. Its women

During the Hanseatic period, the island of Borkum Island was a well-known pirate’s nest, including the Liekedeeler pirates. Borkum, together with the island of Texel, is somewhat different from the other islands of the Wadden Sea archipelago because it consists partly of boulder clay, and thus remains fixed in their spot. Borkum and Texel do not ‘walk’ from west to east like the other fifty islands.

Borkum is the only island mentioned by the Romans, while Texel was still connected to the mainland. According to the Roman writer Plinius in the first century AD, the island of Borkum, locally known as Burcana, was called Fabaria by the Romans, meaning ‘beans land’ (Looijenga et al 2017). During the Early Middle Ages, Borkum was part of the saltmarsh island Bant, which also included the current islands Juist and Norderney. After severe storms, the island of Bant was shattered into pieces. Small remnants of Bant south of Borkum disappeared into the waves forever in 1781.

Pliny also mentioned two more islands, namely Glaesaria, known locally as Austeravia, and Actania. Glaesaria means ‘glass land’ and is where amber came from. Perhaps, therefore, Pliny spoke of Heligoland. Actania is identified as the island of Terschelling and Austeravia as the island of Ameland (Van der Wal 2007).

There exists a saga in region Ostfriesland about island Borkum, which recounts how its women fought against the famous pirate Schwarze Rolf ‘Black Rolf’. It also helps to explain why its women started to wear trousers. It also, very subtle and indirect, touches upon prostitution. What the saga furthermore nicely illustrates, are the connections of Ostfriesland with the rebellion and piracy of the Republic in its struggle for liberation from Spain. Something Dutch people in general aren’t aware of, and region Ostfriesland never received the credits for.

The Saga of Black Rolf

Black Rolf was one of the most feared pirates of the North Sea. He was named after the great Viking Duke Rudolf. A Viking who died in battle against the Frisians. But Black Rolf also carried a letter of marque issued by the Prince of Orange of Holland. He wore a black beret with a white, seagull’s feather. You were never safe at sea. No matter how hard people tried to hunt him down, he never was caught. He was like a ghost. Like the Flying Dutchman. People said, Black Rolf was never born and could, therefore, never die. His magic made him invincible. In other words, Black Rolf was the Devil, or at least he had made a pact with it.

One day, all the men of Wadden Sea island Borkum had sailed for Greenland to hunt for whales. Therefore, the women were all by themselves. It had given some discussion to leave them all alone, but the women were glad there were half that many mouths to feed. That the island was without men to protect it, came to the attention of Black Rolf when he was with his ship was in the harbour of Delfzijl. It offered an excellent opportunity to raid the island and find some booty. Island Borkum was a desired island. According to legend, the great treasure of the famous pirate of the Liekedeelers Klaus Störtebeker is buried somewhere in the Wolde Dunes of the island. The saying is not without reason:

Wenn de Woldedünen kunnen spreken,

Sull et Börkum noit an Geld gebreken.

If the Wolde Dunes could speak, Borkum would never lack any money.

One of the women, the beautiful maiden named Insa, discovered the ship of Black Rolf when she was searching for bird eggs in the dunes. The black hulk ship lay at anchor near the beach at low tide. Its brown sails lowered, and its dreaded caper flag raised. But she knew him. She had had an affair with him long ago, when he was in the harbor of Greetsiel among the Sea Beggars. But he had betrayed her. “Never again would he have her, nor any other women of the island,” she said to herself.

Insa ran back to the village and alerted the other women with a ship’s bell. Everyone knew what danger they were in. At the same time, a man alone arrived with a boat. It was the young vicar named Christoffer. He also heard the bell and hushed toward it. He found the women in a heated debate on what to do. Instead of jumping into action, the vicar started to pray. When he next wanted to sing psalms too, it was Insa who said it was enough. She said they did not have the time for all this. Rather, she would like to hear from the vicar if God had shared any thoughts with him on what to do. The vicar urged once more to pray, and Insa prayed with him. Still, the vicar had no advice. Finally, he suggested they should hide themselves in the dunes.

