If you want to track down who killed the whale, the Frisia Coast Trail region is the place to start. Stop people on the streets along this southern North Sea littoral and ask whether they know anything, and you will likely hear: “I hear nothing, I see nothing, I know nothing.” Politicians and officials — say, in The Hague — will lament that they have no recollection of the affair. Better call them all Ishmael. In this blog post, we set out the unvarnished truth: how the peoples living on the coast between the ports of Amsterdam and Hamburg — and up to the Wadden Sea islands of Föhr and Sylt near Denmark — practically exterminated Arctic whale populations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. So take out a pen and paper, and get ready to draft a lawsuit for redress and compensation.

This is a history of the classic whaling in the Arctic fishing grounds that existed between circa 1610 and 1860, commonly known as Grönlandfahrt or Groenlandvaart ‘Greenland navigation’ in the waters east of Greenland, and Davi(d)straatvaart ‘Davis Strait navigation’ in the waters west of Greenland. A whaling industry based in the North Sea coastal zone of the Netherlands and Germany.

Commercial whaling in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, which expanded from the late eighteenth century onward, is not the focus of this blog post. That industry was centred in a very different coastal world — New England in the United States — with its famously busy whaling ports such as Mystic on the Long Island Sound, the now ultra-chic island of Nantucket, and the Cape Cod peninsula. It was an industry led by Americans and immortalised by Herman Melville in Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, published in 1851. Nor does this post concern itself with modern whaling — the era of factory ships that began after the Second World War.

1. But Why?

Before we begin, it helps to understand why the peoples of the southern North Sea coast began harpooning and butchering whales — and other cute-looking, chubby marine mammals — in the Arctic in the first place. The reason was fat. Blubber. From blubber one produced whale oil, better known along the southern North Sea as traan, Tran, or troon, depending on the local speech. The blubber of whales, or of any other fat mammal, was boiled down in large copper cauldrons. After cooling it through several baths of cold water, clear train oil would rise to the surface. The best quality was achieved when the blubber was rendered immediately after the kill. For that reason, whale oil was at first produced on various Arctic islands themselves.

From the mid-seventeenth century onward, however, the blubber increasingly had to be shipped home in barrels and rendered in the patria (‘homeland’) instead — a change in practice we will explain later in this post. Two types of blubber were stored separately: vet (‘fat’) and foul-smelling kreng — impure fat and guts. Incidentally, kreng is still a common mild insult in the Dutch language; if you add vals, meaning ‘vicious,’ to kreng it becomes noticeably less mild.

Oils were indispensable across many industries: in ropewalks, in processing textiles and wool, as lubricants for machinery, and as fuel for lighting — indeed, the greased lightnin’ of the 1970s. In the sixteenth century, prices of vegetable oils rose sharply as Europe’s population boomed. Agriculture shifted to grain production, creating a shortage of oil-seeds. A similar shortage of oils after the Second World War would again drive a renewed wave of commercial whaling.

Another product derived from whales — though not as lucrative as train oil — was baleen. These baleen plates are the keratin bristles in a whale’s mouth used to filter krill. The material is flexible and was turned into all manner of goods: tobacco boxes, umbrella ribs, knife handles. Fashion made baleen especially profitable: it stiffened corsets and, later, the voluminous crinoline dresses.

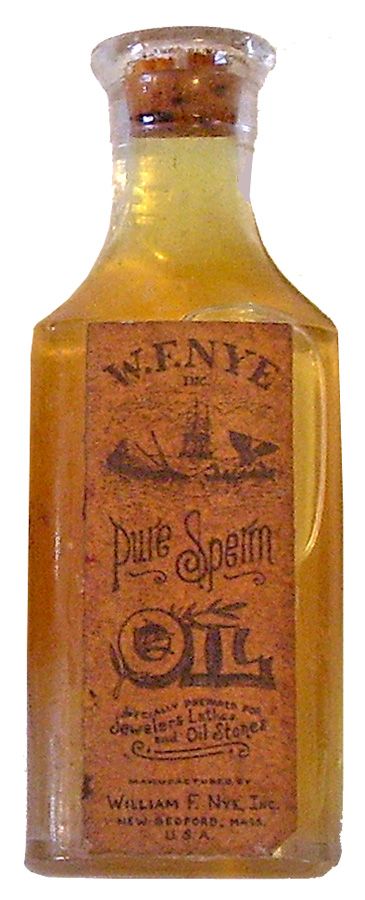

seventeenth-century bottle whale oil and fan, and eighteenth-century bottle sperm oil

Whale bone itself yielded an expensive lubricant known as charnel oil, knekelolie in the Dutch language, used among other things for medicinal purposes. And the bones as such were repurposed too: for fences, paving, even gravestones. When you holiday on one of the Wadden Sea islands of Germany or the Netherlands, just try not to trip over a piece of whale bone. You won’t succeed.

Species hunted at were the grey whale (Eschrichtius robustus) and the North Atlantic right whale (Balaene mysticetus). The latter is also known as the bowhead whale or, in the Dutch language, the noordkaper or groenlandse walvis. One whale yielded about 12,000 liters of train oil (Doedens & Mulder 2024). The right whale is thought to be the longest-living mammal on the planet, estimated to reach 200 years of age, but there are different theories on this. The right whale got its name because it was simply the ‘right’ whale to catch: it swam slowly, was pretty big and heavy, had a very thick layer of blubber, and, most importantly, it did not sink to the sea floor after taking its last breath, due to all its body fat. Many other whale species sink when dead, and at that time, no ropes existed that were strong enough to haul such a dead weight from the blue depths.

At the start of the commercial whaling era, right whales carried a blubber layer of roughly forty to sixty centimetres. Intensive hunting rapidly depressed populations, and with it the average size and fat yield per animal. In the 1760s the average yield was still forty to fifty barrels of vet (‘fat’) per whale; by the 1790s that had collapsed to ten to twenty-five barrels (Bruijn 2016). Around the Spitsbergen archipelago the effect was most visible: decades of over-exploitation had pushed the stock toward younger, leaner whales. West Greenland waters held fatter animals for longer (Baars-Visser et al 2022). By the close of the nineteenth century, the North Atlantic right whale was on the brink of extinction. The North Atlantic grey whale was gone. Full stop.

To warm you up for this icy long-read, we begin with the chilling testimony of a Frisian who spent days wandering stark naked across the frozen, barren wastes of Greenland. Although most recorded encounters between European seafarers and the Inuit of Greenland were amicable, this one was anything but welcoming.

On the Run Stark Naked on Greenland — In 1777, a year remembered as a disaster year, fourteen ships were wrecked in the Arctic waters west of Greenland after a violent August storm: seven from Hamburg and seven from the Dutch Republic. In total, 300 men died that season. Some sailors from the wrecked vessels managed to reach the shores of Greenland, where they encountered the Inuit. One of them was Reinier Hylkes, from the village of Warnt in the province of Friesland. He had sailed on the ship De Hopende Visser — ‘the hopeful fisherman’.

The ‘wilden’ (wildlings) — as the account calls them — brought the surviving whalers to their settlement, where they were given fish, seal meat, and scurvy-grass (also known as salaat or lepelblad). The men were divided between two tents, one large and one small. Hylkes was placed in the large tent with thirty-seven others. They remained there for two weeks, until nineteen men departed in boats they had acquired from the Inuit in the meantime. The others had nothing left of value with which to purchase a vessel.

Those who stayed behind soon sensed a change in atmosphere. Food grew scarce, and they were assigned chores. When relatives of the Inuit arrived, the sailors were made to sing for them and were rewarded with some raw seal meat. Illness was common among the already-weakened men. If someone fell sick, the Inuit would drag him outside and leave him to die in the cold. A new phase followed: men were taken outside one after another, regardless of illness — never to return. The Inuit would sometimes come back laughing and mimicking the last cries they had heard: “Jan, Pieter, Aarjen — oh God, oh God!” These had been the final words of men in mortal terror.

This continued until only Hylkes and four others were still alive. It was now February. That month the Inuit set off northward by boat. After a few days of travel, it emerged that yet another shipmate — likely one who had been placed in the smaller tent — had survived. The joy of reunion was brief: before Hylkes’ eyes, the man was clubbed to death.

Soon after, Hylkes was stripped of his clothes and left naked on the beach. He was told he would be killed the next day. That night he escaped. For three days he wandered, stark naked, along the rocky coast. Then he spotted a tent. The Inuit he met there were friendly; they gave him clothing and food. Later they brought him to a Danish trader. The trader also confronted the group responsible for the killings, but there was nothing he could do. They were too numerous, and any action would have been dangerous for the Europeans. The only outcome was that Hylkes’ clothes were returned.

