The North Sea coast has always been a dangerous place — and writing about its dialects, languages, and speech communities is no less perilous. Miss a subtlety and your reputation is finished. Too many tongues at once is, as Genesis 11:1–9 warns, even contrary to the will of the gods. To make this Eton mess of speech at least somewhat digestible, we will confine ourselves to the regions covered by the Frisia Coast Trail: from north-western Flanders in Belgium to south-western Jutland in Denmark — and everything in between.

From south to north, the official languages of the four countries you will be hiking through are:

- In Belgium the three official languages are Dutch, French, and German.

- In the Netherlands, the two official languages are Dutch and Frisian, that is, Mid Frisian, also called Westerlauwersk Frysk. The Low Saxon language, also called West Low German or Nedersaksisch, spoken in the northeast and east of the country, is recognized as a regional language but has no official status.

- In Germany, there is one official language, namely German. The official minority languages of Germany are Danish, Frisian (that is, North Frisian or Nordfriesisch, and East Frisian, also called Saterland Frisian or Ostfriesisch), Romani, and Sorbian (both Upper and Lower Sorbian). The West Low German language, also called Westnedderdüütsch, is spoken in the northwest of Germany and forms, together with the West Low German speakers in the east of the Netherlands, one linguistic community.

- In Denmark, like in Germany, there is one official language, namely Danish. The three official minority language are German, Faroese, and Greenlandic.

1. Low Franconian & Low Saxon languages

1.1. Low Franconian

Walking stages 1–3 of the Frisia Coast Trail — from the River Zwin to the River IJ — you cross two countries: Belgium and the Netherlands. All three stages lie within the Low Franconian language area.

Low Franconian has several dialects spoken on three continents. The principal variants are Afrikaans (spoken in the countries of Namibia and South Africa), Brabantic, Flemish (both East and West Flemish), Hollandic, Limburgian, South Guelderish (also called Clevian), and Zeelandic. Flemish, Hollandic, and Suriname-Dutch together form the official language Dutch. The Dutch language has an official status on Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, and in Belgium, the Netherlands, South Africa, and Suriname. Note that Limburgian is also considered a variant of High German, which depends on what the distinctive feature is selected in the definition of language.

The specific Low Franconian dialects you will encounter when hiking these first three stages of the Frisia Coast Trail are Brabantic or Brabants), West Flemish or West-Vlaams, Hollandic or Hollands, and Zeelandic or Zeeuws. The boundary between West Flemish and Zeelandic is marked by the River East-Scheldt in the province of Zeeland in the southwest of the Netherlands.

One linguistic anomaly you will encounter on stage 3 is Westfriesland, a region in the province of Noord Holland in the Netherlands. Here a creole-like vernacular is spoken — a mixture of Hollandic Low Franconian and Old Frisian. This is Westfries, not to be confused with the Mid Frisian language — also called Westerlauwersk Frysk — spoken in the province of Friesland. Commit this distinction to memory. It saves lives!