For the women this was not any option. The crew of Black Rolf certainly would find them. After some more discussion among the women, it was again Insa who made them focus again. She proposed to defend themselves and to drive Black Rolf and his men back into the sea. For this they would dress and arm themselves like men. Everyone agreed and exclaimed: “Eala Frya Fresena!” The vicar tried to convince them not to go to battle because that was not something women should do. He was completely ignored.

The women grabbed clothes of their men and put these on. Also, with all the strength they had, the women rolled an old cannon to the beach. With it they managed to hit the mast of the ship. The cannon balls that followed caused a lot of damage to the ship. A fire broke out as well. The ship of Black Rolf was defenseless at low tide. Its cannons rendered useless with an immovable ship, and fleeing was impossible too. Black Rolf was left no choice other than to make peace, if he wanted to avoid shipwreck with his ship adrift in the sea currents. He shouted to the women: “Say what you want but let us go ashore to save our souls!”

The women decided to let the pirates go ashore. But without weapons, and one by one. The pirates agreed. Each man that set foot on the island was tied up and locked up in the tower. Among the crew was also the presumed daughter of Black Rolf, who was, in fact, his lover. The women did not know she was Black Rolf’s lover. She was not locked up and allowed to walk freely on the island. This because she was such a young woman and appeared to be terrified by the whole situation. Black Rolf’s ship was set afire.

That evening all the women went to the tavern of the village to celebrate their victory. They drank, sang, and danced. To enjoy themselves even more, they had brought the cabin boy of Black Rolf to the tavern. Later, they even brought in two more, not too strong, prisoners. Also for the purpose to dance with them.

Insa however, stayed at her house with Black Rolf’s presumed lover. They spoke with each other. The girl appeared still terrified. She told Insa they were not heathen raiders, but Sea Beggars. Fighting with William of Orange against the Spaniards and the Pope. To free the Provinces from the kingdom of Spain. However, Insa did not believe her and replied that Black Rolf was only interested in gold, booty, and women.

When Insa found out the women had freed more men to dance with, she knew things would turn bad if she did not act immediately. She confronted Insa and asked whether she really was Black Rolf’s daughter. The girl lied she was. Insa knew it was a lie and told her she once was Black Rolf’s lover too. Insa also proposed to let everyone free if they would leave the island that same night. The girl agreed.

As the night fell and the island was covered in darkness, Insa and Black Rolf’s daughter freed the men from the tower. The first to come out was Black Rolf. He recognized Insa when he saw her and touched her hair with his hand. Insa warded off his hand. She said they had to leave now, and she personally would help them to navigate through the dangerous, shallow sea. The men hurried to the beach to the boat. It was a small boat. With it they set course to sea. Once at sea Black Rolf’s lover asked that Insa, who steered the boat, would be thrown overboard. During the quarrel that followed, they hit a sand bank and got stuck on tidal plate. When the tide came in, everyone drowned.

And that is how women started to wear trousers.

Now everyone knows too why every freebooter movie or novel, the leading pirate always has a woman by his side. Black Rolf already did. Even the famous Frisian writer Simon Vestdijk, who was born and lived his whole live at the port town Harlingen on the muddy shores of the Wadden Sea, wrote novels about pirates. One novel is about puritans and pirates. Here too, the pirate ship the Merrimac has a woman aboard, Lady Arabella Godolphin. Together with her noisy parrot.

The saga’s notion of women starting to wear trousers, and specifically in this region and in this era, isn’t unfounded. Research into women dressing in men’s clothing revealed this did happen in the Dutch Republic during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These women pretending to be men, often enrolled as soldier or sailor. Mostly they were lower-class women and between the age of 16 and 25 years. Sometimes they were unmasked within a few days, but there are also cases of women functioning as men for many years on end, like Catharina Rosenbrock (12 years), Maria van Antwerpen (13 years) and Isabella Clara Geelvinck (15 years). One woman we must mention too, is Maria ter Meetelen. Born in 1704 and from the town of Medemblik in region West-Friesland. She travelled in men’s clothes all the way to Spain and enrolled in a regiment of Frisian dragoons.