Now watch the Taxes Chainsaw Massacre movies again.

Another group of whalers fared better that season. Among them was the crew of the Anna, commanded by Jeldert Jansz Groot from the Wadden Sea island of Schiermonnikoog. His nine-year-old son was with him — a decision that, at the time, seems to have raised no eyebrows. They did not experience the horrors described above. Jeldert Jansz reached Frederikshåb on Greenland and, in May of the following year (1778), succeeded in travelling on to Bergen in Norway. From there he returned to the Netherlands. Remarkably, by 1779 he was back at sea, hunting whales again (De Vries 2024).

Another sailor shipwrecked in the disaster year of 1777 was Hidde Dirks Kat (1747–1824), a Frisian from the Wadden Sea island of Ameland. On 30 September, his ship was crushed by pack ice and icebergs during a heavy swell that followed days of severe northeast storm. After an astonishing eleven days adrift on ice floes in open sea — without shelter and with only the scantest supply of food — the survivors reached Statenhoek, the southernmost point of Greenland, known today as Cape Farewell or Nunap Isua in Greenlandic.

Of the seventy-eight men, only eighteen made it to land. Some drowned, some froze to death, and some were left behind in despair because they were too weak to go on. After further wandering along the coast, Kat and the survivors reached an Inuit settlement at Frederikshåb — present-day Paamiut. They were received kindly by the inhabitants. Kat was deeply impressed by them; he even writes that it felt warmer there than at home. The most unpleasant thing he experienced under their care, he notes, was being required to wash himself with human urine — a barrel of collected urine stood inside the house. As for food, his diet consisted mainly of seal, fox, and crow. In 1778, Kat returned to his own damp and windswept island in the Wadden Sea.

Whalers were not spared from cannibalism either. In 1717, the ship of commander Cornelis Sjoukesz of the Wadden Sea island of Terschelling was wrecked near Statenhoek on Spitsbergen. Many of the crew drowned in the storm. The men who reached shore lost nearly all of the provisions they had tried to save. After five weeks of hardship, only three were still alive when rescue finally came — and they had survived only by consuming the corpse of a fellow crew member (Doedens & Mulder 2024).

2. The Run Up to Whaling

The far north was no unknown world to merchants of the Dutch Republic. For centuries they had traded with Norway, Finnmark, and the White Sea region in timber, furs, and hemp. Between 1578 and 1583 the Republic maintained a trading post at the mouth of the Dvina in the Tsardom of Russia; it was later relocated to Novo Kholmogory, where the Dutch eternal rivals — the English — were also present. That settlement would later be known as Arkhangelsk, named after the nearby monastery. From this comes the term Archangelvaart, the Arkhangelsk navigation.

One of the early explorers of the Arctic was Olivier Brunel (also spelled Bruyneel) from the town of Leuven in the region of Flanders. In 1584 he ventured into the region — and tragically, it was to be his last voyage. He drowned in 1585 near the mouth of the Pechora. Brunel is regarded as the founder of the Arkhangelsk navigation. Incidentally, the name survives in modern sailing culture: ‘Team Brunel,’ led by Dutch sailor Bouwe Bekking, is a major competitor in the Volvo Ocean Race — but that is another story altogether.

By the late sixteenth century the English and the Dutch had become consumed by the idea of a sea route to Asia through the Arctic — the fabled Northeast Passage. Such a route promised to be shorter and therefore cheaper. The overland Silk Road to Asia was slow and perilous, and thus expensive. A northern maritime route would also free the English and Dutch from constant harassment by the Portuguese, Spanish, and French on the traditional sea lanes, and would bypass waters and harbours rife with pirates, privateers, and Barbary or Salé corsairs. Of course, the Northeast Passage would only become feasible four centuries later, after human civilization had warmed the earth enough to melt the ice.

From England, the Elizabethan navigators — a group of seafarers, explorers, cartographers, and privateers, also known as the Sea Dogs — set course from the docks at Wapping on the River Thames to the Arctic in 1553 to find the Northeast Passage (Duncan 2022). It was an undertaking financed by London merchants. Their fleet of three ships was scattered by a storm. The ship of Hugh Willoughby, the captain-general of the fleet, became disoriented and could not find the others. They must have become trapped by the ice and were forced to winter in the Arctic, probably on the Kola Peninsula near the mouth of the River Varzina. No one survived.

The Republic launched three expeditions in search of the Northeast Passage. In 1594 two ships set out: one under the command of the West Frisian Cornelis Nay of Enkhuizen, the other under the Frisian Willem Barentsz of the Wadden Sea island of Terschelling. The Frisian navigator Pieter Dirksz Keyser from the city of Emden from the region of Ostfriesland also joined the venture.

Nay and his crew reached the Kara Strait, south of Novaya Zemlya. There they also took what is considered the first whale in Dutch Arctic waters — on 14 July 1594. Jan Huygens van Linschoten, who witnessed the event, recorded the ‘first blood’ in his travelogue. The whale was a young animal. While the men stripped the blubber and hacked the carcass to pieces on the shore, the mother hovered offshore, lifting her body high from the water as if to watch the butchery, the Dexter-like massacre — a grim prelude to the centuries of slaughter that would follow. It was not a day of celebration, although it happened on quatorze juillet.

One of the two whalebone jawbones that Van Linschoten brought back from the Arctic still hangs from the ceiling of the old town hall in Haarlem.

A year later, in 1595, a fleet of seven ships under command of Nay gave it another, second, try. Barentsz was also one of the captains. Of course, no passage to Asia was found.

Third time lucky — in 1596 the stubborn Willem Barentsz mounted yet another attempt to find the Northeast Passage. This expedition sailed with only two ships: one commanded by Jacob van Heemskerck and the other by Jan Cornelisz de Rijp, with Barentsz acting as overall leader. The venture was initiated by none other than the Land’s Advocate, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt.

It was during this voyage that Barentsz discovered the archipelago of Spitsbergen ‘peak mountains’ and Beereneiland ‘bears island’. His ship got stuck in the ice at the archipelago of Novaya Zemlya. ‘Zoo vast als Haarlem‘, as the expression was when a ship got beset ‘stuck’ in the ice. Referring to the long siege of the town of Haarlem by the Spanish in the years 1572-1573 (Baars-Visser 2022). Finally the ship was crushed. Barentsz and his crew had to stay. For ten dark months they had to defy the harsh Arctic winter. They managed to survive in a house they had built from driftwood and wood of the ship. A house they named ‘t Behouden Huys ‘the preserving house’. With a sloop they had constructed, they rowed 2,500 kilometers back to the mainland once the sea was ice free the next year. On their way back, Barentsz died on 20 June 1597. Besides Barentsz, another four did not survive the sloop journey back (Walda 1996).

It was on this voyage that Barentsz discovered the archipelago of Spitsbergen — ‘jagged mountains’ — and Beereneiland ‘bears island.’ His ship eventually became trapped in the ice at Novaya Zemlya: “zoo vast als Haarlem” (‘as tight as Haarlem’), as they used to say when a ship was beset. An expression referring to the long siege of the city of Haarlem by the Spanish in 1572–73 (Baars-Visser 2022). In the end the ship was crushed. Barentsz and his men were forced to defy the cold winter there. For ten dark months they endured the brutal Arctic season, surviving in a house they built from driftwood and salvaged timbers of the wreck, which they named ’t Behouden Huys — ‘the preserved house.’

When the sea opened the following year, they set off in a small boat they had constructed and rowed some 2,500 kilometres back toward the mainland. Barentsz died en route, on 20 June 1597, and four others perished during the open-boat return as well (Walda 1996).

The States General had offered a reward of 25,000 guilders for finding the Northeast Passage. Had he survived, one may wonder whether Barentsz would have considered it worth the ordeal. For the record: the ship under Jacob van Heemskerck escaped the Arctic winter and made it safely back home.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the English — spurred on by the Muscovy Company — also set their sights on the Northeast Passage. The Muscovy Company, also known as the Russia Company and founded in 1551, held a monopoly on English–Russian trade and already possessed a whaling charter by 1557. In the years 1603, 1604, 1605, 1607, and 1610 the company financed a series of expeditions to the Arctic in search of the passage.

The one of 1607 was led by the famous explorer Henry Hudson. Shortly after this expedition, Hudson was hired by Dutch merchants of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie VOC to discover a Northeast Passage. In the year 1609, sailing under the Dutch flag, he did not discover a passage but something completely else: the River Hudson and the island of Manhattan. No idea how Hudson ended up all the way in west given his assignment. Anyway, it is here where the New Netherland colony and the town of New Amsterdam, future New York City, soon would be founded. See our blog post History Is Written by the Victors — A Story of the Credits for more about this piece of Dutch-Frisian world-changing history.

