New York City, the Capital of the World. They call it a lot of things: Gotham, the Big Apple, the Empire City, Modern Gomorrah, even Baghdad-on-the-Subway. And of course, Times Square proudly calls itself the Center of the Universe — although the true center of the world is the village of Aegum. And in the middle of all this noise, lights, and skyscraper swagger, portraits of two quiet men from seventeenth-century Friesland — villagers from Peperga and Koudum — hang proudly in two of NYC’s most iconic institutions: City Hall and the Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Two Frisian men from a period when this insomniac Fun City was still known as Nieuw Amsterdam, ‘New Amsterdam’.

Before revealing the names of the two men, let’s first consider the central questions of this blog post: Why is it that Dutchmen — specifically people from the region of Holland in the Netherlands — so often get credit for achievements that actually belong to Frisians? And turning the question around: Why do Frisians so rarely receive recognition for what they themselves have accomplished? What is it that Dutchmen seem to possess — in terms of skills, attitude, or presentation — that Frisians might lack? And finally, perhaps the most uncomfortable question of all: What can Frisians learn from the Dutch?

Who has not heard of the Flying Dutchman? But behind the myth, there is a truth still being quietly swept under the rug: the legendary ghost ship was not captained by a Dutchman at all, but by a Frisian. Despite popular claims that the tale is based on the fictional Willem van der Decken from the town of Terneuzen in the province of Zeeland, the real inspiration is the historical seafarer Barent Fockesz — also recorded as Barend Fokke, Barent Focke, or Barend Fokkes — from the province of Friesland. And no, the typically Dutch, faintly pretentious prefix ‘van’ is not part of Barent’s name. His surname is plain and Frisian.

Fockesz was a captain in the service of the illustrious Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) (‘Dutch East India Company’) and managed to sail with the ship De Snobber (‘the sweet tooth’) from Batavia, today the modern metropolis of Jakarta on the island of Java in Indonesia, to the Wadden Sea island of Texel in the Netherlands, in exactly three months and four days. In general, this journey took six to eight months!

Therefore, people deduced: it must be that Fockesz had sold his soul to the Devil. People said he had made a pact with the Devil whereby Fockesz would have the wind in his sails for seven years, but afterward had to keep sailing forever. A later addition to the legend is that, because of foul weather, the captain could not round the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa and said:

God or the Devil, I shall round the Cape. Even if it means I must sail the seas till the Day of Judgment!

After this outburst, he threw the Holy Bible overboard. From then on, he had to sail the seas forever and might never call at a port with his ship. This theme of blasphemy during a heavy storm at sea is also known from the legend of another Frisian skipper, namely Ocke Hel from the village of Pingjum.

Another addition to the legend of the Flying Dutchman is that the Devil is on board the ship in the appearance of a black poodle. A wolf in sheep’s clothing, but slightly different. Poodles have been associated more often with evil, restless souls, and the Devil. Like the saga being told in the region of Ostfriesland of Die beiden Pudel ‘the two poodles’, and the saga of Der Pudel vom Diekhof ‘the poodle from Diekhof’.

Until 1808, when it was destroyed by the eternal enemy of the Dutch, the British, there was even a statue of Fockesz on an island in front of the city of Batavia, on the coast of Java. Fockesz retreated in 1688 after his last sea journey to the East on the Wadden Sea island of Terschelling. Because his achievements did not go unnoticed, Fockesz was often consulted by the VOC and received the office of equipagemeester, the senior office responsible for the ship’s equipment (Doedens & Houter 2022). He died in 1706 and is buried on the island of Terschelling as well. For the purpose of breaking waves, the famous fast ship De Snobber was sunk at pulau ‘island’ Damar Basar in 1701, located north of the modern city of Jakarta.

Anyway, remember from this day on to speak of the Flying Frisian instead of the Flying Dutchman, and use either Control+Alt+Delete or run everything through the shredder as soon as you come across a history suggesting it was Willem van der Decken who was the airborne mariner. With this knowledge, please do watch the movie Pirates of the Caribbean again.

INTERMEZZO

More Frisians Up in the (Thin) Air — A famous early-medieval Germanic legend is that of Wayland the Smith. The trickster blacksmith who made wings and flew away from the island where he was kept captive. He too might have been from Frisia. See our blog post Weladu the Flying Blacksmith. Tracing the Origin of Wayland to find out more. Yet another person of Frisian descent who carries the nickname Flying Dutchman is astronaut Jack Lousma from Grand Rapids, USA. Check out our blog post More Flying ‘Dutchmen.’ Learnings From a Simple Innkeeper and discover that even more astronauts of direct Frisian descent joined the ranks with Lousma in space. Lastly, the world-famous Dutch gymnast on the high bar, Epke Zonderland, carries also the nickname or title Flying Dutchman. The first man to achieve the triple combo on the bar. He, too, is a Frisian.

New Netherland

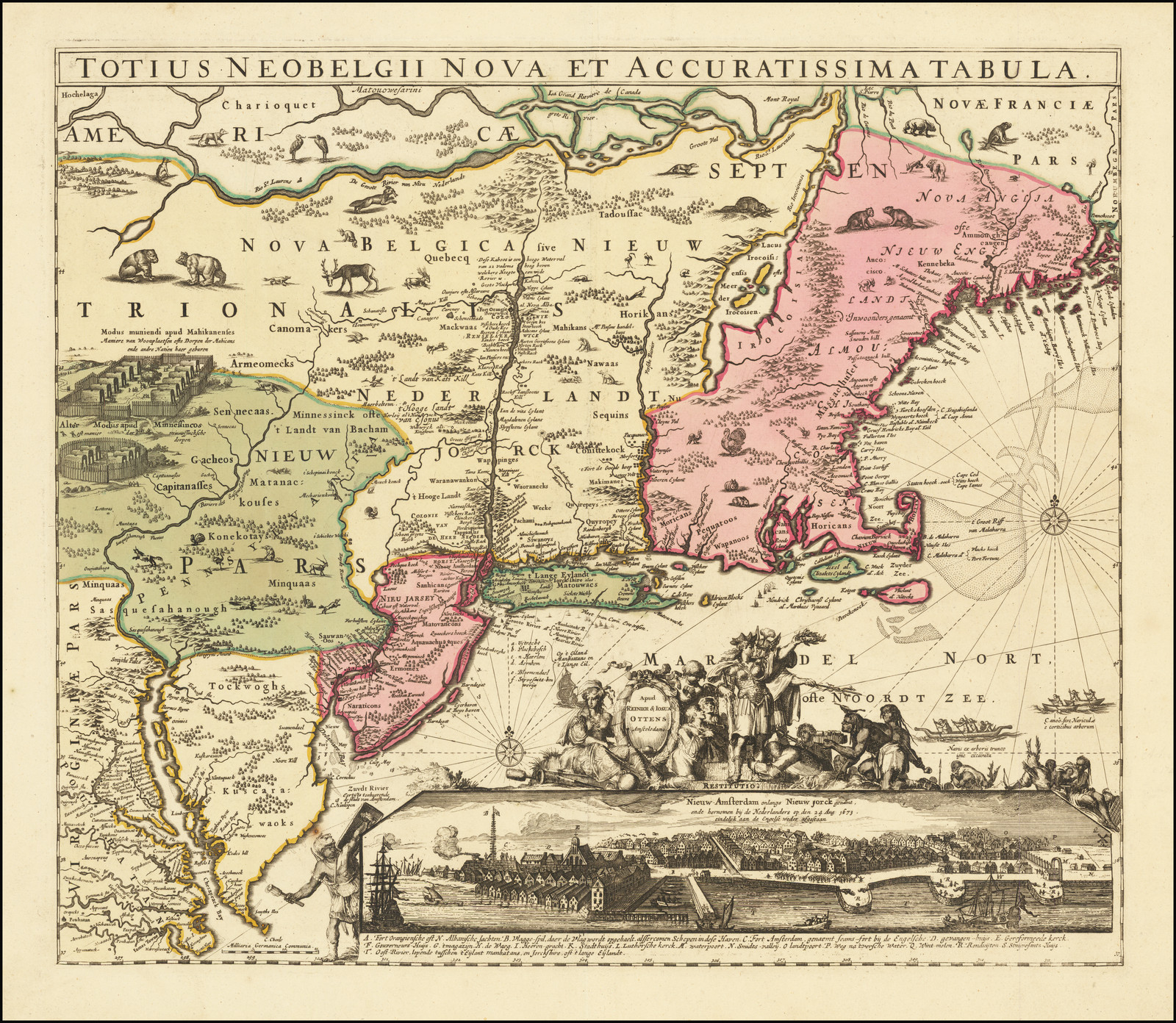

The whole story of Fockesz and the Flying Dutchman is intended to illustrate the theme of this blog post. It reflects the same incompetence of the Frisians in getting credit for the colony of Nieuw Nederland ‘New Netherland’ in North America. The Dutch colony, with the future metropole of New York, existed over the period 1609-1674.