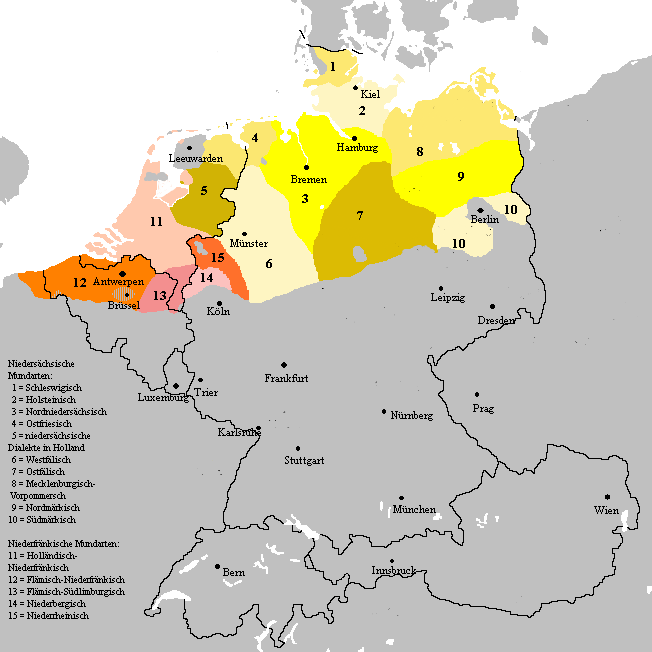

1.2. Low Saxon

With stage 5 of the Frisia Coast Trail you enter Low Saxon territory. Crossing the tiny River Lauwers marks this large linguistic shift. During stages 5 and 6 — between the River Lauwers and the River Jade — you walk first through the province of Groningen in the Netherlands and then through the region of Ostfriesland (East Frisia) in Germany. The Low Saxon speech in both regions is known as Gronings-Oostfreesk. It differs from other Low Saxon varieties due to the strong influence of Old Frisian, which was the language spoken here until the late High Middle Ages. Naturally, Gronings and Oostfreesk also diverge from one another, each shaped by its respective lingua franca: Dutch in Groningen, German in Ostfriesland.

During stage 7, between the River Jade and the River Eider, you still walkabout in the Low-Saxon-language territory. The dialect variants of Low Saxon spoken here are Northern Low Saxon and Holsteinisch. Again, the lingua franca is German.

Stage 8, between the River Eider and the River Vidå, where the North-Frisian language still is spoken modestly, too (see further below under 2), is where the Low Saxon speech Schleswigsch is spoken. In the border area with Denmark, the Danish language is also spoken, and this is one of the official minority language of Germany. About 0,06 percent of the German population speaks the Danish language.

When crossing the border between Germany and Denmark at the start of stage 9 of the trail, you are still within the Schleswigsch Low Saxon language area, although the majority will speak the Danish language or the Jutlandic speech (see further below under 3).

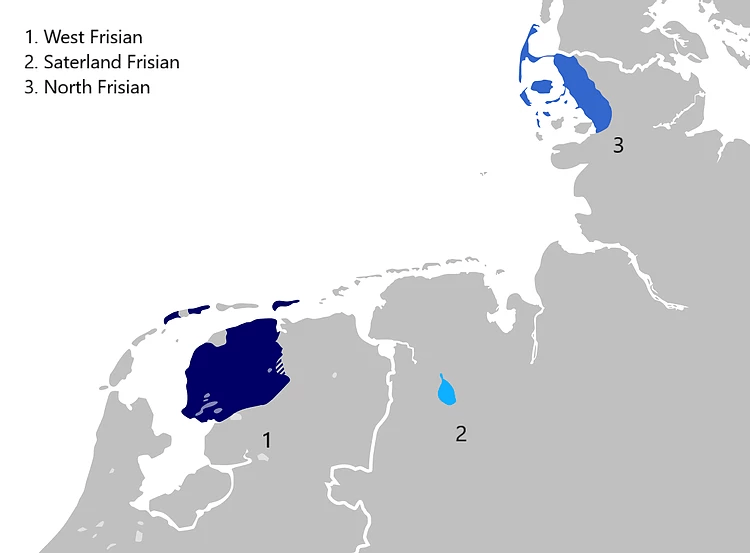

2. Frisian language

Hiking stages 4 – 8 of the Frisia Coast Trail, so between the River Vlie and the River Vidå, you will be walking in areas where the Frisian language is (also) spoken. These are respectively the Frisian dialects Mid Frisian or Westerlauwersk Frysk, and North Frisian or Nordfriisk. There is also a very little patch of East Frisian left in Germany, namely: Sater Frisian or Seeltersk.

2.1. Mid Frisian

Mid Frisian is spoken between the Lake IJssel, or IJsselmeer, and the River Lauwers in the Netherlands and, therefore, locally often referred to as Westerlauwersk Frysk, meaning ‘Frisian west of Lauwers’. Within the Mid Frisian speech several subdialects are being distinguished. The main relevant dialects are Clay-Frisian or Klaaifrysk, Northern-Edge Frisian or Noordhoeks, Southwestern-Edge Frisian or Zuidwesthoeks, and Wood Frisian or Wâldfrysk. These four dialects are quite interchangeable and offer no problem for speakers to understand each other. There is also only one official writing of Mid Frisian in the province of Friesland. All this contrary to the subdialects of North Frisian (see further below under 2.3). Here some words with comparison:

- jûn (mf) – evening (en) – avond (ne) – Abend (de) – aften (da)

- moarne (mf) – morning (en) – ochtend (ne) – Morgen (de) – morgen (da)

- tsjerke (mf) – church (en) – kerk (ne) – Kirche (de) – kirke (da)

- wiet (mf) – wet (en) – nat (ne) – nass (de) – våd (da)