One engaging anecdote comes from the English expedition of 1610, led by Jonas Pool. As Pool’s ship passed the waters of the Spitsbergen archipelago, the sea was thick with whales. There were so many of them that they bumped against the anchor chains and even struck the rudder. One can imagine the scene.

As for Spitsbergen, the Norwegians annexed the archipelago in the twentieth century — on the classic argument that the Vikings had already discovered everything worth discovering in the northern hemisphere, and that therefore every grain of sand, pebble, and rock up there was theirs by right, that included Greenland. One cannot deny that Norwegians think big. To make their claim visible, they also renamed Spitsbergen ‘Svalbard,’ meaning ‘cold coast.’ Even so, Barentsz’s name Spitsbergen for the entire archipelago has remained the dominant one to this day — at least some consolation for Barentsz’s efforts.

The Republic made no territorial claims to the rocks, islands, or lands discovered by Barentsz. Merchants and investors at home were interested only in profiting from the surrounding waters. In all other respects, they adhered to Hugo Grotius’ principle of mare liberum — ‘the free sea.’ Nor did the Republic claim Beereneiland (now Bjørnøya) or the island of Jan Mayen, both likewise discovered by Dutch seafarers. The latter still bears the name of its discoverer, Jan Jacobsz Mayen, from the village of Schellinkhout in the region of Westfriesland, who landed there in 1614.

The latter still bears the name of its discoverer, Jan Jacobsz Mayen, from the village of Schellinkhout in the region of Westfriesland, who landed there in 1614. The Dutch doctrine of mare liberum in the Arctic spared them from later discussions involving Denmark and the United States over Greenland. Denmark had received Greenland from Norway in 1814, and in 1946 President Truman offered to buy the land for 100,000 USD, but this proposal did not lead to an agreement. Since 2019, President Trump has made clear that he too wants it, one way or the other (Ewing 2019, Yeomans 2025).

As said, all of these islands have since been claimed by the king of Norway on the basis of the Viking refrain: “Vikings must have been there, therefore it is ours.” Whether the Norwegians consulted the Inuit before advancing their claims is unknown. And if one follows that line of reasoning, the Irish might have an even older claim than the Vikings: Irish monks were already sailing to remote islands in the tradition of peregrinatio dei in the sixth century. Who knows — perhaps one day Ireland will file a case at the Peace Palace in The Hague arguing that Greenland, Bjørnøya, Spitsbergen, and Jan Mayen are in fact Irish territory.

3. Basque Tutors

In 1611, Arctic whaling really took off. Demand for oil was high and prices followed. Thanks to earlier voyages, both the Republic and England had by then charted the Arctic well. The Muscovy Company fitted out two ships for the blubber hunt. A year later, in 1612, Dutch investors sent out a ship under Willem Cornelisz van Muyden. Because neither country had any real experience in hunting, killing, cutting, and processing these giants, they hired Basque seamen — especially harpooners and speksnijders (‘whale-cutters’). This coastal people had been whaling for generations and became the Master Yodas of large-scale commercial whaling in the Arctic for the Dutch, Frisians, Germans, and — to a lesser extent — the English and Danes in the early modern period.

The Basques were hunting whales already by the mid-eleventh century — and probably earlier, though the evidence for earlier dates is circumstantial. The chase was primarily for meat. Salted ‘fish’ — whales were classified as fish at the time — filled an economic niche created by Catholic dietary rules: no meat on Fridays, nor on the countless saints’ days. Not unlike why fish-and-chips shops are popular today with Muslim youth as an easy halal snack.

Medieval Basque whaling did not yet reach the Arctic; it took place in their own waters, the Bay of Biscay, where the North Atlantic right whale migrated north. In the Euskara language the Basques call it sarda, ‘schooling whale.’ They also hunted the grey whale, otta sotta. One wonders how the pious would fare at Heaven’s gate when questioned by Saint Peter: they could honestly say they had never eaten meat on Fridays or feast days — only ‘fish.’ And one cannot blame the Basques for this theological loophole: they, too, sincerely believed whales were fish.

Along the Biscayan coast the Basques built stone watchtowers — vigías — to scan the sea for whales. Once whales were sighted, small open boats, called chalupas in Euskara language, were launched in pursuit. The French called them chaloupes, the English shallops, the German Schaluppe. The Dutch word sloep clearly comes from the same root, and from that the English sloop (Chamson 2014). A chalupa was crewed by five oarsmen, a harpooner, and a steersman.

The harpoon, tied to the boat by a rope, was thrown by hand. The whale was then tired out. Many whales overheat under prolonged exertion; their blubber is too thick to shed excessive body heat fast enough. Once the animal was exhausted, the whalers closed in again and killed it with a lance — a smooth blade without barbs, called a lens in Dutch — aiming for lungs or heart. Basque whaling in the Bay of Biscay peaked around the mid-sixteenth century and declined soon after.

Besides chalupa, another Dutch/English borrowing from Basque is harpoon. It derives from the Basque verb apoi, meaning ‘to grab’ (Doedens & Mulder 2024).

Whale Rodeo in the Arctic Arena — Harpooner Jacob Dieukes from Assendelft in the province of Holland became the first recorded successful whale rodeo rider in history. In 1660, he threw his harpoon into a whale — and then fell overboard. The harpoon lines tangled around his lower body, binding him to the terrified, thrashing animal. The whale bolted, dragging Dieukes through the freezing Arctic waters. The men in the sloop struggled to keep up, but the whale was too fast. Three times it dove into the icy depths, each plunge testing Dieukes’ endurance as he held his breath like a rider on a wild horse. Finally, after the third dive, the harpoon slipped free. Dieukes grabbed his knife, cut himself loose. He was hauled back aboard, quickly clothed — before resuming the hunt. Well, Daryl Mills, chew on that!

The scene echoes Herman Melville’s Mob — Dick or The Whale, where the harpooner Fedallah is similarly tied to the white sperm whale. Fedallah, however, never survived the ordeal. Only Ishmael, the storyteller, the designated survivor, did. Whether Melville drew inspiration from Dieukes’ historic ride remains unknown.

It was in the first quarter of the sixteenth century that the Basques began hunting whales in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence — known to them as la gran baya — along the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The Strait of Belle Isle, in particular, became an important Basque whaling ground. At Red Bay, archaeological excavations have uncovered rendering stations, including the remains of tryworks.

Research suggests that although cod fishing was initially their main objective, whale hunting served as a secondary or fallback activity for the Basques between 1520 and 1530. From around 1540 onward, they began organizing dedicated whaling expeditions to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, employing the same coastal hunting methods they had long used in the Bay of Biscay — a practice that dated back to the Middle Ages.

For a long time, the Basques managed to keep the locations of their cod fishing and whaling grounds secret. To this day, it remains uncertain when exactly they began fishing for cod in Canadian waters — was it before or after Christopher Columbus ‘discovered’ America in 1492? That question still lingers. In a way, it is not so different from today: ask a sport angler where they caught that trophy pikeperch or carp, and you are unlikely to get a straight answer.

Whales were still hunted by the Basques primarily for their meat, which was salted, but also for their oil. Train oil — or grasa de ballena — was used for lighting lamps and, when mixed with tar, for caulking ships.

The so-called Terra Nova industry reached its peak between 1560 and 1570. Each summer during this period, around twenty ships — carrying a total of some 2,000 men — sailed from the Basque Country to the cold Canadian shores. By 1620, however, this activity had come to an end. Scholars still debate the reasons for its decline. It may have resulted from overhunting, which led to a sharp reduction in right whale populations; in just fifty years, an estimated 20,000 whales were killed. Others point to external factors within Castile, such as wars, forced recruitment for the Armada, heavy taxation, and a fall in the price of train oil. The latter explanation seems more convincing, as commercial whaling soon revived elsewhere and once again became a profitable enterprise.

The preceding account illustrates how crucial Basque expertise was to the early Dutch and English whaling enterprises. The newcomers relied heavily on Basque experience and skill, and Basque sailors knew their worth — hiring them came at a high price. Between 1612 and 1639, more than a quarter of all whaling crews consisted of Basque officers. It is therefore unsurprising that the Dutch sought to acquire the necessary knowledge themselves as quickly as possible in order to reduce costs.

From 1640 to 1700, the Basque share of the crews declined sharply to just a few percent. Their places were increasingly taken by Frisians from the province of Friesland and from the region of Ostfriesland, as well as by seamen from the Frisian Wadden Sea islands — Ameland, Borkum, Terschelling, Texel, and Vlieland — and from most of the islands and Halligen of the the region of Nordfriesland.