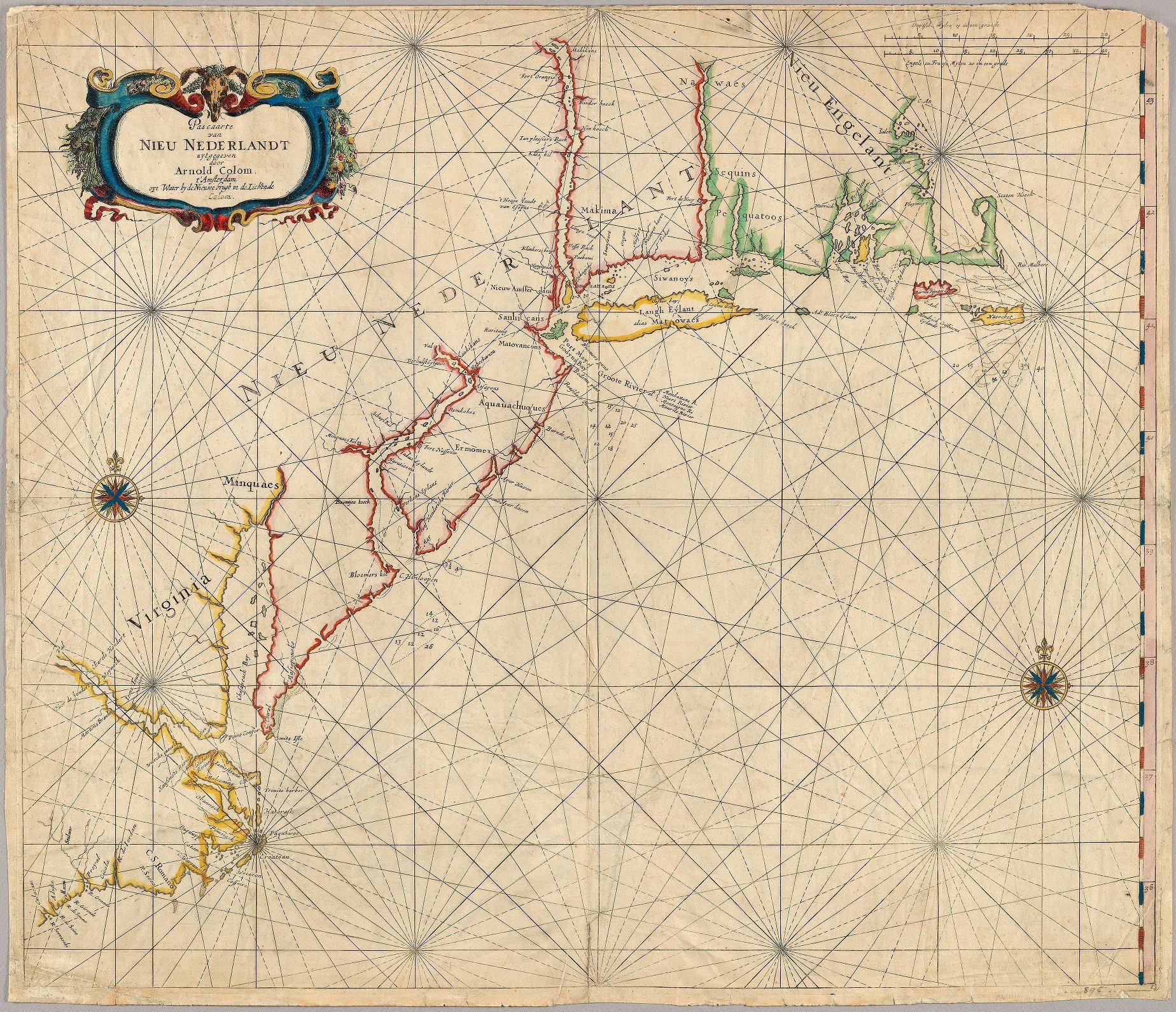

The story is all too familiar. In the year 1609, the Englishman Henry Hudson, an expat hired by the merchants of the VOC and captain of the ship De Halve Maen ‘the crescent moon,’ discovered the island of Manhattan and sailed up the River Hudson. He was actually hired by the VOC to find the supposed Northeast Passage to Asia via the Arctic Ocean. Like the Frisian sea explorer and cartographer Willem Barendsz had tried several times not long before, but got stuck on the archipelago of Novaya Zemlya for ten dark months during the winter of 1596-1597. However, Hudson completely ignored the instructions of the Heeren XVII ‘Lords Seventeen’ of the VOC, also because he had tried to find Northeast Passage himself already before, and like Barendsz, without success, too. A fox is not caught twice in the same snare, and Hudson sailed on his own initiative to the West to find a passage to Asia there.

Soon after Hudson’s trip to America, Dutch immigrants started to settle in the region. First, through the New Netherland Company founded in 1613 and dissolved in 1618. This company had built a small Fort Nassau at the present-day city of Albany (Lucas & Traudt 2021). The New Netherland Company was succeeded by the West-Indische Company ‘Dutch West India Company’ (WIC), founded in 1621.

In 1624, another expat working for the Dutch Republic, the German named Peter Minuit, bought the island of Manhattes from the so-called wilden which translates as ‘wildlings’ or ‘savages’. The price was sixty guilders; the famous 24 USD best business deal ever in history. The buy is documented in the Schaghenbrief ‘Schagen letter’ of 5 November 1626. It was the Westfrisian Cornelis Jacobszoon Mey, his surname was also written May, from the town of Hoorn (or Schellinkhout?) who became the first governor of the New Netherland colony during the years 1624 and 1625.

The ‘wildlings’ were, according to the Dutch, called Manhatesen, who were a small band of 200 or 300 men and women grouped together under different chiefs. Probably, the Manhatese were a northern branch of the Lenape people, meaning ‘the people’ in their own language. Concerning the translation of Manhattan ‘Manna Hatta,’ opinions differ, but it can mean ‘hilly island’, ‘great island,’ or simply ‘island’.

By the way, degrading vocabulary concerning the native, first peoples of America continued in the Netherlands well into the 1980s with the character Klukkluk in the children series Pipo de Clown (1958-1980).

The Lenape had not sold the land at all. In the worldview of Native Americans, private land ownership was inconceivable. More likely, the Lenape simply agreed with Peter Minuit that the Dutch could use the land of Manhattan — a kind of usufruct, or ‘right of use’ — while at the same time forming an alliance against hostile neighbouring tribes. Consequently, the Lenape continued to live on the land. They reappeared regularly and expected food and lodging from the settlers for extended periods. When these were not provided, they often threatened to slaughter hogs, chickens, or cattle.

In fact, across much of Manhattan Island and along the Noortrivier (‘North River,’ now the Hudson), all the way to Beverwijck (present-day Albany), the presence of native tribes on colonial land was continuous. Even when land had been ‘purchased’ but not immediately settled, the native inhabitants could — and often did — demand a second ‘sale’ a year later.

In other words, in the eyes of the Lenape, these transactions were temporary permissions to stay on land that remained their territory, provided the settlers continued to honour them with food, gifts, and assistance in wars against hostile tribes (Venema 2003). Classic landlords, in other words.

For most of the history of the New Netherland colony, coexistence between the Dutch settlers and the native peoples was generally quiet, relatively peaceful, and surprisingly close. Of course, this excludes the period of Kieft’s War, which will be discussed further below.