Underlying reasons for their travesty are difficult to ascertain retrospectively, but better economic opportunities to survive, patriotism, to stay with her loved-one, more physical and social freedom, and, of course, transgender and homosexuality in itself, all may have been reasons. Also, women were active in the seventeenth-century criminal underworld of Amsterdam, notably involved with extortion and theft. Disguising as men, often was part of the modus operandi. Finally, a significant number of the female cross-dressers in the Dutch Republic in the seventh century, originated from the region Westphalia and the northern German cities Emden and Hamburg. More in general, the phenomenon of travesty between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries is recorded in especially north-west, protestant Europe. Explanation for this is that the marriage age of women was considerably older, and women enjoyed relatively more social and economic freedom than elsewhere in Europe. At the same time, and associated with their more independent position, women were much more vulnerable here. Their vulnerability was furthermore worsened due to the sizable migration in this period. Lastly, in a catholic society there was always the option of acceding to the monastery. In the protestant world this option no longer existed (Dekker & Van de Pol 1989).

For an elaborate overview of women cross-dressing as men in the early modern period, see our post Harbours, Hookers, Heroines and Women in Masquerade.

Back to the saga of Schwarze Rolf. Besides Insa from Borkum, another East-Friesian heroine made history and should be mentioned. She also came from the shores of the Wadden Sea, from Land Wursten, and named Tjede or Thiada Peckes. Tjede Peckes is historic and lived at the beginning of the sixteenth century, and she was part of women’s movement that opposed the Catholic church concerning the practice of women entering the convent. In the year 1517, Land Wursten, a free farmers republic, came into conflict with the bishopric of Bremen. A contingent of 500 women joined the battle at the Wremer Tief, and it was Tjede Peckes who carried the banner of the Frisians. The battle was lost by the Wurst-Frisians, and Tjede Peckes died in battle, only 17 years old.

The Mid-Frisian peer of Tjede Peckes is Bauck Popma from the Wadden Sea island of Terschelling (Kloek 2013). Bauck Popma, also Poppema, and after marriage named Hemmema, lived at the end of the fifteenth century. Pregnant Bauck Popma defended all alone the state ‘fortified house/small castle’ in the year 1496, against militia from the city Groningen. In the end, she had to surrender the state. In prison she delivered a twin.

Also related to strong women who took up arms, is the saga that long, long ago, the women of the city of Leeuwarden in province Friesland defended the city. This was wen their men had left the city. The enemy was defeated and humiliated. This victory was remembered in Leeuwarden every year on October 28 (Dykstra 1966).

Not only in region Ostfriesland and province Friesland sagas exist of brave and strong women all alone on their island or state fighting against malicious men. Also in region Nordfriesland. Here, the women of island Föhr, who were alone without their men too, came into action twice against Sweden and Russia. With drums, pitchforks and other weapons they managed to scare off the enemy. Like island Borkum, here too all men had left whaling in the Arctic. Read our post Happy Hunting Grounds in the Arctic, where we also give special attention to the unique position of the women of the Wadden Sea islands, when nearly all of their men were most of the year at sea hunting whales, walrus and seals in the ice seas.

With these traditional, romantic images we like to think that in the ports, on the islands and on the coasts where these pirates, privateers, and Sea Beggars stayed, women were lesser bound to conventions. Women who crossed traditional boundaries of good and evil, of belief and unbelief, and even crossed the boundaries of gender, of men and women. Just like those savage pirates crossed boundaries. Sagas like Black Rolf, but also historic female pirates or tars dressed as men, like Anne Bonny, Flora Burn, Jeanne de Clisson, Mary Farley, Sayyida al-Hurr, Grace O’Malley, Mary Jane, Mary Lacy, Hannah Snell, Mary Anne Talbot, Ching Shih, and many more, help us to believe they actually did in the Wadden Sea archipelago.

4. It’s final

We started this post with the LancewadPlan initiative of the countries Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands to protect and conserve the Wadden Sea archipelago, its common landscape ánd culture.

Roughly, this archipelago is about 500 kilometers long. Historically, about 350 kilometers of it can be considered Frisian. The breakdown is as follows.

- The ca. 300 kilometers stretching from island Texel to Land Wursten were historically cultural Frisian, and mostly part of medieval political Frisia. Today, the name Provincie Friesland, Region Ostfriesland and Landkreis Friesland testify of this joint political history.