Especially ‘the march of the Troonbook‘ into the whaling branch was significant, as we will see further below in this blog post, when discussing the massive participation and representation of the Nordfriesen in the Arctic whale hunt. Troonbook, by the way, is a North Frisian word and translates as ‘train-oil beacon,’ referring to the penetrating smell of sailors when they returned home from whaling after many months at sea. To be more precise, the smell was a mixture of train oil, overcooked peas, and old sweat.

The same was true for the Wadden Sea island of Borkum. More than one hundred commanders came from there, including Roelof Gerritz Meyer (1712–1798), who sailed forty-seven times to the Arctic and hunted 311 whales (Dirks 2023).

One Basque sailor deserves special mention: Jean Vrolicq, also known to the Dutch as Jan or Johannes Vrolyk. Claimed to have discovered Disco Island and the rich whaling grounds of Disco Bay in the year 1629. The French Cardinal Duke of Richelieu, convinced by Vrolicq’s promising reports, granted him a charter for whaling north of 60 degrees latitude. Commander Cornelis Pietersz Ys from the Wadden Sea island of Vlieland, however, was less impressed by this cardinal privilege. In 1634, he confiscated five of Vrolicq’s hunting sloops and bluntly ordered the French Basque to seek his fortunes — and misfortunes — elsewhere (Doedens & Houter 2022).

Vrolicq’s claim to have discovered Disco Island, however, is undeserved. The true credit belongs to the Norseman Erik Thorvaldsson, better known as Erik the Red, who lived in the tenth century. The Viking settlers of Greenland used the island as a summer hunting ground, which they called Norðrsetur. Or perhaps, one might wonder, were the Irish monks there even earlier?

Anyway, the presence of the Dutch along the coasts of Greenland is clearly reflected in the many toponyms they left behind: Walvis Eilanden (‘whale islands’), Honden Eilanden (‘dog islands’), Vlakke Groene Eilanden (‘flat green islands’), Fortuyn Baai (‘fortune bay’), and Liefde Baai (‘love bay’) — some of which are still in use today (Baars-Visser et al 2022). What exactly took place at Liefde Baai, however, will be revealed further below.

4. Monopoly Whaling

The initial heart of commercial whaling lay with the wealthy merchants of the city of Amsterdam and the regions north of it — particularly the region of Zaan and the villages of Graft and De Rijp on the former island of Schermer, and to a lesser extent the regions of Waterland and Westfriesland, including De Zijpe. From the former island of Huisduinen, many commandeurs (whaling commanders) also originated, about whom we will say more later. All these areas are located in what is now the province of Noord Holland.

More broadly, by the end of the sixteenth century, the three coastal provinces of the Dutch Republic — Zeeland, Holland and West-Friesland, and Friesland — had together built the largest merchant fleet the world had ever seen up to that time.

Besides a long-standing seafaring tradition dating back to the Early Middle Ages (see our blog post Porcupines Bore U.S. Bucks: the Birth of Economic Liberalism), this coastal strip achieved its maritime dominance through innovations in shipbuilding. During the Dutch Republic, shipyards were able to produce standardized, and therefore cheaper, vessels, which helped the region dominate North Sea freight. A key example was the three-masted fluit ship — also called flute, fluyt, or fly-boat — developed in the Westfrisian town of Hoorn. Its impact on shipping was comparable to the black-painted Ford Model T rolling off the assembly lines in Detroit from 1908 onward. As Henry Ford famously said: “Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black.”

With the introduction of cheap fluit ships, the Dutch Republic became a leader particularly in the maritime trade of grain, wood, and salt. Beyond the assembly-line-style production, these vessels featured several innovations: large cargo capacity, no armament, and the ability to operate with a small crew. Living and sleeping quarters were shared by the entire crew, regardless of rank — a rarity at the time. In a way, one could even see it as a precursor to today’s much-loved concept of hot-desking or flex office spaces. All of these features reduced costs and increased profits.

By around 1600, the Dutch Republic had unmistakably become the hub of global trade. Bustling Amsterdam overflowed with investors and capital hungry for new ventures. Reports from the Arctic promised rich rewards, and soon these financiers turned their attention to the icy north, to the prospects of commercial whaling.

The beginning of whaling in 1612 quickly led to conflicts among ships from different countries operating in the waters around the Spitsbergen archipelago. In addition, to strengthen their position against the English Muscovy Company, several Dutch merchants petitioned the States General of the Republic for an octroy (charter). In 1614, a three-year charter was granted, which stated:

van Nova Sembla tot Fretum Davids toe, daeronder begrepen Spitsbergen, Beereneylant, Groenlandt ende andere eylanden, die onder de voorsz. Limieten souden mogen gevonden worden

octroy of the Noordt Compagnie

from Novaya Zemlya to Davis Strait, including Spitsbergen (i.e. modern Svalbard), Beereneylant (i.e. modern Bjørnøya), Greenland and other islands, which may be found within the aforementioned limitations

The charter was renewed in 1617, 1622, 1623, and for a final time in 1634. By 1642, the charter expired, and from that point onward, whaling became a fully open, private enterprise.

The 1614 charter marked the founding of the Noordsche Compagnie (‘northern company’), somewhat analogous to the earlier VOC and the West-Indische Compagnie (WIC). Initially, the Noordsche Compagnie consisted of five sections, the so-called kamers (‘chambers’), representing the cities of Amsterdam, Delft, Enkhuizen, Hoorn, and Rotterdam. In 1617, a separate, smaller company was established following the discovery of Jan Mayen Island a few years earlier. In 1623, this smaller company was merged into the larger Noordsche Compagnie.

Later, in 1635, the kamer of the port town of Harlingen in the province of Friesland was added to the Compagnie. This followed a serious conflict between the States General of the Republic in The Hague and the States of Friesland, after the latter had been denied participation by the Noordsche Compagnie. A year earlier, the province of Friesland had created leverage in this dispute with Holland by unilaterally granting a charter to Hilbrand Dircksz, burgomaster of Harlingen, and Wijbe Jansz, burgomaster of Stavoren — both receiving their own kamer (Doedens & Houter 2022).

Before long, the States General in The Hague reversed course. The persistent, pain-in-the-neck Frisians were finally admitted, and a kamer of Harlingen was officially added to the Noordsche Compagnie. It was probably located at the north end of the Zuiderhaven docks (Otten 2022).

The Noordsche Compagnie established whaling stations on Spitsbergen, Jan Mayen Island, and Beereneiland (‘bear island’). In the northwest of the Spitsbergen archipelago, three factorijen — small seasonal factories or landing stations — were set up. These tryworks-cum-settlements included Smeerenburg (‘smear town’) on Amsterdam Island, Harlinger Traankokerij (‘Harlingen oil factory’) on Deenseiland, and Zeeuwse Uytkyck (‘Zeeland lookout’) on the northernmost point of the archipelago.

Everything was, in a sense, very republican — united yet independent — as each coastal province — Holland, Friesland, and Zeeland — maintained its own base. The English, meanwhile, concentrated their operations in the southern part of the Spitsbergen archipelago, where they established their own tryworks. Thus, both nations managed to coexist amid the vast and icy expanse of the northern seas.

After some less-equable Basques plundered the company’s storage facilities on Spitsbergen in 1632, the Noordsche Compagnie — never short of bold or inventive ideas — decided to attempt a year-round presence in the Arctic. It proved a disastrous, and perhaps not entirely well-considered, experiment. In 1633, seven men stayed the winter on Jan Mayen Island; none survived. At Smeerenburg on Spitsbergen, however, the overwintering succeeded that same year. The men there managed to find enough scurvy-grass in time to secure the essential vitamin C that kept scurvy at bay: a scurvy-grass a day keeps the doctor away.

The following winter, though, fate turned again: all seven men who attempted to overwinter at Smeerenburg perished miserably. After that, the company laid its Arctic overwintering ambitions to rest for good. Still, as every modern manager likes to tell their team — it is okay to make mistakes, at least you tried.

Besides Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen Island, men also overwintered on Beereneiland. This, however, happened involuntarily — after a shipwreck. The Frisian helmsman Lambert Pietersz Geweldt, from the Wadden Sea island of Vlieland, survived a dreadful winter there, from 3 November 1700 to 16 July 1701. He and his crew slept in an improvised tent, sometimes enduring temperatures close to thirty degrees below freezing. Geweldt and his men survived on a grim diet of foxes, bears, birds, eggs, and walrus. Only in June did they manage to find some scurvy-grass — just in time, as all of them were by then suffering severely from scurvy. In the end, only four of the ten men survived (Doedens & Houter 2022). Indeed, what a way to ring in a new century.