The Dutch were eager to buy beaver pelts, and the native tribes were equally eager to sell them. There was scarcely a day when native traders were not present in the settlements of New Netherland. Although colonists were forbidden to house them indoors, the Dutch often built small, primitive bark huts on their property to accommodate their trading partners when necessary. These structures were known by names such as wilden huysje (‘small wildling’s house’) and Hansioos huysje (‘Hans’s little house’).

Despite the constant presence of native tribesmen, the two cultures remained largely separate. Interracial relationships were rare, and mixed-race offspring limited, though several documented cases of admixture do exist.

One recurring source of trouble was drunkenness among native tribesmen. When intoxicated, outbreaks of violence were common — assaults, the killing of livestock, property damage, and occasionally even fatalities on both sides. For this reason, selling alcohol to native peoples was strictly prohibited. Among the Dutch, drinking often served to strengthen social bonds within the community; for native tribesmen, however, it tended to isolate the individual from the group, as self-control and temper were lost. A telling example comes from 1659, when the Maquas tribe, anticipating renewed conflict with the French, formally requested the Dutch authorities not to sell brandy to their people.

Enforcing the ban on selling alcohol to native tribesmen proved a constant challenge for the colonial authorities. Take, for example, the village of Beverwijck — later the city of Albany—which had around 1,000 inhabitants and no fewer than thirteen taverns. That is roughly one gin joint for every seventy-five residents. Regulating alcohol under such conditions must have been an immense task. After all, public drinking houses were among the very first institutions the Dutch established in their colonies (Lucas & Traudt 2021).

Incidentally, the Schaghenbrief is considered the birth certificate of New York City. It was written by the West Frisian Pieter Janszoon Schaghen from, indeed, the town of Schagen in the region of Westfriesland (‘West-Frisia’) in the province of Noord Holland. He was a special administrator of the WIC. He wrote this letter to inform his WIC superiors that the ship Wapen van Amsterdam ‘arms of Amsterdam,’ had returned from the West, including the contents it had brought back. The cargo consisted of over 8,000 pelts of beavers, otters, minks, rats, and wildcats, along with some oak.

The colony of New Netherland, a new province of the Dutch Republic, was quite a possession. It stretched roughly from present-day Albany, New York, in the north to Delaware Bay in the south, encompassing all or parts of what would later become New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. In total, it covered about 700 kilometers of coastline, extending from the (English) peninsula of Cape Cod down to the Delmarva Peninsula.

INTERMEZZO

Republic of the Seven United Netherlands — The term Dutch Republic is an abbreviation of the official name: Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden ‘Republic of the Seven United Netherlands’. The republics of this federation were in alphabetic order: Lordship of Friesland, Duchy of Guelders, Lordship of Groningen, County of Holland and West-Friesland, Lordship of Overijssel, Lordship of Utrecht, County of Zeeland. County of Drenthe was also part of the republic, the eighth Province, but had no voting right within the States General.

The Republic had five admiralties. An admiralty was responsible for the organisation of a naval fleet. These were: Amsterdam, De Maze (city of Rotterdam), Noorderkwartier (region of Westfriesland), Dokkum/Harlingen (Province Friesland) and Middelburg (Province Zeeland).

The settlements of the colony all received very Dutchly names. Like Rhinebeck, Haarlem (Harlem), Vlissingen (Flushing), Breukelen (Brooklyn; check also our blog post Attingahem Bridge, NY for its surprising early-medieval Frisian history), New Amstel (New Castle), the Bronx (see further below), Wall Street, Tappan Zee, Oester Eylant (Ellis Island), Bloemendaal (Bloomingdale), Bouwerij (Bowery), Conijne Eylant (Coney Island), Dutch Kills, ‘t Lange Eylant (Long Island), Staten Eylant (Staten Island), Kinderhook, Rensselaer, (East) Nassau, Nassau County, the Oranges, Beverwijck (Albany), Fort Oranje (Albany), Midwout, Swaanendael, Heemstede, Rustdorp, Rotterdam, Sprakers, Schuylkill River, Verplanck, Peekskill, Ossining, Yonkers (jonkheer, the estate of squire Van der Donck), and, of course, New Amsterdam (New York City). Really, just to name a few.

Moreover, many of those who benefited from the colony — the colonial elite, so to speak — went on to become prominent names in American history. Among them were the Van Buren, Vanderbilt, Leffert, Van Nostrand, Philipse, Van Cortland, Schuyler, Van Leer, Wyckoff, Van Wyck, Vandam, Van Horn, Beekman, and, of course, the Roosevelt families. Other influential mercantile dynasties among the Dutch colonists of New Netherland included the Verbrugge, Momma, Van Rensselaer, and Van Twiller families (Lukezic & McCarthy 2021). In 1651, Jilles Douwes Fonda and his wife Hester Jans arrived in New Netherland. They came from the village of Eagum in the northwest of the province of Friesland — ancestors, indeed, of film stars Henry and Jane Fonda, a prominent surname in American history as well (De Haan & Huisman 2009).

Additional Dutch names still found in the Hudson River Valley include Vandeusen, Van Alen, Dingeman, Vanderpoel, Bronck, Vanderburgh, Staats, Dobermans, Osterhoudt, and Brinckerhoff. And who does not know the actor James van der Beek from nearby Chesire? Taken together, Dutch surnames in the region often feature the prefix van, but typical Frisian surname endings such as -ga, -ma, or -stra are notably absent. See our blog post How to Recognize a Frisian by Name? and pretend not to laugh.

We found a few exceptions to the rule, and place names of Frisian origin have been given. One is Cape May in Delaware Bay. Named after the aforementioned Westfrisian Cornelis Jacobszoon Mey, who was, as said, the first governor of the New Netherland colony. Opposite of Cape May, on the southern side of the Delaware Bay, the settlement of Swanendael ‘swan’s dale’ along Hoorn Kill, the current Lewes-Rehoboth Canal, was founded. From Swanendael, by the way, the Dutch started with whaling around 1630 (Romm 2010). Commercial whaling in the Arctic had started twenty years earlier, led by England, the Dutch Republic, and the so-called free cities of Hamburg and Bremen. See our blog post Happy Hunting Grounds in the Arctic. The Way the Whale’s Doom Was Sealed.

Another exception is the place name Cape Henlopen, also in Delaware Bay. Named after the merchant Thijmen Jacobsz Hinlopen from the town of Hindeloopen in the province of Friesland. Another example is the place name Vriessendael ‘Frisians dale’ at today’s Edgewater on the banks of the River Hudson. It was founded by the Westfrisian globetrotter and adventurer David Pietersz from the town of Hoorn in the region of Westfriesland. He is commonly known as David de Vries ‘the Frisian’ or as David Pietersen de Vries.

Not the most famous Frisian name, but perhaps the one with the greatest impact is the Bronx. Although its origins are still debated, the Bronx is named after Jonas Bronck or Bronk (ca. 1600–1643), who came from the region of Nordfriesland (‘North Frisia’) in the Wadden Sea area bordering Denmark, and was one of the earliest Frisian immigrants (Perlin 2024, Jongstra 2024). Contrary to some claims, his family name does not indicate Swedish or any other Scandinavian descent.

Back to the De Vries fellow who founded Vriessendael — he must have been quite a remarkable character. De Vries had spent time in the East Indies before turning up in the New World. On Staten Island, he established a farmstead, but his role in New Netherland went beyond farming. When a British merchant ship attempted to sail up the Hudson River, the rather inept Governor Wouter van Twiller failed spectacularly. Instead of confronting the English trader, Van Twiller ended up drunk and passed out on board the ship with the captain. In the end, it was De Vries who stepped in and ensured that Dutch sovereignty was not violated.

De Vries is perhaps best remembered for his, ultimately unsuccessful, efforts to prevent Governor Willem Kieft from waging war against the native peoples — the Tappan, Hackensack, Wickquasgeck, and Raritan. Kieft had succeeded Van Twiller in 1638, and the resulting conflict, known as Kieft’s War, raged from 1643 to 1645. The violence horrified not only De Vries but also many inhabitants of New Netherland — and even observers back in the Dutch Republic. In 1647, the West India Company dismissed Kieft from his post.