- wetter (mf) – water (en) – water (ne) – Wasser (de) – vand (da)

On the Wadden Sea islands of Schiermonnikoog and Terschelling different dialects of Mid Frisian are spoken. Below some examples:

- English: I – you – you – he / she / it – we – you – they

- Mid Frisian: ik – do – jo – hy / hja & sy / it – wy – jimme – sy

- Schiermonnikoog: ik – dò – ji – hi / jò / et – wy – jimme – jà

Also, the Mid Frisian subdialect of the little town of Hindeloopen in the southwest of the province of Friesland is a different dialect, among other because Old Frisian words have been preserved better due to geographical and social isolation, in combination with a stable population. It became a ‘secret language’ for maritime traders from Hindeloopen, who traded with Scandinavia, the British Isles and the Baltics. That itself might have been extra help for the survival of the Old Frisian language. Other Mid Frisians have a hard time to understand even a bit of Hindeloopen-Frisian, also called Hylpers. Below some examples:

- bòn (hy) – child (en) – bern (mf) – kind (ne) – Kind (de) – barn (da)

- jitte (hy) – yet (en) – noch (mf) – nog (ne) – noch (de) – endnu (da)

- jo (hy) – she (en) – hja/sy (mf) – zij (ne) – Sie (de) – de (da)

- lik (hy) – little (en) – lyts (mf) – klein (ne) – klein (de) – lille (da)

- tòk (hy) – fat (en) – tsjok (mf) – dik/vet (ne) – fett (de) – tyk (da)

There are two non-Frisian language anomalies you will come across when hiking stage 4 in the province of Friesland. The first is the ‘creole’ speech Bildts in the north of the province. This is a mixture of the Frisian and Low Franconian languages. It is spoken in the former Middelzee (‘middle sea’) reclaimed-land area since the beginning of the sixteenth century. Besides a different speech, people here are mostly Catholic instead of being Protestant, what is generally the case in the north of the Netherlands (and Germany). Find here a dictionary of Bildts. The second anomaly is spoken in the southeast of the province of Friesland, namely Stellingwarfs. This is a Low Saxon dialect strongly influenced by the Mid Frisian language.

2.2. East Frisian

Sater Frisian, als called Saterland Frisian or Seeltersk, is spoken in the northwest of Germany in only four villages, viz. Strücklingen (Strukelje), Ramsloh (Roomelse), Sedelsberg (Seedelsbierich), and Scharrel (Schäddel). To avoid disappointment, in the town of Friesoythe, just south of the village of Scharrel, no East Frisian is spoken — neither in the town of Friesenheim near the city of Strasbourg in France, nor in the town of Friesach in Austria, by the way. The Frisia Coast Trail does not pass through these four little villages, but real language freaks can make a detour. Good look with finding someone who still speaks Seeltersk!

Sater Frisian is the last remnant of the East Frisian language which was spoken both in the province of Groningen, that is, the region of Ommelanden, in the Netherlands, and in the whole region of Ostfriesland in Germany until around the fifteenth century. You will hike through the province of Groningen during stage 5, and the region of Ostfriesland during stage 6. It is where the original Frisian language has been replaced by the Low Saxon language, that is, Gronings-Oostfreesk, as said earlier (paragraph 1.2).

The reason Sater Frisian survived, albeit standing on its last legs, has to do with being an ‘island’ within the impenetrable peat area. Their geographical isolation was complemented with social isolation since these villages stayed Catholic during the Reformation. Additionally, maybe also because it became a secret language in trade, comparable with the village of Hindeloopen speech, as described earlier. It is sad, but Sater Frisian is at the brink of extinction. Only a few hundred to a thousand speakers tops are only left (anno 2015). According to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger severely endangered. So, it might justify the detour when you are in the hood. Go quick!

- köäre (sf) – karre (mf) – to choose (en) – wählen (de) – vælge (da) – kiezen (ne)

- speegel (sf) – spegel (mf) – mirror (en) – Spiegel (de)- spejl (da) – spiegel (ne)

- moanske (sf) – minsk (mf) – man/human (en) – Mensch (de) – mand (da) – mens (ne)

- dai (sf) – dei (mf) – day (en) – Tag (de) – dag (da) – dag (ne)

- juun (sf) – tsjin (mf) – against (en) – gegen (de) – mod (da) – tegen (ne)

- tjuusterch (sf) – tjuster (mf) – dark (en) – dunkel (de) – mørk (da) – donker (ne)

Find here a dictionary of Sater Frisian.

