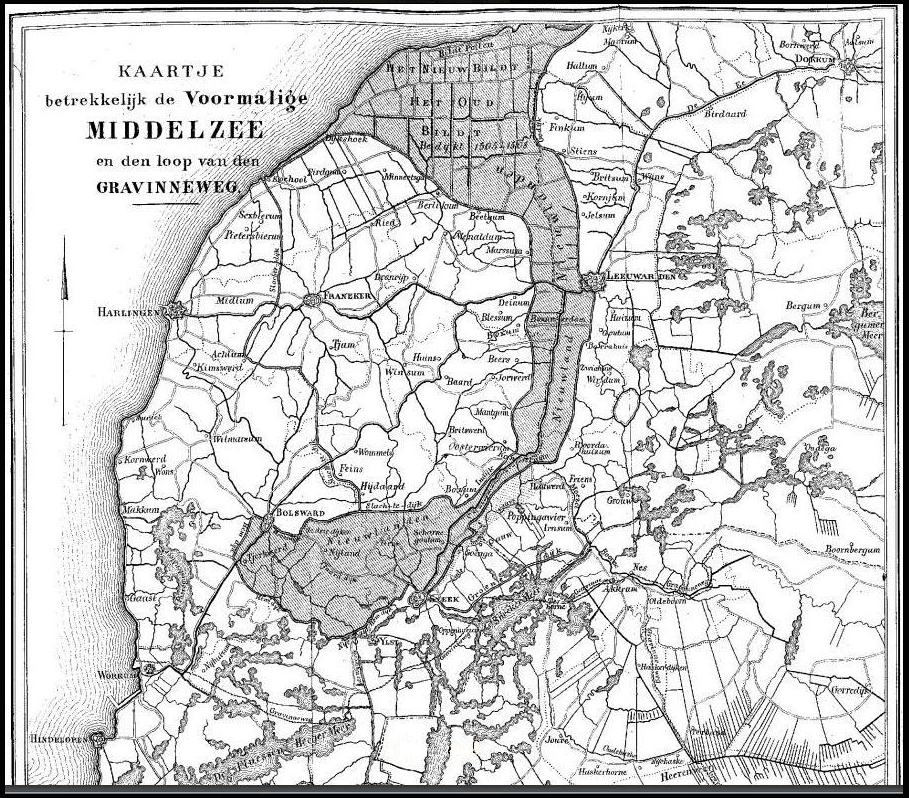

This is the story of the land reclaimed from the former Middelzee — a shallow inland sea that once split the present-day province of Friesland in two, separating the ancient pagus Westrachia (modern district Westergo) from pagus Austrachia (modern district Oostergo). The name Middelzee literally means ‘middle sea.’ Closing this watery rift took centuries. Through a succession of smaller and larger embankments — continuing into the early seventeenth century — new land was steadily won from this inland sea. Once the salt had leached away, migrants from the west and south of the country poured in to make a living on the reclaimed ground. The relevant, mind-bending, and still hotly debated question remains: did these pioneers, settlers, and migrants actually integrate into Frisian society?

An Inland Sea Neutralized

Although the Roman officer and writer Plinius or Pliny the Elder (AD 24–75) already expressed pity for the ‘barbarian’ tribes of the far north — on account of their miserably wet and cold living conditions (see our blog post Shipwrecked People of the Salt Marshes for his exact words) — it was in fact the third and fourth centuries that brought truly tumultuous climatic change. During this period much of the tidal marshland in the terp region (a terp being an artificial dwelling mound) along the Wadden Sea area became uninhabitable. The inhabitants withdrew and resettled elsewhere, producing a habitation gap throughout much of the fifth century.

Note that the habitation gap is occasionally contested — mainly in debates among Frisians and Frisian scholars — because accepting such a gap implies a break with the original Iron Age Frisians. For some, this seems to trigger a kind of phantom pain over the idea of a ‘younger’ Frisian family tree. To rub salt further into that wound, some historians who defend the existence of the gap even refer to this empty interval as:

The time you only could hear the seagulls cry.