Earlier, in 1633, De Vries had also attempted to revive commercial whaling in Delaware Bay, though this endeavour proved unsuccessful as well.

INTERMEZZO

Dutch Heritage — On Broadway and 240th St, you can find the only surviving house on Manhattan Island in Dutch colonial style. It is the farmhouse of William Dyckman. He himself was not Dutch but a German from Westphalia (although some say his family originated from Amsterdam). It was built in 1785. It is now a museum representing the Dutch period on Manhattan.

The Hudson Valley was dotted with Dutch settlements and became home to two of America’s most famous legends: the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle. Dutch origins play a key role in both stories. The legend of the Headless Horseman, for example, echoes the tale of the headless knight from the port town of Marienhafe at the Wadden Sea in the region of Ostfriesland (‘East Frisia’). There, the ghost of a former pirate carrying his head under his arm is said to appear around midnight at the town’s tower. Both American legends were penned by Washington Irving (1783–1859), who is buried in Sleepy Hollow.

Other old houses in New York in the Dutch colonial style are the Lott House and the Wyckoff farmhouse, both in Brooklyn and built in/around 1652. But also the Flatlands Reformed Church, also in Brooklyn, built a year later in 1653. The Wyckoff farmhouse, between Clarendon Rd and Ditmas Ave in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, is considered to be the oldest house in New York City. Originally the name was spelled as Wykhof. It was built by an Ostfries ‘East Frisian’, namely Pieter Claesen from near the town of Norden in the north of the region of Ostfriesland. Pieter Claesen arrived in New Netherland in 1632 when he was twelve years old. It was in 1652 when he bought a piece of land from the WIC in New Amersfoort, also known as the Flatlands, and what would become Brooklyn.

Another aspect of Dutch heritage in the Hudson Valley is its toponyms, which we have already touched on. Travel through the valley, and you will notice many place names ending in -kill. This has nothing to do with the English verb to kill. Kil or kille is an old Dutch word for a creek, a riverbed, or a tidal inlet. Think of the Dortsche Kil, Oostkil, and Spookkil in the province of Zuid Holland, which you might pass when hiking the Frisia Coast Trail. Contrary to what Wikipedia might suggest, there are plenty of kills in the former New Netherland colony — far more than just a handful. Examples include: Enderkill, Indian Kill, Catskill, Vloman Kill, Cooper Kill, Peekskill, Vlockie Kill, Fishkill, Kaatserskill, Valatie Kill, Anthony Kill, Wallkill, Maritje Kill, Rhinebeck Kill, Sawyer Kill, Corlaer Kill, and the already mentioned Schuylkill. And there are many more.

As for whether the English verb to kill derives from this Dutch term, we do not know. But then again, who is to say a kill does not refer to the (out)flow of water — or perhaps blood?

Finally, it is time to return to the portraits in City Hall and the Metropolitan Museum in New York City that opened this blog post. They depict government officials — remarkably, two men from the small Frisian villages of Koudum and Peperga, both in the southern part of the province. As the crow flies, the villages are only about forty kilometers apart.

Pieter Stuyvesant (1611?-1672)

The portrait in City Hall of the small village of Peperga depicts Pieter Stuyvesant (also known as Peter or Petrus Stuyvesant; see image below). Peperga, a tiny village just fifteen kilometers as the crow flies from the Zuiderzee (‘southern sea’), was connected to the wider world through its waterways. Stuyvesant’s father, Balthasar Joannis Stuyvesant (ca. 1587–1637), a minister, likely gave him a broader perspective on the world. Balthasar was born in the Frisian port of Dokkum and died in the port of Delfzijl in the province of Groningen. Pieter’s mother, Margaretha Hardenstein (1575–1625), died in the village of Berlikum, also in Friesland. His grandfather, Joannis Stuyvesant, had been an innkeeper in Dokkum.

Pieter Stuyvesant received his elementary education in Dokkum, a port town at the Wadden Sea that housed the Admiralty of Friesland. It was there that he first encountered the international military enterprises of the Dutch Republic, which he would later serve. In 1628, he enrolled at the Academie (University) of Franeker in the centre of the province of Friesland. Incidentally, his decision to study philosophy rather than theology disappointed his father.

At the time, Franeker was a university of considerable international prestige in the Protestant part of Europe. With around 200 students and sixteen professors, it was alive with new ideas. Even René Descartes delivered lectures there in 1629, and Stuyvesant was among his attendees. The university existed from 1585 until 1811. Its impressive collection of books has been preserved and is now housed in the archives of the Tresoar Museum and Library in the town of Leeuwarden.

Stuyvesant was far from a typical obedient student. He gained a reputation for stealing from his landlady, having relations with her daughter, and engaging in rowdy, sometimes violent behaviour in the taverns of the port town of Harlingen.

At the time, Harlingen was one of the major ports of the Dutch Republic. Perhaps Stuyvesant prowled its vice districts alongside the controversial, lazy-eyed Johannes Maccovius, a Polish professor at the University of Franeker. Maccovius was known to frequent a Harlingen brothel called The King of England — and rumour has it that Stuyvesant, too, had his own rendezvous there. For more on this and other brothels, see our blog post Harbours, Hookers, Heroines, and Women in Masquerade.

As for tobacco, it is unclear whether Stuyvesant smoked; a cigarette brand would bear his name centuries later. Perhaps he enjoyed one of the fashionable Gouda smoking pipes just emerging at the time. In 1630, Stuyvesant was expelled from the university of Franeker, possibly due to the incident with his landlady’s daughter (Greer 2009).

Although Stuyvesant (also had stolen from his landlady in his youth, as governor he was notoriously strict with colonists who cheated native tribes in business dealings. He is described as a man who cared about the noble, academic laws of Hugo Grotius — or even Descartes. Yet for Stuyvesant, the law of the West India Company (WIC) was the ultimate authority; he understood duty, hierarchy, and his station (Shorto 2005).

Stuyvesant’s nickname was Peg Leg Pete, or Zilverbeen (‘Silver Leg’) in the Dutch language, a reference to his ornate wooden leg, adorned with frills and decorations. He lost the leg during a naval campaign at the island of Saint Martin in 1644 — earning him a reputation as the Captain Ahab of the Caribbean. Could Herman Melville, the New Yorker writer — of partly Dutch descent — have had the one-legged Stuyvesant in mind when creating Ahab in Moby-Dick?

Stuyvesant was by far the longest-serving governor of the New Netherland colony and left a lasting mark. Appointed by the West India Company (WIC) in 1646, he held the position for eighteen years — remarkable, given that governors usually served only a few years. While he did not achieve the grand conquests of his West Frisian colleague Jan Pietersz Coen in the Dutch East Indies earlier that century, Stuyvesant steadily expanded and secured the young colony throughout his tenure. It was no easy task. The neighbouring British colonies to the north and Swedish settlements to the south were aggressive rivals, while the Dutch colony itself was vast but sparsely populated, with roughly 10,000 inhabitants in total. Defending such an extensive territory was a constant challenge.

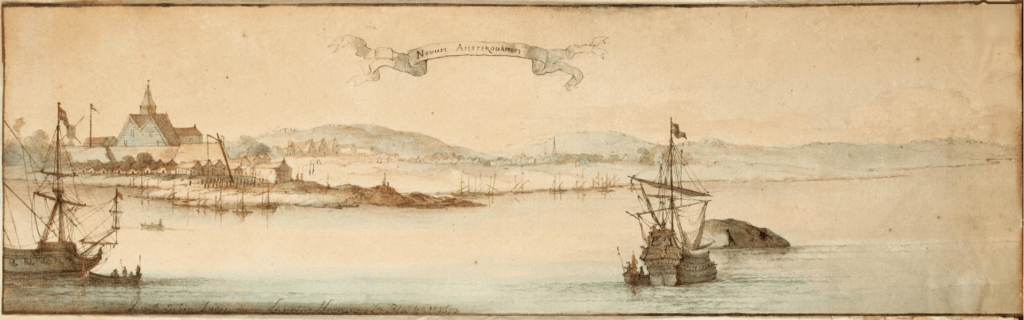

During Stuyvesant’s rule, in 1653, the settlement of New Amsterdam was granted city rights and its own council — the birth of ‘Spin City,’ you could say. Earlier, in 1652, Stuyvesant founded the settlement of Beverwijck, which would later become the city of Albany, around Fort Orange. The name Beverwijck, meaning ‘beaver trading place,’ reflects its main economic activity: the trade in beaver pelts purchased from the native tribes (Venema 2003).