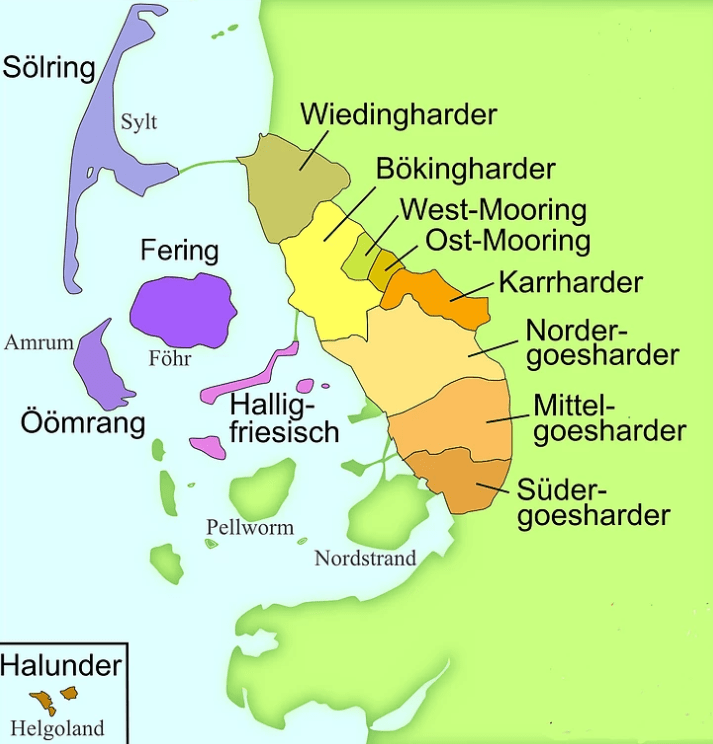

2.3. North Frisian

Hiking stage 8 you will enter Landkreis ‘district’ Nordfriesland, and thus the area where the North Frisian language is spoken. The North Frisian language deserves some additional attention for its complex and even more fragmented situation.

There are two main groups distinguished within this dialect of North Frisian, namely Island North Frisian and Mainland North Frisian. But that is not all. Within these two main groups, many more sub-dialects are spoken. And to be clear, speakers of these sub-dialects cannot understand each other (easy).

Not visible on the map, the dialect Fering, or Ferring, spoken on the island of Föhr, has three sub-dialects: Westland Fering, Southern-Fering, and Eastland Fering. Similar fragmentation is the case on the island of Sylt. The local Frisian dialect Söl’ring is spoken on the middle and southern part of the island. The northern part of the island called List, is Danish speaking. The Norderstrand Frisian spoken on the islands of Pellworm, Nordstrand, and Nordstrandischmoor died in AD 1634. Rungholt Frisian died in AD 1362 when nearly the whole island was swallowed by the sea. See our blog post How a Town Drowned Overnight. The Case of Rungholt.