The Roman era was also the period in which the Middelzee took shape, when this shallow sea became the new estuary of the small River Boorne — Boarn in the Mid Frisian language. For this reason the inland sea appears in eighth-century sources under the names Bordine, Bordne, or Bordena. The River Boorne itself is known by two additional names: Âlddjip (‘old deep’) and Keningsdjip (‘king’s deep’). The label king indicates that it was a public waterway, not private property — comparable to the herenwegen (‘lords roads’) in, for example, the region of Kennemerland in the province of Noord Holland. The river’s origins go back more than 10,000 years.

For more on this slow-flowing river and its inland sea, as well as on the catastrophic battle of King Poppo — the last known Frisian military leader — against the expansionist Franks at the River Boorne in the first half of the eighth century, see our blog post The Boarn Supremacy.

The inland sea Bordine — the precursor of the Middelzee — holds additional historical significance. It was on its shores, between the pagi (‘territories’) of Westergo and Oostergo, that the already in his own time prominent Anglo-Saxon cleric, Archbishop Saint Boniface, met his death in the summer of 735. It was here — not in the town of Dokkum, nor in that of Dunkirk in the region of Flanders, as is sometimes bizarrely claimed — that Boniface made camp and was attacked and killed (or attempted to be?). Because the shores of the Bordine were extensive and no further historical data survive, the exact crime scene cannot be pinpointed. All of the above follows the near-contemporary account by Willibald of Mainz, written in the second half of the eighth century, describing the life of Saint Boniface.

In the natural world nothing is sustainable and nothing is durable. Toward the end of the first millennium the sea once again pressed into the treeless salt marshes, threatening to ruin the living conditions there. The Christmas Flood of 838 inundated large parts of Frisia and killed several thousand people — a disaster that may be seen as the prelude to a new, aggressive era of the sea. This time, however, the Frisians chose stubbornly to hold their wet ground rather than to emigrate, as their forebears had done in the fourth century.

See our blog post Out of Averting the Inevitable an Unruly Community Was Born about the history of fighting the wild sea and how it shaped the identity of the coastal people.

Geef ons heden ons dagelijks brood, en af en toe een watersnood

saying of Dutch water engineers

Give us this day our daily bread, and now and then a great flood.

The essence of the above adage among Dutch water engineers is that a major flood is the kind of event that periodically forces innovation and progress. Indeed, around the year 1000, Frisians and monastic communities began constructing circular, elevated dykes to protect the land. Step by step they reclaimed ground that had previously been surrendered to the sea. They created an early showcase for the world of what serious land reclamation entails. And it was not only the taming of the inland sea Bordine; throughout Frisia — especially in the region of Westergo — delta works avant la lettre were being executed at the same time. See also our blog post The Mother of All Dykes for more on this water-management effort in the Westergo region specifically.

In the High Middle Ages, Ostfriesen (‘East Frisians’) would migrate to the islands and coast of what is now the region of Nordfriesland, to export their skills of reclaiming land to this area just south of the Danish border. See our blog post Burn Beacon Burn. A Coastal Inferno — Nordfriesland about this medieval migration wave.

To summarize: the Frisians began moving more earth, day after day, than the sea could. Hence the well-known adage Deus mare, Friso litora fecit — ‘God created the sea, the Frisian the coast.’ The saying is frequently misquoted or reassigned to other nations. Success, after all, attracts many fathers, while failure is an orphan.

After another catastrophic flood — the Saint Lucia’s Flood of 1287 — which killed an estimated 50,000 to 80,000 people along the southern North Sea coast and hit Friesland especially hard, a dyke was constructed between the village of Beetgum in the region of Westergo and the village of Britsum in the region of Oostergo. With this enclosure dyke, the reclamation of the Bordine inland sea was roughly halfway complete by around 1300.

North of this dyke, however, a vast stretch of intertidal marsh remained. This area, called Bil, still had to be reclaimed. Reclaiming — or killing — Bil would be the apotheosis of taming the Bordine, later known as the Middelzee. An apotheosis that, incidentally, took even longer to complete than its namesake Hollywood sequel Kill Bill by Quentin Tarantino.