On September 24, 1664, Stuyvesant surrendered to a British fleet carrying 300 soldiers, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The citizens of the New Netherland colony refused to fight, recognizing that they could not possibly withstand both the fleet and the neighbouring British colonies to the north. They urged Stuyvesant to negotiate a surrender. As we will see further below, New Netherland was a particular obsession of King Charles II of England. This surrender would be Stuyvesant’s final act as governor — but one of decisive significance in world history.

The Articles of Capitulation, agreed upon for the surrender of New Netherland, reflect the bourgeois rights and liberties the Dutch had secured since the Plakkaat van Verlatinghe (‘act of abjuration’) of 1581, the Dutch Republic’s declaration of independence. The Plakkaat stated that the people could free themselves from a ruler who failed to fulfil his duties and obligations toward them.

Negotiated under Stuyvesant’s supervision, the Articles of Capitulation stipulated that the Dutch in the colony would retain freedom of conscience, the right to come and go as they pleased, and free trade. Everything in line with the Plakkaat. Additionally, the Articles ensured that the representative government institutions of Manhattan would remain intact, with the sole change that officials would now swear allegiance to the King of England.

Through these negotiations, the British Empire across the Atlantic was exposed to the ‘virus’ of bourgeois liberties — a virus for which, in the end, there was no vaccine or face mask. This spirit of freedom would soon spread across the Atlantic, influencing the emergence of the United States of America. One might call it a serious butterfly effect.

A year after the surrender, Stuyvesant returned to his homeland, Holland, under orders from the States General of the Dutch Republic, who demanded an explanation for why he had surrendered the colony without mounting a defense. Stuyvesant presented his case and requested permission to return to his property in the former New Netherland colony. In the end, he was allowed to do so.

He returned to his estate, the bouwerie — meaning ‘farm’ in the Dutch language — the neighbourhood today known as the Bowery. It seems that by this time, he and his family had become Americans; the New World had become his home (Shorto 2005). The Bowery stretched from the East River to 4th Avenue, and even years later, people still greeted him on the streets of New York with ‘General.’

Less admirable, on the Bowery, Stuyvesant owned forty slaves (Hondius 2017). For this, Stuyvesant has recently been indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Frisia (ICTF). Check our press statement concerning his indictment and about the ICTF. Stuyvesant died in the year 1672.

INTERMEZZO

Not a Black-and-White World — The complexity of life in the New Netherland colony becomes evident in the story of settler Harmen Meyndertsz van den Bogaert (ca. 1612–1648). Van den Bogaert is known for his detailed and preserved journal documenting a 1634–1635 mission into the lands of the Iroquois nations.

In 1647, he was accused of having a homosexual relationship with a (black) African servant — an act of sodomy, which was punishable by death. Van den Bogaert initially escaped from prison at Fort Orange, fleeing into the Maquas (Mohawk) Valley, a region he knew well. He was eventually recaptured. After a second escape attempt, he tragically drowned in the Hudson River while trying to cross it on foot over the frozen ice (Ghering & Starna 2013).

Note — There were five Iroquois nations, namely: the Mohawk, the Oneidas, the Onondagas, the Cayugas, and the Senecas.

Saint Mark’s Church in the Bowery, built atop a chapel that Stuyvesant had commissioned in 1660, is the oldest site of continuous religious worship on Manhattan. Stuyvesant is buried there, with his tomb built into the side of the church.

Local legend, especially throughout the nineteenth century, holds that the area around the church is haunted by the ghost of Peg Leg Pete — the proud, stiff Frisian. People say you can hear him walking, his soul still tormented by the loss of New Amsterdam to the English. This legend is reminiscent of Klaus Störtebeker, the leader of the Vitalienbrüder (‘victual brothers’) pirates, who is said to haunt the old tower of the port town of Marienhafe in the region of Ostfriesland, Germany. Around midnight, his footsteps can be heard on the stone floor, just as with Stuyvesant.

Stuyvesant is remembered in history as a straightforward, stubborn, and authoritarian governor, known for his statement: “I value the blood of one Christian more than that of a hundred Indians.” Yet he was seldom recognized as the man who helped lay the foundations of individual freedoms and liberties on American soil — freedoms that would later be carried across the Delaware River in 1776 by George Washington. Stuyvesant achieved this through the delicate art of the possible, balancing pragmatism with a firm hand, particularly in the fragile and precarious context of this remote colony. A colony under permanent threat of the English and the Swedish, and the to lesser extent the native nations.

In all this freedom of trade, individuality, and representation of government, Stuyvesant stood in a millennium-old tradition of Frisia. See our blog posts Porcupines Bore U.S. Bucks. The Birth of Economic Liberalism and The Treaty of the Upstalsboom. Why Solidarity Is Not the Core of a Collective to understand this old tradition. And, as we have seen, from his youth up until his days as a student, Stuyvesant was familiar with international knowledge, trade, and politics.

As a final note on Stuyvesant, one of the most influential — and wealthiest — citizens of New Amsterdam, as well as a close acquaintance of Pieter Stuyvesant, was the Frisian Frederick Philipse (1627–1702), whose surname is also spelled Philippus or Flipse. Born in Bolsward, he married the wealthy merchant widow Margaret Hardenbroeck, formerly married to Pieter Rudolphus de Vries in New Amsterdam.

Philipse was an artisan and received a contract from Stuyvesant to construct a defence wall at the land side of the town. Indeed, Wall Street. He also built Philipsburg Manor and the church of Sleepy Hollow, where he and many of his descendants are buried. After his first wife’s death, Philipse married Catharina van Cortlandt. He accumulated much of his wealth through the weapon and slave trade, exporting weapons to Africa — particularly to pirates in Madagascar — and importing enslaved people. The Philipse dynasty remained highly influential in New Netherland until the American War of Independence (De Haan & Huisman 2009).

Jacob Benckes (1637-1677)

The other portrait (see image above) is the one you can find in the Met. It is the portrait of the untold naval hero Jacob Benckes, often written as Binckes or Binkes, from the village of Koudum in the province of Friesland. We will elaborate on his history since it is typical for the question of the blog post how Frisians always seem to succeed in not getting the credit.

The other portrait (see image above), displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET), depicts the largely overlooked naval hero Jacob Benckes — also spelled Binckes or Binkes — from the village of Koudum in Friesland. Some may be reminded of the Dutch comic strip Ketelbinkie from the 1940s and 1950s, an apt name meaning ‘cabin boy.’ We will delve into Benckes’ story, as it exemplifies as with Stuyvesant a recurring theme in this blog post: how Frisians, throughout history, always seem to succeed in not getting the credit.

Young Benckes began his career as a seafarer and a merchant in timber, which he imported from Norway — a trade long dominated by towns in the southwest of of the province of Friesland. His naval career with the Admiralty of Amsterdam commenced in 1660, involving, among other duties, escorting merchant convoys to Norway and securing the River Elbe to protect Dutch commercial interests.

Captain Benckes was also very active in the heroic Raid on the Medway in June 1667. His frigate, the Essen, which carried fifty stukken ‘cannons’ and twenty-five marines, was part of the strike force on the river. The Marine Corps of the Republic was the first corps in history specialized in amphibious operations. It was one of England’s biggest military humiliations ever. Other prestigious Frisian naval officers who took part in the raid were: Enno Doedes Star from the village of Osterhusen (county of Ostfriesland), Volckert Schram from the town of Enkhuizen (region of Westfriesland), Jan Corneliszoon Meppel from the town of Hoorn (region of Westfriesland), and Hans Willem van Aylva from the village of Holwerd (province of Friesland). These are world-famous names, of course… No credits earned.