- The ca. 100 kilometers of Landkreis Nordfriesland are historically cultural Frisian too, although it was never really part of political Frisia. It variously ‘belonged’ to Denmark and Prussia.

- The ca. 50 kilometers between Land Wursten and the peninsula Eiderstedt, are Ditmarsian annex Saxon. Dithmarschen and Frisia were, however, cultural much related. Especially concerning the lordless High Middle Ages, when both were a conglomerate of free, peasant republics. Uniquely for Europe.

- Lastly, the ca. 50 kilometers stretch between island Sylt and island Fanø is cultural Jutish.

So, the Wadden Sea area is of origin 10 percent Saxon, 10 percent Jutish, and 80 percent Frisian. We are still double checking the LancewadPlan policy documents to discover the words Ditmarsian, Frisian or Jutish. We clearly missed it while reading, but it must be in it somewhere. It simply must. Like many subsidized European policy initiatives, LancewadPlan washed out in oblivion too, after 2007. Can you imagine a FrisiawadPlan, with this common history in mind?

Note 1 – The twenty-eight inhabited islands and Halligs of the Wadden Sea are:

Wieringen, Texel, Vlieland, Terschelling, Ameland, Schiermonnikoog, Borkum, Juist, Norderney, Baltrum, Langeoog, Spiekeroog, Wangerooge, Neuwerk, Pellworm, Nordstrand, Halligen Hooge, Hallig Langeness, Hallig Oland, Hallig Gröde, Halig Nordstrandischmoor, Hamburger Hallig, Amrum, Föhr, Sylt, Rømø, Mandø, and Fanø.

The twenty-four uninhabited islands and Halligs are: Rif, Engelsmanplaat, Simonszand, Zuiderduintjes, Richel, Griend, Noorderhaaks or Razende Bol, Rottumerplaat, Rottumeroog, Lütje Hörn, Kachelotplate, Memmert, Minsener-Oldoog, Alte Mellum, Großer Knechtsand, Nigehörn, Scharhörn, Trischen, Hallig Habel, Hallig Süderoog, Hallig Südfall, Hallig Norderoog, Langli, and Koresand. See the map for the locations of the uninhabited islands.

Note 2 – In the summer of 1971, in imitation of an initiative of the Danish radio, broadcaster VARA asked two Dutch writers to stay for a week all alone on the uninhabited island Rottumerplaat. The program was called Alleen op een eiland ‘Alone on an island’. It were the renowned writers Jan Wolkers and Godfried Bomans. Bomans stayed on the island from 10-17 July. He mainly sat on a chair and gazed into the distance. Bomans concluded, you don’t need an island to be alone. That can very well be achieved in your own house. However, Bomans felt afraid and vulnerable, which also might have had to do with threats from the Rode Jeugd ‘Red Youth’ earlier, a radical communist movement. Jan Wolkers stayed on the island from 17-24 July. He was very alive. Rushing over the island stark naked, fishing, collecting flowers etc. He had time too little.

If you think staying all alone at the rim of the Wadden Sea and of civilization is a modern thing, think again. Already in the year 1610, Jan Cornelis Femmesz. made a bet with Thomas Thomasz. to cultivate the barren sandbank Bosch (also called Kamperzand) between the islands Terschelling and Ameland, without any help from outside. He would have stay on the sandbank a whole year. On June 11, Femmesz. arrived on the sandbank and on June 13, a year later in 1611, he returned to the mainland. Femmesz. had won the bet. But narrowly. Especially during the night of November 30 and December 1, the flood came so high it almost washed away his little wooden shack. He had already tied himself to some wood to survive. His endeavour aroused a lot of public attention. Already then, “living in solitude at the fringes of the North Sea was generally considered to be an unusual and disturbing experience” (Dykstra 1895, Knottnerus 2005).

Note 3 – The suffix –each, –ø, –oog, and –ooge all mean island (check also our post 10 words to travel 1,500 years and miles acros the Frisian shores). See map for the uninhabited islands. There’s an –oog which is located just outside the Wadden Sea, namely Callantsoog. It’s located in the north of province Noord Holland. And yes, it was once an island and part of Frisia too. The word hallig might be related with the Old English halh, which meant ‘elevated ground surrounded by low-lying marsh’. In the sixteenth century the tidal marshlands were called Halgenland.