Wild Bil

On 11 August 1398, Lord Arent of Egmond from the province of Holland also acquired lordship over both the Wadden Sea island of Ameland and “een wtlant, gheheten Bil, dat aengewhorpen is buten dycs ende ghelegen is tusschen Meynaertsga ende Sinte Mariengaerde.” In plain English: a tidal marshland called Bil, which has formed outside the dykes and lies between the village of Minnertsga and Saint Mariengaarde. Saint Mariengaarde was the former abbey near the village of Hallum.

Thus, the silted-up clay — the tidal marshland in the last remaining mouth of the former Bordine inland sea — was named Bil. Today the area is known as ’t Bildt, a compound of the Dutch words bil and land. The name echoes that of the Danish town Billund, home of Legoland, but this might be coincidence.

The Dutch word bil is related to bol and to the English and German words ball and Ball: all evoke something rounded and raised above its surroundings — fitting for an elevated marsh ridge. Likewise, on the Wadden Sea island of Juist in the region of Ostfriesland, a former house stead situated on tidal marshland was also called Domäne Bill.

In modern Dutch bil means ‘buttock’. But that is beside the point — and best forgotten that we mentioned it at all.

A century after Bil had been granted to the nobleman Arent of Egmond, funds were raised to pull Bil from the firm grip of the sea. By then it was not only an engineering showcase, but also a clear business case. In 1505, an enclosure dyke more than 14 kilometres long was built between Dijkshoek in the west and Hallumerhoek in the east, securing over 5,000 hectares of fertile salt marsh. The dyke still exists and is known as the Oudebildtdijk — literally ‘old Bildt dyke’. The work was likely completed within just a few years and was, by any standard, an unprecedented feat in the history of global water management.

In 1600, a second dyke — about 13 kilometres long — was built north of the Oudebildtdijk, running from the area of De Westhoek in the west to the village of Nieuwe Bildtzijl in the east. This reclaimed nearly 2,000 hectares of fresh green land from the sea. That dyke, too, still stands and is known as the Nieuwebildtdijk — literally ‘new Bildt dyke’. Indeed, the naming of dykes and villages may not win awards for creativity, but the work itself was impeccably organised and highly functional.

In many respects, the entire enterprise from 1505 onward was exceptionally well-organised and rational. The allotment of land and farms, the straight canals and ditches, the sluices, the siting of villages — all were laid out symmetrically and according to plan. The reclaimed polder of ‘t Oude Bildt became a model for later polders in the Netherlands and abroad. Among its successors was the UNESCO-listed Beemster polder in the province of Noord Holland, created slightly later in 1612 and designed in the same spirit of geometric, rational planning.

Why the Beemster polder is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and not the true original, the polder of ’t Bildt, we have not the faintest idea. Perhaps it is simply because the Beemster lies closer to the capital Amsterdam. Or perhaps it is yet another illustration of the Frisians’ chronic inability to receive credit for their achievements. See more about the lack of these assertive skills with Frisians in our blog post History Is Written by the Victors — A Story of the Credits.

Tamers of Wild Bil

Who were the people of this last frontier? Who tamed Wild Bill? They were not all Uma Thurmans — though Umma is indeed a traditional female first name in the region of Ostfriesland. Nor were they exclusively Frisian workers. No, they were cowboys drawn from across the Netherlands, migrating to the newly fertile northern lands, particularly from the islands of the provinces of Zuid Holland and Zeeland. These early labourers settled — and they stayed.

Let’s return to the central question of this blog post: did these immigrants integrate into local society or not? The answer, of course, depends on how one defines ‘integration.’ Before you get frustrated or throw up your hands at this seemingly bureaucratic hedge, give us a moment to explain.

If economic mobility and participation are your benchmarks for migrant integration, then yes — they did integrate. But it was not easy. The working class, so to speak, was exploited to the maximum by the Frisian and Saxon landowners of the ’t Bildt polder. Farmers and especially landowners profited enormously from the fertile crops, while paying their workers meagre wages. This led not only to extreme poverty among labourers throughout the nineteenth century, but also to the highest levels of secularization in the Netherlands at the time — in a sense following in the footsteps of the heathen and ungodly Frisian mob that centuries earlier had killed Saint Boniface in roughly the same area. Anyway, in terms of integration, at least economically, the migrants fully participated in the local economy — and continue to do so today.