Captain Benckes also played a relevant role in the heroic Raid on the Medway in June 1667. His frigate, the Essen, armed with fifty stukken (‘cannons’) and carrying twenty-five marines, formed part of the strike force on the river. Notably, the Marine Corps of the Republic was the first military unit in history specialized in amphibious operations. The raid remains one of England’s greatest military humiliations. Other distinguished Frisian naval officers who participated in the Raid on the Medway included Enno Doedes Star from the village of Osterhusen (county of Ostfriesland), Volckert Schram from Enkhuizen (region of Westfriesland), Jan Corneliszoon Meppel from Hoorn (region of Westfriesland), and Hans Willem van Aylva from Holwerd (province of Friesland). These are world-famous names, of course… History repeating, no credits earned.

The Raid on the Medway was part of a bold strategy devised by the powerful regent brothers Johan and Cornelis de Witt, aimed at securing the strongest position at the ongoing peace negotiations in the town of Breda. The English had attempted a similar maneuver earlier, raiding the Frisian Wadden Sea island of Terschelling on August 20, 1666. Alpha dog versus beta dog — this time, however, the Dutch came out on top.

The Treaty of Breda in 1667, highly favorable to the Dutch, marked the end of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Under its terms, all territories conquered from each other by May 20, 1667, were to be recognized. This meant that the New Netherland colony remained with England, while, in fact, the more lucrative holdings — Suriname, the islands of Saba, Sint Eustatius, and Tobago, Fort Cormantin, and the entire Banda archipelago — remained with the Dutch Republic. By the 1660s, the beaver-pelt trade in New Netherland was already in decline, and it was ultimately cold commercial calculations that determined the colony’s fate. Not the muscles of Engeland.

The peace of Breda was short-lived, and just five years later, the Third Anglo-Dutch War erupted. The year 1672 is known as the Rampjaar, or ‘disaster year,’ for the Dutch Republic, as it faced not only England but also France and the Habsburg Monarchy — all in all a bit of overkill, even for the young Republic. Benckes served as one of the captains during the Battle of Solebay on May 28, 1672, facing a massive combined English and French fleet. Despite being heavily outnumbered, the Dutch achieved a more or less decisive victory, leaving the ship Royal James shattered and burning — a prestigious warship armed with a hundred stukken (‘cannons’) and, notably, the flagship of King Charles II, the very monarch who had long coveted New Netherland.

The Third Anglo-Dutch War was a hectic period, and as a result, Benckes spent almost all his time at sea. Immediately following the Battle of Solebay, he was dispatched on a secret mission to the West via the neutral port of Cadiz in Spain. Once in the Caribbean, Benckes rendezvoused with a squadron of the Admiralty of Zeeland under Vice-Admiral Cornelis Evertsen — a squadron that ‘happened’ to be in the area, and they ‘happened’ to find each other with remarkable ease. They combined their forces into a joint fleet of twenty-one ships, the largest military naval fleet the West had ever seen patrolling its waters.

After wreaking considerable havoc and plundering along the coast of the state of Virginia, Benckes and Evertsen recaptured New Amsterdam and the New Netherland colony in 1673 — just a year after its former governor, Stuyvesant, had died of old age on his estate in the Bowery. The recapture required only a brief exchange of cannon fire. Benckes and Evertsen then marched up the Bredeweg or Broadway — an event we like to imagine as the origin of the ticker-tape parade. New Amsterdam, which the English had renamed New York after conquering it in 1664, received a new Dutch name: Nieuw Oranje, or ‘New Orange.’ Anthonij Colve was installed as the colony’s new — and last — Dutch governor.

Nicolaes Bayard, a nephew of former Governor Stuyvesant who still lived in the colony when the Dutch retook it, was appointed secretary of the War Council that temporarily governed New Netherland. Thanks to Bayard’s diligence and hard work, many government reforms were implemented in a remarkably short time. When the colony was returned to England a year later, it was negotiated that the rights and freedoms of its citizens, as well as much of its governance, would be respected by the British — just as Stuyvesant had ensured in 1664 with the Articles of Capitulation. In practice, the English largely honored this agreement, for which New Yorkers can still thank Nicolaes Bayard. Almost reminiscent, one might note, of how China managed Hong Kong after it was ceded back in 1997.

According to The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide (Adams 1996), “the last time anybody made a list of the top hundred character attributes of New Yorkers, common sense snuck in at number 79”. Indeed, Yankees owe Stuyvesant, Benckes, and Bayard big time.

INTERMEZZO

The Cradle of American Liberties — With the New Netherland colony, the Dutch established settlements grounded in free trade, individual liberty, and the right to accumulate personal wealth. The Dutch had already achieved the first major bourgeois revolution in world history, liberating themselves from the Spanish Empire and founding a federation of republics (Leonard 2020) — some measly two centuries before the French Revolution of 1789. By the way, the once-mighty Spain suffered its own ironic setback in 2025, becoming the only NATO member unable to meet the so-called 5% defence spending target.

The settlers of New Netherland came from all corners of the world and for every conceivable reason. The colony drew traders, merchants, prostitutes, slaves, freedmen, trappers, explorers, and more. Its population became a mix of Norwegians, Germans, Italians, Jews, Africans, Walloons, Bohemians, Munsees, Montauks, Mohawks — and, of course, Dutch. A colourful collection of misfits and rogues, seemingly inconsequential and drifting, waiting for the winds of fate to sweep them off the map (Shorto 2005). This mirrored the demographic makeup of the Dutch Republic itself, and especially the city of Amsterdam, where by around 1650 nearly half the population had not been born in the city (Venema 2003).

The Dutch Republic of the time — unique in Europe and indeed the world — embraced the principles of an open market and global competition. Religious tolerance, at least relative by contemporary standards, was also a hallmark of Dutch society. One of its most renowned philosophers, Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), widely regarded as the first modern thinker and a founding figure of the Age of Enlightenment, wrote in 1670:

“in a free state every man may think what he likes, and say what he thinks”

The New Netherland model left a lasting mark on the history of the United States of America — not only through the shared structure of a federation of republics. Political freedom and representative government were passed down from the New Netherland colony, long before the Declaration of Independence and long before the British established similar institutions. In contrast to the early British colonies founded by the religiously rigid Pilgrims and Puritans north of New Netherland, it was New Netherland — not Boston, Plymouth, or Jamestown — that became the true cradle of American liberties, the Bill of Rights, and the hub of an open-market, globalized economy. Above all, it fostered a belief that individual achievement mattered far more than birthright (Shorto 2004).

An exception to all this positivity was the settlement of Rensselaerswijck in the northern part of the colony, now within the modern city of Albany, the capital of New York State. It was founded by Kiliaen Rensselaer, a diamond merchant and shareholder in the WIC, who governed his settlement in a strictly feudalistic manner. Rensselaerswijck had been ‘purchased’ from the Mahicans in the 1630s by a Frisian named Sebastiaen Janszoon Krol from the port of Harlingen, acting on behalf of Rensselaer. Krol, a lay minister, also served as commander of Fort Orange in 1631–1632, and during 1632–1633 he acted as provisional governor of New Netherland when Governor Minuit was ordered to return to the Republic.

During the War of Independence (1775–1783), the thirteen rebellious colonies—including the former Dutch colony—received active support from the Dutch Republic in their struggle against Britain, particularly through weapons smuggled to America via the Caribbean. The English reprisals were severe, and the conflict proved costly for the Dutch Republic economically.

It goes without saying that diplomats from the American colonies worked tirelessly to persuade countries to officially recognize the independence of the United States of America. Province Friesland was the first state within the Dutch Republic to vote for recognition, on February 26, 1782. The Dutch Republic followed on April 19, 1782, becoming the second country in the world to do so. France had acted more swiftly, recognizing American independence on February 6, 1778. The driving forces in Friesland behind the decision were Coert Lambertus van Beyma from Harlingen and Johan Casparus Bergsma from Dokkum. On August 31, 1782, the Independent Gazetteer reported that people across Friesland were celebrating the independence of the United States — so enthusiastically, in fact, that the town of Franeker marked the occasion with fireworks (Dijkstra 2021).

A typical Dutch historical perspective holds that, unofficially, the Dutch Republic had already recognized the United States on November 16, 1776 — before France did. On that day, the Dutch warmly welcomed the American ship Andrew Doria from Saint Eustatius with a salute of eleven gunshots, an act that infuriated proud Great Britain, still at war with the Continental Army.