The typical routine of whalers was to set sail in spring and return well after summer. Their route ran from the Wadden Sea island of Texel to the Shetland Islands, and from there onward to the Spitsbergen archipelago, Jan Mayen Island, and Beereneiland . Shetland, by the way, was known to the Dutch as Hitland — a name borrowed from Faroese, in which the islands are called Hetland.

As soon as the ships departed from the Texel anchorage, the so-called vleet (pronounced ‘flate’) or armazoen was distributed among the crew. The armazoen, supplied by the shipowner, consisted of whaling equipment such as harpoons, lances, and countless varieties of whale-cutting knives. Each crew member was responsible for preparing and sharpening their own tools and splicing their own hunting ropes. Everything had to be ready by the time they reached the Arctic seas.

The sloops were also prepared for immediate action. When the command Val! Val! was shouted, all boats — often six in total — had to be manned at once, with six or seven men per sloop. As the sailors used to say, the whale would not wait for them. The Dutch word val literally means ‘to fall’ or ‘to drop.’ If a hunt failed, the whalers would speak of a loose val — a ‘futile fall.’ A typical whaling ship carried around forty-five men, all listed on the monsterrolle (‘muster roll’), which was drawn up by an official known as the waterschout (‘water sheriff’). For comparison, a fluit ship in regular maritime trade required only about fifteen men to operate. Clearly, whaling — with three times the crew — was an intensive and costly enterprise.

Note that on board whaling ships, command was not held by a kapitein (‘captain’) but by a commandeur (‘commander’). The owner of the enterprise was known as the directeur (‘director’) or boekhouder (‘bookkeeper’). In addition to commanding the ship at sea, the commander was also responsible for recruiting his crew. These men were often relatives or trusted acquaintances from the same village or region, supplemented with others from farther afield — sometimes as far away as Germany. Interviews with potential crew members typically took place in the local tavern. If the applicant was hired, he received a small advance known as wijnkoop (‘wine purchase’), meant for buying warm clothing and personal supplies such as tobacco (Baars-Visser et al 2022). And perhaps, who knows, a little wine as well.

From 1719 onward, as the hunting grounds expanded into Davis Strait along Greenland’s west coast, ships set sail westward from Shetland toward Statenhoek, the southernmost tip of Greenland. From there, they continued north into the strait. The entire voyage to these distant hunting grounds took roughly six weeks.

Top 10 dangers for whalers — (1) pack-ice, (2) ice bergs, (3) heavy storms, (4) the hunt itself, (5) scurvy, (6) pirates and privateers (mostly French and Spanish), (7) illnesses, (8) mutiny, (9) Inuit, (10) sea monsters (unverified)

Reliable statistics on the number and proportion of seamen who died are not available. However, the recorded shipwrecks and fatalities indicate that whaling was a considerably safer occupation than sailing with the VOC to the West. In that trade, a mortality rate of around fifty percent was quite common. Of course, those voyages lasted much longer, which also increased the time spent at risk.

From the late 1630s onward, the profits of the Noordsche Compagnie began to decline. The main cause was climate change — yes, even then. As the climate grew warmer, the edge of the pack ice retreated farther north. Since whales feed primarily along the margins of the ice, they now had to be hunted farther out at sea (Hacquebord 2019). Because the Noordsche Compagnie’s charter applied only to the shores of lands and islands — based on Grotius’s earlier concept of mare liberum — the company could no longer profit from its monopoly. Consequently, an increasing number of whaling ships were financed by Dutch entrepreneurs to operate in the open sea: hvalfangst i no man’s land.

The Noordsche Compagnie did petition for a new charter — this time for the entire Arctic — but the States General in The Hague declined the request on principle. As a result, fierce competition arose on the high seas, not only with foreign nations such as the English and French but now also among ships financed by the Dutch themselves. A free market had emerged. Cooperation among the kamers deteriorated, and it became every man for himself.

As mentioned earlier, the company’s charter expired in 1642 and was not renewed. Although the Noordsche Compagnie lost its monopoly, the Amsterdam kamer continued to operate as a commercial enterprise until 1658, and the Harlingen kamer held out a little longer, until 1662.

Whaling was an important source of revenue for the port town of Harlingen. In terms of value, train oil was the most significant export commodity of Harlingen in the mid-seventeenth century. Between 1641 and 1660, at least seven skippers from Harlingen were active in whaling. In the notarial archives of Amsterdam for the period 1640–1664, twenty skippers from Harlingen have been identified (Doedens & Houter 2022).

Given that whales now had to be caught much farther from the islands, dead whales could no longer be dragged to the landing stations for prompt processing into train oil. The distances were simply too great, and the operation too time-consuming. To maximize efficiency and profit, whales had to be processed at sea. Additionally, a dead whale decays rapidly. As a result, the processing stations on the Spitsbergen archipelago were abandoned in the 1650s, the last one closing in 1660. Although whales were thereafter cut at sea, the blubber was not rendered on board, as doing so would have been far too risky — any fire could have destroyed the ship. Instead, the blubber was stored in airtight barrels to be rendered back home.

Dissecting the whale at sea was a very dangerous activity. First, the animal was fixed on the port side of the ship with its tail to the bow. Speksnijders would then cut the whale with long, ultra-sharp knives while standing on the greasy, slippery animal that bobbed on the waves. For this task, the speksnijders received a bonus called ontweigeld, which translates as ‘disembowel money’ (Doedens & Mulder 2024).

In Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick or The Whale (1851), in which the whaling of the late modern period is described, a paragraph is devoted to the speksnijder. Melville explains that the English word specksionier is derived from the Dutch maritime term speksnyder. On board Dutch Arctic whaling ships, the captain — responsible primarily for navigation and overall management of the vessel — did not oversee the hunt itself. That role fell to the specksionier, also called the first harpooner, who directed the hunt and managed all tasks connected to it, including the cutting of the blubber. The skill and performance of the specksionier were therefore of paramount importance to the success of the enterprise.

5. Free Whaling for Everyone

From the late 1630s, whaling had become a booming industry. By 1650, the English Muscovy Company had exited the trade, bankrupt due to deteriorating relations between England and the Tsardom of Russia. England would only modestly re-enter whaling in the second quarter of the eighteenth century. Yet by the mid-eighteenth century, English production had already matched that of the Dutch Republic and would soon surpass it, taking the lead in the industry. The English whaling sector was heavily subsidized by the state — a clear distortion of competition from the Dutch perspective. This support also served a strategic military purpose: sailors employed in whaling effectively functioned as a reserve pool for the British navy. Ensuring the rapid availability of trained sailors for warships was a constant concern for naval powers.

Between 1670 and 1730, Arctic whaling reached its peak. Each season, between 150 and 250 ships were outfitted from the Republic for the hunt, sometimes even as many as 300. Over the course of the eighteenth century, an average of 260 ships sailed to the ice seas each year (Leinenga 2015). Prior to 1642, only 300 to 400 whales were typically caught annually; afterward, the numbers skyrocketed to around 2,000 per year.

The Republic also began whaling across the Atlantic, in their newly established colony of New Netherland. In 1629, the West-Indische Compagnie (WIC, or Dutch West India Company) purchased land in Delaware Bay from the Lenape tribe, partly with the aim of commercial whaling (Romm 2010). On this tract, the settlement of Swaanendael — present-day Lewes — was founded, and it was here that the Dutch first attempted whaling in 1631. The eighty original settlers even sailed to the Americas aboard a ship named De Walvis (‘the whale’) in 1630. Coincidence? Perhaps, but the venture quickly turned disastrous: most settlers were killed by the Lenape shortly after their arrival in 1632, possibly due to a misunderstanding.

The following year, another attempt was made to begin whaling in Delaware Bay, including at Cape May (Degener 2012). However, these settlers lacked both the skills and the high-quality harpoons necessary for effective hunting — no Basques on hand to teach them. While commercial whaling never developed in New Netherland, these early efforts mark the beginning of American whaling history, aside from any possible earlier, undocumented Basque activity.

In addition to the Republic, the free cities of Bremen and, especially, Hamburg along the southern coast of the North Sea also participated in whaling. This followed the expiration of the charter of the Noordsche Compagnie. These cities outfitted roughly sixty ships each season. From the mid-fifteenth century, Bremen and Hamburg claimed the status of Freie Reichsstadt — free imperial cities not subject to any duchy or lord. Their commercial practices were similar to those of the Republic, and strong connections existed between them.