Note 4 – Some names of Sea Beggars:

Focke Abels, Jan Abels, Hendrick Arentsz. from Dokkum (alias droncken Heyntje), Adriaen from Bergen (also known as Dolhain), Willem Blois van Treslong, Hendrik van Brederode, Lancelot van Brederode, Volkert Jansz. Cattendijck, sexton Hendrick Claeszn., Jan Claesz. from Sneek, Claes Cornelis, Johan Dambricourt, Jaques le Duc, Jelle Eelsma, Siewke Eminga, Bartold Entens, Gislain de Fiennes tot De Bergues (also known as the Lord of Lumbres), Willem Fransz., Cornelis Meynert de Fries, Seger from Gorcum, Geerlofsz., Pibo from Harda, Jelmer Jelmersz. (also known as Jelmer from Ameland), Pieter from Leeuwarden, Willem II van der Marck Lumey, Jan Martsz., Adriaen Michelsz. Menninck, Nagtegael, Willem from Oldenburg, Derick Poppe, Wigbolt Ripperda, Roobol, Nicolaes Ruychaver, Wijbe Sijwerts, Peter Smydt, Diederik Snoei (also known as Dirck Sonoy), Guilliaume de Terne, Wibo Tjarrels, Jan Jansz. van Troyen (also known as Troij), Ellert Vliechop, Pieter Jansz. from Westerlee, and Dirck Witteloo.

Note 5 – Other blog posts dealing with the common culture of the southern coast of the North Sea in the early modern period are: An ode to the Haubarg by the green Eiderstedter Nachtigall, Happy Hunting Grounds in the Arctic and Harbours, Hookers, Heroines and Women in Masquerade.

Suggested music

- Children’s song, Daar was laatst een meisje loos (1775)

- Kinderen voor kinderen, Op een onbewoond eiland (1981)

- Rob de Nijs, Jan Klaassen was trompetter (1973)

Further reading

- Beintema, N., Een kleine beurs met grote gevolgen (2023)

- Borsboom, M. & Doedens, A., De Canon van de Koninklijke Marine. Geschiedenis van de zeemacht (2020)

- Boyle, P.J., The Archaeology of Lundy Pirates: A Case Study of Material Culture (2016)

- Brouwers, L.L., De vrije heerlijkheid. Amelandgedichten (2013)

- Bunt, van de A., Wee de overwonnen. Germanen, Kelten en Romeinen in de Lage Landen (2020)

- Christensen, A.N., Maritime connections across the North Sea. The exchange of maritime culture and technology between Scandinavia and the Netherlands in the early modern period (2021)

- Cordingly, D., Women Sailors and Sailor’s Women. An Untold Maritime History (2001)

- Davis, R.C., Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters. White slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800 (2003)

- Deen, M., De Wadden. Een geschiedenis (2013)

- Dekker, R. & Pol van de L., The Tradition of Female Transvestism in Early Modern Europe (1989)

- Denekamp, N., Alleen op een eiland. Godfried Bomans en Jan Wolkers op Rottumerplaat (2015)

- Doedens, A. & Houter, J., De Watergeuzen. Een vergeten geschiedenis (2018)

- Doedens, A. & Houter, J., Zeevaarders in de Gouden Eeuw (2022)

- Dykstra, W., Uit Friesland’s volksleven. Van vroeger en later (1966)

- Emanuel, J.P., Black Ships and Sea Raiders. The Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Context of Odysseus’ Second Cretan Lie (2017)

- Engelkes, G.G., Der schwarze Rolf (1937)

- Feenstra, H., Hoofdelingen, kloosters en economie in het Waddengebied (2023)

- Gelder, van R., Het Oost-Indisch avontuur. Duitsers in dienst van de VOC (1600-1800) (1997)

- Grundner, T. (ed.), The Lady Tars. The Autobiographies of Hannah Snell, Mary Lacy and Mary Anne Talbot (2008)

- Haan, de A.C. (ed.), Roeiend redden. Het roeireddingwezen van Texel tot Rottum (1976)

- Hilbers, D., Wadden. De Natuurgids (2019)

- Holm, S., Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte des Walfangs der Nordfriesen (2003)