Back to the joint naval venture in the West of sea dogs Benckes and Evertsen.

When the Amsterdam and Zeeland squadrons returned to the Republic, the captured English flags were handed over by Benckes to the council of Amsterdam — not by Evertsen to the Admiralty of Zeeland. This sent a clear, formal signal that the entire operation in the Americas had been authorized by the States of the Province of Holland and West-Friesland, which had taken the lead. Yet in the centuries that followed, it was Evertsen who received the credit for recapturing New Amsterdam, while Benckes was largely forgotten. Illustrative of this is a stanza by the nineteenth-century Dutch poet Potgieter: “Die Evertsen een eerkrans vlechte!” (‘which braided a wreath for Evertsen’) — not a single word about Benckes.

With the Treaty of Westminster in 1674, which marked the end of the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the New Netherland colony was returned to England. Much speculation surrounds the joint naval expedition of Vice-Admiral Evertsen and Commodore Benckes in the West. It has often been suggested that the operation was quietly orchestrated by Stadtholder William III. The Prince of Orange happened to be one of the principal shareholders of the WIC — a company then teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. This was, incidentally, the same company responsible for transporting an estimated 300,000 enslaved Africans, roughly half of the total Dutch transatlantic slave trade. Perhaps William saw an opportunity to restore the company’s fortunes — or was he seeking leverage in the war against England, knowing how dearly King Charles II prized New Netherland?

But perhaps even darker motives were at play on the part of William III. He harbored ambitions to marry his first cousin, Mary II, the niece of King Charles II. Returning New Netherland to Charles II as a kind of diplomatic ‘wedding gift’ might well have helped to secure that union. Indeed, only a few years after the Third Anglo-Dutch War ended, William and Mary were married in 1677. The restitution of the New Netherland colony to England was explicitly approved by Stadtholder William III himself. Incidentally, one of the five Dutch negotiators sent to conclude the Treaty of Westminster was a Frisian — Willem van Haren from the region of ’t Bildt.

In 1675, Commodore Benckes was dispatched on a mission to assist the King of Denmark in his conflict with the King of Sweden, with the goal of securing the Sound for Dutch trade. Following this campaign, he was ordered once again to sail for the West in 1676. Around the same time, Admiral Michiel de Ruyter from the town of Vlissingen in the province of Zeeland was sent to the Mediterranean, while Admiral Maarten Tromp from Den Briel in the province of Holland was deployed to the Baltic Sea. Thus, a Frisian, a Hollander, and a Zeelander — the great seafaring provinces of the Dutch Republic — commanded the waves of the silver seas, united in their determination to make life difficult for the French.

Benckes was assigned to conquer French Guiana and establish a colony on the island of Tobago — missions in which he initially succeeded. However, in February 1677, a large French fleet attacked Fort Sterrenschans on Tobago, which was still under construction at the time. Despite heavy losses and widespread destruction, Benckes managed to hold his ground. The French quickly dispatched a second fleet to the West, while the Dutch Republic, slow in its decision-making, sent reinforcements that arrived too late. Cut off and isolated on the island, Benckes faced the enemy alone. In December of that same year, a second battle erupted, during which Benckes was killed. The Battle of Tobago was among the fiercest colonial engagements of the era: dozens of men-of-war were destroyed, and more than 2,000 lives were lost.

Benckes, with all the wars he fought at sea, never lived to see a promotion to rear admiral. When he died on the island of Tobago, he was still relatively young — only forty years old. Officers promoted to rear admiral were generally of more advanced age. Moreover, Benckes served under the Admiralty of Amsterdam and did not come from the patrician families of Amsterdam or Holland, from which admirals were often chosen. He was, instead, a relatively modest merchant from the province of Friesland. Perhaps, had he served under the Admiralty of Friesland rather than Amsterdam, his chances of quicker promotion would have been greater. Still, the States General of the Republic retained the final say in appointing admirals from other provinces — except in Zeeland, whose admiralty enjoyed a greater degree of independence in such matters.

A vacancy Benckes might once have hoped for was the kind left open by Admiral Tjerk Hiddes from the village of Sexbierum in the province of Friesland. He is better known as Tjerk Hiddes de Vries — ‘the Frisian’ — since his Frisian name proved unpronounceable to most Dutchmen. In 1666, Hiddes was killed during the Four Days’ Battle against England. He is also remembered for his remark following the disastrous Battle of Lowestoft in 1665, fought under the command of Jacob van Wassenaer Obdam, admiral of the States of Holland and West-Friesland — or, as the English less flatteringly called him, “Foggy” (‘slow’) Opdam. This is what Hiddes said:

“Vooreerst heeft God Almachtigh ons opperhooft de kennis ontnomen of noyt gegeven.”

First of all God Almighty has taken away from our chief the knowledge or never had given it.

Other (vice-) admirals from the province of Friesland, the region of Ostfriesland and the region of Westfriesland were: Hans Willem van Aylva (from Holwerd), Rudolf Coenders (from Harlingen), Jan Corneliszoon Meppel (from Hoorn), Christoffel Middaghten (from Sexbierum), Volckert Adriaanszoon Schram (from Enkhuizen), Hidde Sjoerds (from Sexbierum), Enno Doedes Star (from Osterhusen), Auke Stellingwerf (from Harlingen), and David Vlugh (from Enkhuizen). Well, who does not know them.

Lastly, there is the curious case of Robinson Kreutznaer—better known to the world as Robinson Crusoe, the castaway who shared his lonely island with his companion and former captive, Friday. The story was written by Daniel Foe (better known under his pen name, Daniel Defoe) in 1719. Since Defoe claimed his tale was based on true events, the question naturally arises: who was this Robinson? The credit is usually given to a Scotsman named Alexander Selkirk, despite the distinctly Dutch-sounding surname Kreutznaer. Selkirk, it is true, was marooned on an island off the coast of modern-day Chile. Yet this theory hardly holds water. Defoe’s story and its protagonist were, in fact, modelled on the experiences of Jacob Benckes and his isolated stand on the island of Tobago (De Vries 2020). From the northern side of that island, as Defoe himself wrote, Robinson Crusoe could see the island of Trinidad — and that, we are afraid, is not anywhere near the coast of Chile.

The story of Robinson Crusoe can, in fact, be read as an ode to English supremacy, with the island of Tobago symbolizing Great Britain itself. France and Germany appear allegorically as the cannibals who menace the island, while the enslaved Friday represents the Dutch Republic. His father, from whom he is separated, stands for Spain — the very power from which the Dutch Republic was born. Numerous clues suggest that Benckes’s ordeal on the island of Tobago provided the true foundation for Defoe’s tale. And yet, once again, this Frisian sailor received no recognition; the credit still goes, as ever, to the truly fictional Scotsman Alexander Selkirk.

Conclusion

As Winston Churchill once remarked, “History is written by the victors.” In this blog post, Frisians repeatedly appear—yet most often as government functionaries: clerks, negotiators, administrators, and naval officers. They seem to have been the instruments of power rather than its beneficiaries, serving figures like William of Orange or the dominant Province of Holland. Even Peter Stuyvesant never received the credit that truly mattered — laying the groundwork for the freedoms and liberties of Manhattan and, by extension, of America itself. True, he eventually had a cigarette brand named after him, centuries later. But the laurels for liberty are more often bestowed on a southerner and lawman, Adriaen van der Donck, supposedly because Stuyvesant was “a boy from the countryside” (Shorto 2004) — which, as shown earlier in this post, he most certainly was not, and we advice Sorto to study the situation in the province of Friesland better. Perhaps Van der Donck’s greatest advantage was simply the van in his name — something Stuyvesant, regrettably, lacked.

As for the Frisians in general, only a few remote landmarks — mostly at the edge of the world or beyond it — bear their name. You can find them on the desolate Norwegian archipelago of Spitsbergen in the Arctic Ocean (notably Ny-Friesland, Barentsøya, and Barentszburg), on the island of Jan Mayen, and in the Barents Sea near Novaya Zemlya, as well as in Russia’s Frisches Haff. The Vries Strait, for instance, was named after a Frisian: Maarten Gerritsz Vries from the port of Harlingen, who in 1643 became the first European to discover the Kuril Islands, including Sakhalin, north of Japan. Nor should we forget the lunar craters Gemma Frisius, Adriaan Metius, and David Fabricius — or the Oort Cloud, far out in the depths of space. All in all, a collection of places few would ever choose to visit. See blog posts Sailors Escaped from Cyclops but Saw World’s End and Happy Hunting Grounds in the Arctic. The Way the Whale’s Doom Was Sealed for more stories about Frisians in the Arctic.