From 1640, Hamburg maintained its own landing station and trywork on the western shores of the Spitsbergen archipelago, known as Hamburg-Bucht, or in the Dutch language, Hamburger Baaytje. Like the Republic, the ‘German’ cities of Bremen and Hamburg favoured the principle of international free maritime trade, in contrast to Denmark, England, and Sweden, which pursued mercantilist, protectionist policies. The term ‘German’ is placed in quotation marks because, in the eighteenth century, there was no unified German state — only a collection of principalities, counties, and (free) cities.

What about the Danes?

Danish whaling began under the leadership of Dutch pioneers. Johan (or Jan) de Villum from the Republic was granted the right to hunt whales in the Arctic in 1614. Four years later, De Villum partnered with the Dane Jens Munk to establish a whaling company. In 1617, another Dutchman, Herman Rosenkrantz from the city of Rotterdam, co-founded a separate Danish whaling venture. Both companies were minor players, each sending a ship to the Spitsbergen archipelago in 1619. The following year, Johan Braem, yet another Dutchman in Denmark, became director of the Greenlandic Company. This enterprise proved unsuccessful and was liquidated in 1652 (Christensen 2021).

After these early Dutch-Danish enterprises, the Danes did not engage in organized whaling until the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Apparently, following considerable deliberation, their king established the Kongelige Grønlandske Handel (KGH, ‘royal Greenlandic trade’) in 1774 — a time when Arctic whaling was already in decline. This royal enterprise purchased eight ships that year and added another eight the following year. Denmark unilaterally declared that its company held a monopoly over Greenland and the Spitsbergen archipelago, including navigation along their coasts. In practice, however, a sweet fleet of sixteen ships was no match for the German free cities, and certainly not for the Republic or England. For comparison, in 1776 the Republic still sent 123 ships to the Arctic, while Hamburg deployed fifty-one.

Interestingly, twelve of the sixteen Danish ships were commanded by Nordfriesen (or North Frisians), seafarers primarily from the Wadden Sea islands of Föhr and Sylt. Much more about the Nordfriesen is discussed further below. The KGH’s operational success was limited. When it ordered harpoons and other equipment in 1776, their quality proved extremely poor. According to the North Frisian commanders, the harpoons broke even when thrown against a thin sheet of glass, rendering them effectively unusable.

The above is not entirely fair to the Danes. There were private persons who were involved with whaling until 1775. Especially, the merchant Jacob Severin who had received the exclusive right to hunt whales for Denmark and their province Norway. Both countries were constitutional united under the Danish monarchy. Severin was in practice viceroy of Greenland for long. But, at the end these privileged individuals were not able to punch themselves a way out of a paper bag when it came to setting up a profitable whaling business.

By the mid-seventeenth century, the fluit ships of the Republic were being adapted for Arctic conditions. Ships were often trapped, or ‘sandwiched,’ by pack ice, which was usually not too dangerous — once the wind shifted, they could free themselves from the firm grip of the ice. The real danger arose when strong winds blew consistently from a single direction, causing immense pressure on the hull; under such conditions, the ice could crush the ship. On average, about four percent of ships were lost each year (Feddersen 1991).

To provide additional protection, the bow and hull of fluit ships were reinforced with a second layer, called verdubbelen (‘to double’). This ijshuid (‘ice skin’) better shielded the vessel from drifting ice and icebergs. Nevertheless, seafarers considered placing a whale carcass between the ship and the pack ice the most effective defence against ice pressure. Ships were also equipped to carry six or seven hunting sloops, enhancing their operational capabilities during the hunt.

At the end of the seventeenth century, a new type of ship was introduced: the bootschiff or bootschip (‘boat-ship’). It featured a robust bow and, compared with the fluit ship, a broader deck. The wider deck was necessary because, from the mid-seventeenth century onward, blubber had to be processed at sea, as explained earlier. Cutting and storing the blubber on board required additional working space on deck. The bootschip became the standard whaling vessel of the eighteenth century. Later, the brig-type ship — known in the Dutch language as brik and in the German language as Brigg — followed.

As whale populations declined in the seas around Spitsbergen, Jan Mayen, and Beereneiland, new happy hunting grounds had to be found. In 1669, the average catch per ship was eight whales; by 1789, it had dropped to just two. Although annual averages fluctuated, the overall trend was clearly downward. To illustrate: 1669 — 8 whales; 1691 — 2.5; 1701 — 5.8; 1728 — 1.1; 1744 — 4; 1762 — 1.5; 1781 — 4.2; 1789 — 2. A voyage was considered profitable if a ship returned with at least four whales (Leinenga 2015). Of course, profitability also depended on current prices for (vegetable) oil and on additional costs, especially if ships sailed as far as the west coast of Greenland, which required higher expenditures for crew wages and provisions.

From 1719 onward, ships from the Republic began whaling west of Greenland, in Davis Strait, often referred to as Davidstraat. Along the west coast of Greenland, two sea currents converge: a warm current flowing southward along the coast, and the cold Labrador Current, entering from northern Baffin Bay. Where these currents meet, plankton flourishes, creating abundant feeding grounds for baleen whales and, consequently, excellent hunting grounds. Whales were generally larger and fatter along the west coast of Greenland than around the Spitsbergen archipelago, reflecting the fact that Spitsbergen populations had already been heavily overhunted. Typically, by early May, Disco Bay in Davis Strait would be ice-free, marking a prime location to begin the hunt. Whalers would then gradually move northward following the seasonal retreat of the ice, with the Davis Strait season concluding in late June.

It was the Frisian seafarer Laurens Feyjes Haan, from the Wadden Sea island of Terschelling, who had been sailing annually to the waters west of Greenland for trade since 1708. Islanders from Terschelling had been bartering with the Inuit of Greenland throughout much of the seventeenth century. In 1719, Haan published a book providing directions for navigating to Davis Strait, and whalers promptly began moving westward.

The Inuit — referred to by the Dutch as wilden (‘wildings’), wildemannen (‘wild men’), or Groenlanders (‘Greenlanders’) — were described in the mid-sixteenth century as a people who ate their fish raw and also enjoyed raw meat and seal fat. Bird eggs were boiled until they turned blue, and fish such as sprat and mullet were cooked as well. Lamps were made using moss and seal oil.

Greenland was, of course, Danish territory, and the Kompagni til Grønlands besejling (‘Greenland navigation company’) conducted trade there. At the same time, many officers on Danish merchant and naval ships in the early modern period were from the Republic. Notable examples include cartographer Joris Carolus and David Urbanis Dannel, who captained ships for the Kompagni in the second quarter of the seventeenth century, sailing regularly between Denmark and Greenland (Christensen 2021).

Because the waters of Davis Strait were much farther from the patria (‘home country’) and voyages took longer, it was, as mentioned, a more costly hunting ground. On average, reaching the west coast of Greenland required six weeks at sea. Ships often sailed along coasts or archipelagos such as Orkney, Shetland, the Faroes, or the Norwegian coast, which also provided opportunities to take on fresh supplies.

6. Origins of Whalers

The whole whaling business had become an efficient and reasonably profitable enterprise by the mid-seventeenth century. It created quite a lot of work — jobs that could not be filled entirely by the hinterlands of the Republic or the city of Hamburg. So, contract workers were brought in. But who were these workers from elsewhere?

A first general observation concerns the broader picture of where seafarers in the Republic’s merchant marine came from. Around 1710, at the height of the Republic’s power, about seventy-five percent of its sailors were from the Republic itself. Of these, roughly forty-seven percent came from the province of Friesland, including the Wadden Sea islands. Of the remaining twenty-five percent who came from abroad, forty-three percent originated from the region of Ostfriesland, including its Wadden Sea islands, and from the Duchy of Schleswig — essentially the area of Nordfriesland.

The overall picture, then, is that during the heyday of the Republic, nearly half of its merchant fleet was of Frisian origin. And considering that the Frisian regions of origin had a much lower population density than the province of Holland, it is clear that the Frisians were still a sea people par excellence. And to think, this does not even take into account the massive inland navigation. When it comes to being a water people, the Frisians could easily shake hands with the Basques — besides shaking hands over having problems with kings, central governments, and being scattered across several countries.

A second general remark about the background of the whalers is that quite a few of them were Anabaptists. The reason for this is simple once you see it. Anabaptists rejected the use of violence, which meant that neither the Admiralties nor the quasi-militaristic merchant fleets of the VOC and WIC were an option for them. Another theoretical option might have been the fisheries, but the crews of the herring busses were recruited exclusively from the local fishing villages — no outsiders accepted, except perhaps someone from a neighbouring village at best.

So, self-employment through private enterprise or, indeed, work in the unarmed whaling industry were credible options for these pacifists, denouncers of violence. A relatively large number of them lived in the province of Friesland, the region of Ostfriesland, and on the Frisian Wadden Sea islands. Think of Menno Simons and the Mennonites, who also originated from this region — a Protestant movement known for its pacifism and simple way of life. Of course, their rejection of violence applied only to other humans — not to the mammals paddling with fins and flippers through the icy seas.