- Jansen, M. & Oostendorp, van M., Taal van de Wadden (2004)

- Kloek, E., 1001 vrouwen uit de Nederlandse geschiedenis (2013)

- Knottnerus, O.S., Culture and society in the Frisian and German North Sea Coastal Marshes (1500-1800) (2004)

- Knottnerus, O.S., History of human settlement, cultural change and interference with the marine environment (2005)

- Knottnerus, O.S., Van Waddenland tot Waddenzee, of: Hoe de dijk tot scheidslijn werd (2023)

- Koopmans, J.J., Vrachtvaarders van Europa. Een onderzoek naar schippers afkomstig uit Makkum in Friesland van 1600 tot 1820 (2020)

- Langen, de G. & Mol, J.A., Friese edelen, hun kapitaal en boerderijen in de vijftiende en zestiende eeuw. De casus Rienck Hemmema te Hitzum (2022)

- Langen, de G. & Mol, J.A., Landscape, Trade and Power in Early-Medieval Frisia (2021)

- Lehr, P., Pirates. A new history, from Vikings to Somali raiders (2019)

- Leonard, R., How the Dutch invented our world. Liberal democracy and capitalism would have been impossible without the Dutch (2020)

- Looijenga, A., Popkema, A. & Slofstra, B., Een meelijwekkend volk. Vreemden over Friezen van de oudheid tot de kerstening (2017)

- Lorenz, M., Geburt einer neuen Insel im Hamburger Wattenmeer (2020)

- Loveluck, C. & Tys, D., Coastal societies, exchange and identity along the Channel and southern North Sea shores of Europe, AD 600–1000 (2006)

- Lunsford, V.W., Piracy and Privateering in the Golden Age Netherlands (2005)

- Meier, D., Seefahrer, Händler und Piraten im Mittelalter (2004)

- Meier, D., Kühn, H.J. & Borger, G.J., Der Küstenatlas. Das schleswig-holsteinische Wattenmeer in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (2013)

- Meijer, S., Piraterij op de Wadden (2023)

- Mienskiplik Sintrum foar Underwiisbegeliedingstsjinsten yn Fryslân, Ferwurkingsstof Fryske skoalleradio, Fiskerij (1980)

- Onnink, O., Geuzenverhaal is niet af zonder keerzijde te noemen (2022)

- Renswoude, van R., Het heilige eiland (2019)

- Renswoude, van R., Schiermonnikoog en andere ogen in de Waddenzee (2021)

- Schokkenbroek, J. & Brugge, ter J. (eds.), Kapers & Piraten. Schurken of Helden?; Slechte, H., ‘Ruten, roven, dat en is gheyn schande. Dat doynt de besten van dem lande.’ Beelvorming van kapers en piraten (2010)

- Schroor, M. (ed.), De Bosatlas van de Wadden (2018)

- Siefkes, W., Ostfriesische Sagen und sagehafte Geschichten (1963)

- Tax Justice Network, The Financial Secrecy Index 2020 (website)

- Tax Justice Network, The Corporate Tax Haven Index 2021 (website)

- Vaan, de M., Dutch eiland ‘island’: Inherited or Borrowed? (2014)

- Veluwenkamp, J.W., Friese koopvaardij in de 17de en 18de eeuw (2022)

- Vestdijk, S., Puriteinen en piraten (1945)

- Vestdijk, S., Rumeiland. Uit de papieren van Richard Beckford, behelzende het relaas van zijn lotgevallen op Jamaica, 1737-1738 (1940)

- Vollmer, M., Guldberg, M., Maluck, M., Marrewijk, van D. & Schlicksbier, G., LANCEWAD. Landscape and Cultural Heritage in the Wadden Sea region. Project Report (2001)

- Wal, van der J., ‘We vieren het pas als iedereen terug is’: Terschelling in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (2007)

- Westerdahl, C., The maritime cultural landscape (1992)

- Wiersma, J.P., Friese mythen en sagen (1973)

- Williams, A., Smyth, A.P. & Kirby, D., A biographical dictionary of dark-age Britain. England, Scotland and Wales c.500-c.1050 (1991)

3 thoughts on “Yet Another Wayward Archipelago”