Oh, and one more point: one of the most famous painters of the Dutch Republic, Rembrandt van Rijn, married Saskia van Uylenburgh in the church of the village of Sint Annaparochie in 1634. Saskia was a wealthy young woman from the region of ’t Bildt. Well, if that isn’t integration, we don’t know what is!

Note that not much has changed when it comes to the treatment of low-skilled labour migrants. See the annual report 2021 of the Netherlands’ Labour Inspectorate.

However, if you define integration primarily as adopting the local language and embracing prevailing cultural values, the answer is decidedly no. To this day, the Bildtkers — residents of ’t Bildt — speak a unique creole that is neither Frisian nor Dutch. On top of that, the region retains its almost ‘heathen’ and early secular character. Indeed, the Bildtkers even advocate for official recognition of their creole language — an arguably opposite approach to integration, creating a distinct group language and seeking formal status for it. Try this today in one of the western European countries.

It is also unclear whether Bildtkers would pass the Dutch integration exams required of immigrants today. Yet, in practice, they seem to navigate life quite successfully alongside the rest of the Netherlands’ population.

Therefore, we leave the somewhat fuzzy verdict of whether the Bildtkers are ‘integrated’ or ‘not integrated’ to the reader’s judgment. To be clear, of course, this is not meant as a generalization about contemporary debates on integration and migration.

Note 1 — The father of Saskia and Rembrandt’s father-in-law, Rombertus van Uylenburgh, who was mayor of the town of Leeuwarden, was present at scene of the crime when William of Orange was murdered in the town of Leiden in the year 1584. William of Orange is considered the founding father of the Dutch Republic. See our blog post The Abbey of Egmond and the Rise of the Gerulfings to learn more.

Note 2 — If you want to learn more about the history of ‘t Bildt, now incorporated with other municipalities into the new municipality Waadhoeke, please visit the cultural historic house annex church annex art gallery Aerden Plaats in the beautiful village of Oude Bildtzijl, a name that translates as ‘old Bildt sluice’.

The Oudebildtdijk, with its seemingly endless stretch of former working-class cottages — numbered from 1 to 1229. In the 1970s, it became a magnet for urban migrants from the Netherlands’ cities, including a significant number of artists, drawn by its open landscape and affordable dwellings. Along the dyke you will still find modest art galleries and old cafés nestled side by side. Simultaneously, however, more affluent buyers from outside the province are moving in, acquiring the tiny houses and replacing them with sleek modern architecture.

Note 3 — The Frisia Coast Trail passes through the region of ‘t Bildt. When you enter the tidal marshlands before the dykes at the Wadden Sea side, you will have a chance to get an impression of how Bil looked like before it was reclaimed in the sixteenth century. Even have a feel how it walked like!

Suggested music

- Bacalov, L., The Grand Duel (1972)

Further reading

- Everhardus, K., Een wtlant, gheheten Bil (2025)

- Ferwerda, L., Een uytland gheheten Bil, 1398-2005. De geskidenis fan de gemeente ‘t Bildt (2005)

- Keizer, S., Geschiedenis van ‘t Bildt: Romeinen in Billând? (2020)

- Looijenga, A. & Popkema, A. & Slofstra, B. (transl.), Een meelijwekkend volk. Vreemden over Friezen van de oudheid tot de kerstening (2017)

- Louman, J.P.A., Fries Waterstaatbestuur. Een geschiedenis van de waterbeheersing in Friesland vanaf het midden van de achttiende eeuw tot omstreeks 1970 (2007)

- Schroor, M., Van Middelzee tot Bildt. Landaanwinning in Fryslân in de Middeleeuwen en de vroegmoderne tijd (2000)

- Tuuk, van der L. (ed.), Bonifatius in Dorestad. De evangeliebrenger van de Lage Landen – 716 (2016)