Zakkoek, a Real Treat — The last whaling ship to set sail for the Arctic leaving from Harlingen was the Dirkje Adema, in 1862. Some notes have been preserved about the crew’s diet. One item mentioned is zakkoek — literally ‘sack cake’ or ‘sack cookie.’ The batter was made with brewer’s yeast, and perhaps with raisins. It took many hours to prepare: the mixture was placed in a linen sack and hung au bain-marie from the ceiling of the caboose the day before. Every Wednesday and Sunday, the men were served zakkoek. They loved it!

This dish hails from the northern provinces of the Netherlands and is known by many other names: ketelkoek (‘kettle cake’), Jan in de Zak (‘John in the sack’), Witte Zuster (‘white nurse’), Broeder (‘male nurse’), Blinde Dirk (‘blind Dirk’), Poffert, Boffert, and Trommelkoek (‘lunch-box cake’). It is sometimes served with butter and syrup. We are curious whether other regions along the Wadden Sea coast are familiar with this recipe too — let us know!

Between 1612 and 1639 — spanning the start of commercial whaling to the end of the Noordsche Compagnie — the vast majority of commanders came from the northern part of the province of Holland, particularly from Amsterdam and the surrounding area north of the city. About eighty percent of all commanders originated from Holland, while nearly twenty percent came from the province of Friesland or the southern Frisian Wadden Sea islands. In absolute numbers, that meant twenty-eight Frisian commanders.

Between 1640 and 1665, the share of Frisian commanders increased sharply. The proportion from Holland dropped to about fifty-five percent, while that of the Frisians rose to nearly forty percent — amounting to 385 Frisian commanders in total.

Throughout the seventeenth century, focusing on the Republic, it was the Wadden Sea islanders of Vlieland — and to a lesser extent those of Terschelling — who provided the largest number of commanders. Research into maritime freighting contracts from the period 1640–1664 shows that most commanders, 59 in total, came from the island of Vlieland. The port town of Stavoren on the mainland of the province of Friesland followed with 54, the major city of Amsterdam with a mere 50, and the island of Terschelling with 36 commanders.

Around 1650, an estimated one hundred ships from the island of Vlieland were operating in the Arctic. The reason for the islanders’ strong representation is clear: even before the rise of commercial whaling, the island of Vlieland already possessed a sizable fleet engaged in trade, particularly with the Baltic region. Their vessels — galiots and fluit ships — were versatile, multi-purpose craft (Doedens & Houter 2022).

After 1700, the number of commanders from the Wadden Sea island of Vlieland declined sharply. Many of them had come from the village of Westeynde, at the western end of the island. Westeynde was gradually swallowed by the sea from the second half of the seventeenth century and was finally abandoned in 1736. Many of its inhabitants resettled on the former island of Huisduinen in the north of the province of Holland. By the second half of the seventeenth century, Huisduinen supplied about thirty percent of the commanders, making it the main provider of whaling captains. And why do you think that was?

A similar pattern can be seen with the crews of whalers. Between 1612 and 1639, nearly sixty percent of the crew came from the province of Holland and the region of Westfriesland, primarily from Amsterdam and the area north of the city. About thirty percent came from the Basque Country, while only eight percent hailed from Friesland and the southern Frisian Wadden Sea islands.

This picture changed dramatically in the following decades. Between 1640 and 1700, almost sixty-five percent of the crew came from Holland and Westfriesland. The share of Frisians in the whaling fleet rose to roughly a third, including men from the Frisian Wadden Sea islands. For the first time, Nordfriesen from the Wadden Sea island of Föhr appear in the records. Meanwhile, the expensive Basques had become largely unnecessary, dropping to a mere two percent of all crew.

The composition of whaling crews during this period shows some striking similarities with the northern Arkangelsk trade. In this northern Russian navigation, fifty-five percent of the crew came from the province of Holland and the region of Westfriesland, while thirty-six percent hailed from Friesland, including the southern Frisian Wadden Sea islands.

Over the eighteenth century and into the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the picture becomes even more striking regarding the share of Frisians in whaling crews. Roughly half of the crew came from the northern coast of Germany — especially the regions of Ostfriesland and Nordfriesland, and from the (German-)Frisian Wadden Sea islands — while only about a third came from the Republic itself. Of this third, around eight percent were from the province of Friesland or the Frisian Wadden Sea islands.

As a rough indication, during much of the eighteenth century, Frisians from the various Frisian regions along the Wadden Sea coast accounted for roughly fifty to sixty percent of all whaling crew on ships of the Republic. In this context, the region of Westfriesland, part of the province of Holland since the late thirteenth century, is not counted as a separate Frisian region. So, if you would view it through Frisian-colored glasses, the share of Frisians was even higher.

The Wadden Sea islands also contributed significantly to the number of whaling commanders. Of the 1,250 commanders in the eighteenth century, no fewer than 490 came from the (Frisian) Wadden Sea islands. The main islands were Föhr (Nordfriesland) with 128, Ameland (Friesland) with 121, Terschelling (Friesland) with 88, Texel (Holland) with 75, and Borkum (Ostfriesland) with 65 commanders. The island of Vlieland continued to supply commanders and crew as well, though not nearly as much as in the previous century. Many commanders still came from the northern part of the province of Holland, of course. And again, it is worth remembering that commanders from the former island of Huisduinen in the north of the province of Holland were, in fact, recently resettled islanders from Vlieland.

7. Island Nordfriesen

The first phase of whaling, from 1612 until around 1660, largely passed by the region of Nordfriesland. It was only in the eighteenth century that the number of Nordfriesen seamen serving in the whaling fleet of the Republic began to rise significantly.

Throughout the entire whaling era, the Nordfriesen never outfitted any ships of their own. Even if they had considered it, competition from the free cities of Altona, Amsterdam, Hamburg, Glückstadt, and Bremen would have been far too fierce. And such ventures required businessmen and investors with capital — something Nordfriesland lacked at the time. A modest attempt was made in the town of Husum, but it was short-lived.

Die Inselfriesen als eifrige und tüchtige Wallfischfänger

The Island-Frisians as eager and capable whalers (Chronik der friesisichen Uthlande, 1856)

Relations between the region of Nordfriesland and the Dutch Republic dated back to well before the Nordfriesen entered the whaling industry. From the first half of the seventeenth century, Nordfriesen were active in maritime trade, particularly in the transport of Danish oxen and Scandinavian timber to the Republic. An important harbour for the export of oxen bred in southern Jutland was the town of Ribe. Using their smack ships — also known as smakschepen or smackschiffen — small, flat-bottomed vessels well suited to the shallow waters of the Wadden Sea, they carried out most of this trade. In modest numbers, Nordfriesen also served in the fleets of the VOC and the Admiralties.

Because of the intensive trade in oxen and timber, strong connections developed with the region of Westfriesland — particularly with the towns of Enkhuizen and Hoorn, together with Amsterdam (Christensen 2021). Not only Föhrer, that is, Nordfriesen from the Wadden Sea island of Föhr, took part in this maritime trade, but also men from the island of Nordstrand and from the towns of Husum, Møltønder, and Tønder. Islanders from Oland and Rømø were involved as well.

From around 1660 onward, increasing numbers of Nordfriesen — again mainly from the island of Föhr — settled in Amsterdam. Analyses of the city’s marriage registers clearly show this, as many North Frisian grooms appear in the records. Many Föhrer lived in the neighbourhood known as the Oude Teertuinen (‘old tar gardens’), which is today part of Prins Hendrikkade street. Interestingly, the quay of Prins Hendrikkade was also the mooring place of the daily market ferry connecting Amsterdam with the town of Hindeloopen in the southwest of the province of Friesland (Van Doorn 2021) — yet another link between the Frisians of the north and those of the Republic.

When Nordfriesen enlisted for whaling in the Republic, they were given Dutch personal names free of charge. Apparently, their North Frisian names proved too difficult for the Dutch tongue to handle. Or perhaps it was simply the Dutch conservative streak — the preference for keeping things familiar — that was at play. Here is an impression of how these names were adapted into Dutch:

Arfst—Adriaen; Erk—Dirk; Früd—Frederik; Girre—Gerrit; Hark—Hendrik; Hay—Hendrik; Jap—Jacob; Ketel—Cornelis; Nahmen—Nanning; Ocke—Adriaen; Rörd—Riewert; Sönk—Simon; Tay—Teunis; Tücke—Teunis; Wögen—Willem (Faltings 2011).