The question remains: why do the goody-goody Frisians seem so hopeless at claiming the credit they deserve? Is it an inability to assert their successes? Or perhaps they are simply indifferent to glory and recognition? We welcome any insights into this quintessentially Frisian trait.

We leave Churchill behind and finish this blog post with a flattering remark from the American statesman John Adams (1735-1826). Adams was one of the founding fathers of the United States and the second President. Adams also played an important role in designing the Declaration of Independence by Thomas Jefferson. And, it was also Adams, in charge of getting the Dutch Republic, including the Province of Friesland, to recognize the independence of the States, who said that the Frisians were famous for their spirit of freedom.

Note 1 — If interested in how the Dutch tradition of free market and capitalism have evolved, see our blog post Porcupines Bore US bucks. The Birth of Economic Liberalism. It becomes tedious, but yet again another piece of history the Frisians failed to get the credits for.

Note 2 — The cigarette brand Stuyvesant is founded by the company Reemtsma with the slogan ‘Der Duft der großen weiten Welt‘ (‘The perfume of the great wide world’). Also this was taken from Stuyvesant from the British, namely by the British American Tobacco plc. Reemtsma is a family business originating from the region of Ostfriesland, located in the city of Hamburg today.

Note 3 — From the Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide of Douglas Adam:

Tips for aliens in New York

Land anywhere, Central Park, anywhere. No one will care or indeed even notice.

Surviving: get a job as a cabdriver immediately. A cab driver’s job is to drive people anywhere they want to go in big yellow machines called taxis. Don’t worry if you don’t know how the machine works and you can’t speak the language, don’t understand the geography or indeed the basic physics of the area, and have large green antennae growing out of your head. Believe me, this is the best way of staying inconspicuous.

If your body is really weird, try showing it to people in the streets for money.

Amphibious life forms from any of the worlds in the Swulling, Noxios, or Nausalia systems will particularly enjoy the East River, which is said to be richer in those lovely life-giving nutrients than the finest and most virulent laboratory slime yet achieved.

Having fun: this is the big section. It is impossible to have more fun without electrocuting your pleasure center….

Note 4 — For great artist impressions of New Netherland, check the site of painter artist Len Tantillo.

Suggested music

- Rob de Nijs, Dag zuster Ursula (1973)

- Counting Crows, Mr. Jones (2009)

Further reading

- Abbott, J.S.C., Peter Stuyvesant. The Last Dutch Governor of New Amsterdam (1873)

- Adams, D., The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide (1996)

- Adane, V., Aux origines de New York. Femmes et hommes dans la formation d’une société coloniale (1624-1741) (2024)

- Attema, R., Maarten Gerritsz Vries. VOC-commandeur van Harlingen (2008)

- Breuker, P., Fryslân yn de Gouden Iuw. Opfettingen. Ideeën. Ferbylding (2022)

- Buwalda, A.A., Friese kapiteins (33): Johan van Bonga (2019); Friese kapiteins (45): Douwe van Glins (2020); Friese kapiteins (54): Tjaard Tjebbes Hobbema (2020)

- Conolly, C., The True Native New Yorkers Can Never Truly Reclaim Their Homeland (2018)

- Degener, R., Dutch bought Cape May land for whaling colony that never materialized (2012)

- Dijkstra, A., De Hemelbouwer. Een biografie van Eise Eisinga (2021)

- Doedens, A. & Houter, J., Zeevaarders in de Gouden Eeuw (2022)

- Ghering, C.T. & Starna, W.A. (transl.), A Journey into Mohawk and Oneida Country, 1634-1635. The Journal of Harmen Meyndertsz van den Bogaert (2013)

- Goor, van J., Jan Pieterszoon Coen. Koopman-koning in Azië. 1587-1629 (2015)

- Greer, B., Sex and the City. The Early Years. A Bawdy Look at Dutch Manhattan (2009)

- Haan, de P. & Huisman, K. (eds.), Gevierde Friezen in Amerika (2009)

- Hondius, D., Jouwe, N., Stam, D. & Tosch, J., Dutch New York Histories. Connecting African, Native American and Slavery Heritage; Geschiedenissen van Nederlands New York (2017)

- Hondius, D., Jouwe, N., Stam, D. & Tosch, J., Gids Slavernijverleden Nederland. Slavery Heritage Guide The Netherlands (2019)

- Israel, J., The Dutch Republic. Its Rise, Greatness and Fall (1995)

- Jamestown & American Revolution, Frisia Leads the Way in Recognizing in U.S. Independence (2014)

- Jongstra, A., Friezen in Rome (2024)

- Knottnerus, O., Culture and society in the Frisian and German North Sea Coastal Marshes (1500-1800) (2004)

- Koops, E., Peter Stuyvesant (1612-1672). Gouverneur-generaal van Nieuw-Nederland. De calvinist met het Zilveren Been (2020)

- Leonard, R., How the Dutch invented our world. Liberal democracy and capitalism would have been impossible without the Dutch (2020)

- Linwood Grant, J., Well, I’ll be a Flying Dutchman! (2016)

- Loving Languages, A lesson from history: Languages in 17th century New Netherland (2024)

- Lukezic, C. & McCarthy, J.P. (eds.), The Archaeology of New Netherland. A World Built on Trade; Lucas, M.T. & Traudt, K., A Mid-Seventeenth-Century Drinking House in New Netherland (2021)

- Maritiem Portal, Koudumer zeeheld veroverde New York op de Engelsen, nu in Fries Scheepvaart Museum (2018)

- Numan, K. & Pol, van de R., Janssoon van Schaghen, Pieter (1578-1636). Graankoper, raadslid van Alkmaar en lid van de Raad van State, musicus, dichter (2011)

- Otto, P., Peter Stuyvesant (1999)

- Panhuysen, L., De Ware Vrijheid. De levens van Johan en Cornelis de Witt (2015)

- Pennewaard, K., De laatste, verzwegen zeeheld (2018)

- Perlin, R., Language City. The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues (2024)

- Prillevitz, P., Spinoza: een rationalistische mysticus (2015)

- Pye, M., The Edge of the World (2014)

- Romm, R.M., America’s first whaling industry and the whaler yeomen of Cape May 1630-1830 (2010)

- Shomette, D.G. & Haslach, R.D., Raid on America. The Dutch Naval Campaign of 1672-1674 (2013)

- Shorto, R., The Island at the Center of the World. The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony That Shaped America (2004)

- Siefkes, W., Ostfriesische Sagen und sagenhafte Geschichten (1963)

- Sluis, van J., De Academie van Vriesland. Geschiedenis van de Academie en het Athenaeum te Franeker, 1585-1843 (2015)

- Steensen, T., Die Friesen. Menschen am Meer (2020)

- Venema, J., Beverwijck. A Dutch Village on the American Frontier, 1652-1664 (2003)

- Vries, de J., Verzwegen zeeheld. Jacob Benckes (1637-1677) en zijn wereld (2018)

- Vries, de J., Waar is Robinson Crusoe gebleven? (2018)

- Vries, de J., Wat hebben Jacob Benckes en Robinson Crusoe gemeen? (2020)

- Wiarda, H.J., The Dutch Diaspora. The Netherlands and Its Settlements in Africa, Asia, and the Americas (2007)

- Wiersma, J.P., Friese Mythen en Sagen (1973)

- Wijdeven, van de I., Nederland en de VS: Natuurlijke bondgenoten (2010)

- Zijlstra, H., Grafsteen moeder Pieter Stuyvesant ontdekt (2010)

- Zimmerman, J.C., Poëzy 1827-1874 van E.J. Potgieter (1890)

fascinating article, many thanks! One small typo:

“On Broadway 240th St, you can find the only surviving house on Manhattan Island ” in fact it is on the corner of Broadway and 204th street

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks twice!!

LikeLike