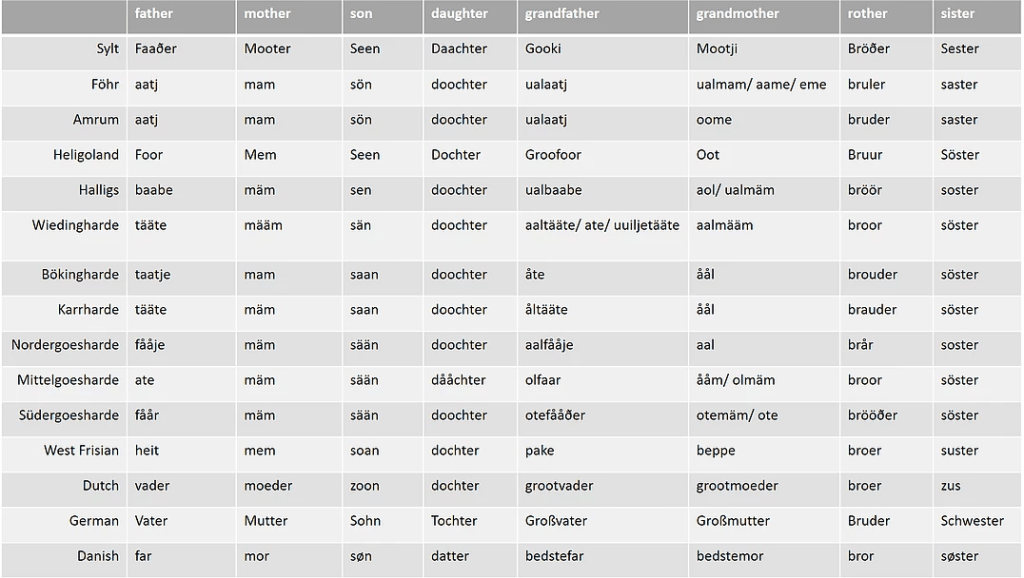

If you take all the existing different North Frisian speeches together, including Heligolandic, also called Halunder, spoken on the island of Heligoland at the North Sea, you still have a staggering fifteen different dialects within the North Frisian language branch. This within an area of just around 2,500 sq km. Let’s give the reader an idea about all the differences:

Three North Frisian speeches and Mid Frisian in a sentence:

- ”She stands at the door”

- Bökingharde: Jü stoont bai e döör.

- Föhr/Fering: Hat stäänt bi a dör.

- Sylt/Söl’ring: Jü staant bi Düür.

- Mid Frisian: Hja stiet by de doar.

All North Frisian variants are at the brink of extinction. No zoos and no breeding programs possible to revitalize the language. Goesharde and Karrharde Frisian have stopped being a spoken language, although some speakers left. In total an estimated maximum of 10,000 people speak one of the variants of the North Frisian language, and thus — according to UNESCO — severely endangered (anno 2015). The fact the North Frisian speeches are very different from each other does not help its survival.

For a dictonary of the Heligolandic or Halunder speech, check here.

3. Danish language

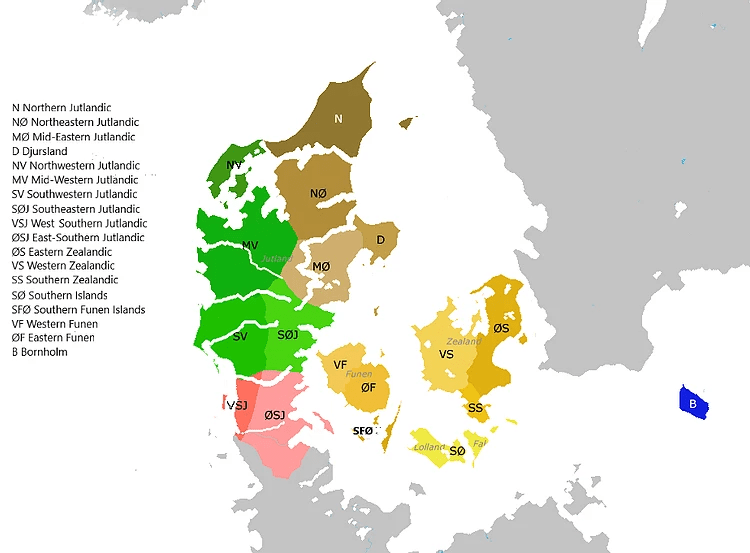

The single Danish dialect you will encounter when hiking the — final — stage 9 of the Frisia Coast Trail is West Southern Jutlandic. Though, you might also encounter German speaking Danes (see further below)

Patchwork in a bottleneck — Linguistically the border area between Denmark and Germany is interesting. Several languages meet here, namely (Southern) Jutlandic, North Frisian (in many dialects) and Schleswigsch Low Saxon, and, of course, the linga francas Danish and German. That are three different families packed together. An area where cultures have met, and where the border between Denmark and Germany bounced up and down for centuries, with the River Eider for long being the median.

The (later to become) duchies Schleswig and Holstein were already an apple of discord between the Franks and the Danes in the Early Middle Ages. After several wars in the nineteenth century, Schleswig was ceded to Prussia in AD 1866. In the aftermath of the Great War and after a referendum in 1920, the people of North Schleswig chose to become part of Denmark. This marks the border as it is today. As a result there is a German minority living in Denmark, and Danish minority living in Germany. The latter specifically in and around the town of Flensburg. Between 15,000 – 20,000 Germans live in southern Denmark of which around 8,000 speak either German or Schleswigsch Low Saxon.

The North Frisians flipped sides during these wars as well. With the separation of North Schleswig from Germany in 1920, the outermost north-western part of the region of Nordfriesland was ceded to Denmark. There are still schools in the southwest of Denmark teaching the North Frisian language.