This name conversion makes historical research all the more challenging, as it often conceals the true Nordfrisian origins of those listed in the records, like those of marriage registers as mentioned.

The reason why the Nordfriesen began to take part in whaling was that, after the charter of the Noordsche Compagnie was not renewed, the industry became a fully open enterprise within the Republic from 1642 onward. The Republic was the dominant power in North Atlantic whaling, and from that point on, anyone with sufficient means could purchase shares — parten — in a whaling ship. These shares were typically divided into fractions of 1/8, 1/16, 1/32, or 1/64.

Wealthy merchants, shipyards, and investors in the Republic had ample capital to establish new shipping companies or to invest in whaling expeditions. The industry flourished, creating a great demand for skilled maritime labour. This was the opportunity the already well-connected Nordfriesen had been waiting for — and they seized it with full dedication, soon establishing a strong and lasting presence in the whaling trade.

It is sometimes argued that the Nordfriesen entered the whaling trade because France, in 1633, forbade the Basques from serving on the Republic’s whaling ships. In reality, however, this was not the decisive factor. Basque sailors continued to enlist on Dutch whaling ships between 1625 and 1641 — and even as late as 1669 (Hacquebord 1999).

Another explanation often given for the large-scale Nordfrisian involvement in whaling — sometimes mentioned alongside the previous argument — is the catastrophic storm surge of 1634, known as the Burchardi flood. This Grote Mandränke (‘great drowning of men’), as it is still remembered locally, devastated much of the southern North Sea coast and struck the region of Nordfriesland with particular force. Between 8,000 and 15,000 people drowned in a single day. The Hallig-island of Strand was shattered into fragments, leaving behind only a few smaller Halligen. Of its roughly 9,100 inhabitants, about 6,100 perished.

The island of Strand had also served as the granary of Nordfriesland. Its destruction therefore brought not only immense human loss but also widespread poverty. In the wake of this disaster, whaling offered a crucial new means of livelihood — and for many Nordfriesen, a chance at survival.

By 1700, around 3,600 Nordfriesen were at the whaling — most of them from the Wadden Sea islands of Sylt and Föhr, but also from the Hallig-islands and the island of Rømø. Remarkably, among every twenty to thirty Nordfriesen, one served as a commander. The golden age of the Nordfriesen in whaling lasted from roughly 1745 to 1785. During this period, about twenty-five percent of all island Nordfriesen worked at sea on whaling ships. In the peak year of 1762, nearly 1,200 men from the island of Föhr alone set out on whaling expeditions. In practice, this meant that virtually all adult men — except for the elderly — were whalers.

The mid-eighteenth century also marked a turning point: whaling was no longer sustainable. After a century of catching more whales than the natural population could replenish, the balance tipped around 1750. Whale numbers declined sharply, and the once-booming industry ceased to be profitable (Baars-Visser et al 2022).

According to the Chronik der friesischen Uthlande (Hansen 1856), between 1673 and 1713 the Island Frisians supplied the Dutch and German Greenland whaling fleets with a contingent of between 3,000 and 4,000 Matrosen, Speckschneider, Harpunierer, Boots- and Steuermänner — that is, sailors, specksioniers, harpooners, boatmen, and helmsmen — including many commanders, particularly in the Hamburg fleet.

The Nordfriesen were highly valued for their exceptional sailing and navigation skills — so much so that many rose to the very top of the maritime ranks. Numerous Nordfriesen became helmsmen or commanders on ships outfitted in the Republic and in the free city of Hamburg, and later also by the Danes. In 1762 alone, forty-three commanders were Nordfriesen. It is probably no exaggeration to say that without them, the whaling industries of the Republic and Hamburg would not have been able to crew their ships (Holm 2003).

Private Navigation Schools Nordfriesland — The region of Nordfriesland had a unique system for teaching its youth the art of navigation—particularly on the island of Föhr, and later also on Sylt and parts of the mainland. These were private schools, known in the Ferring dialect — a variant of North Frisian language — as Naawigatjuunsskuulen (‘navigation schools’), run from the homes of former sailors who trained young men for a modest fee — typically a shilling per day plus the cost of heating. Instruction usually took place during the winter months and in the evenings.

Thanks to these home schools, local knowledge of piloting, celestial navigation, and mathematics was of an exceptionally high standard. This allowed Nordfriesen to attain positions as helmsmen and commanders on foreign ships, particularly those from the Republic and from the Elbe region. Study books were in either in the Dutch or German language, while the teaching itself was conducted in the North Frisian language. After completing private instruction, students often continued their education at maritime academies in the cities of Copenhagen or Hamburg, where they took official state examinations. The Nordfriesen soon earned a reputation as some of the finest navigators in northern Europe.

This private navigation school system thrived for about two centuries, until it came to an abrupt end in 1864. The cause, as so often, was political. When Prussia conquered the Duchy of Schleswig from Denmark, the region of Nordfriesland became part of Prussia. Three years later, the Naawigatjuunsskuulen were abolished. From then on, aspiring navigators were required to study at state institutions on the mainland — far away, time-consuming, and costly, around 1,000 Marks for nine months of training. It is also possible that the Prussian authorities closed the island schools because they were seen as hotbeds of anti-Prussian sentiment.

The decline of the private navigation schools marked the end of Nordfriesland’s great seafaring tradition. Many Nordfriesen turned to other livelihoods or chose to emigrate, particularly to the United States. In that same year, 1867, island Nordfriesen also became subject to compulsory military service in the Prussian army — a duty from which they had been exempt under Danish rule before. This new obligation likely encouraged even more young men to seek a new life across the Atlantic, especially in the promising cities of New York and California.

Navigation Instruction the Netherlands — In the Netherlands, navigation at sea was traditionally taught by former captains, commanders, and sometimes by (former) mathematics teachers. Already in 1785, a maritime school was founded in Amsterdam — the Kweekschool voor de Zeevaart (‘training school for seafaring’). In the port town of Harlingen, a maritime school was established in 1818, which still exists today as the Maritieme Academie Holland.

Furthermore, during the nineteenth century, four navigation schools operated on the Wadden Sea islands of Texel, Vlieland, Terschelling, and Schiermonnikoog. Of these, only the school on Terschelling survived and continues today as the Maritiem Instituut Willem Barentsz. Other navigation schools existed in Vlissingen, Rotterdam, Den Helder, Groningen, and Delfzijl. In other words, apart from Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Vlissingen, it was the northern Netherlands that hosted most — albeit smaller — navigation schools.

Students in the port town of Harlingen, locally known as zeebaby’s (‘sea babies’), generally came from lower-class families. As in the region of Nordfriesland, instruction mainly took place during the winter months. During the sailing season, men and boys — sometimes as young as thirteen — were expected to work on ships. When winters were mild and the waters remained ice-free, attendance often dropped, as students continued working at sea or in inland shipping.

Relevant Textbooks — One of the most important maritime manuals in the Republic — and also among the Nordfriesen — was the book by Claes (or Klaas) de Vries (1662–1730), titled Schat-kamer ofte konst der stier-lieden (‘treasury or the art of helmsmen’), published in 1702. It remained in use until around 1820. De Vries, a cartographer, mathematician, and maritime expert, was born in Leeuwarden in the province of Friesland. The term schatkamer (‘treasure chamber’) was commonly used for manuscripts containing personal notes on nautical and navigational matters (Bruijn 2016).

Another influential work was Grondbeginselen des stuurmanskunst (‘fundamentals of the art of steerage’), published in 1766 by Pybo Steenstra (1731?–1788), who was born in Franeker, also in Friesland. Two further important navigation manuals were ’t Vergulde licht der zeevaert (‘the gilded light of navigation’) by Claes Hindrickz Gietermaker (1660) and Nieuw en Groote Zee-Spiegel (‘new and great sea mirror’) by Caspar Lootsmans (1680).

Navigation schools in Copenhagen, Hamburg, Christiania (modern Oslo), Porsgrunn, and Danzig also trained their students using these Dutch textbooks, mirrors, and manuals (Christensen 2021).

In early February, the commanders set sail from the region of Nordfriesland to the River Elbe — that is, Hamburg — and to the Republic aboard smack ships to prepare their vessels for the upcoming whaling season. The voyage to the free city of Hamburg took about three days, while the journey to the city of Amsterdam in the Province Holland lasted around seven. A few weeks later, the lower-ranking sailors followed, travelling in convoys of ten to fourteen smack ships.

More than a thousand men from the island of Föhr alone joined the whaling expeditions. Typically, a commander recruited most of his crew from his own village or island. Thus, a commander from Föhr would sail with a crew made up largely of fellow Föhrers; likewise, a commander from the island of Vlieland would choose men from Vlieland — and so on, and so forth.